Shawanda CorbettTo the Fields of Lilac

Now on View

Installation Views

Artwork

Shawanda Corbett works across ceramics, film, performance, and dance often collaborating with her choreographer (and brother) Albert Corbett. Her varied artistic practice attends to the relationship between these mediums. Her ceramic objects, for example, speak deeply to an imagination and intuition enlivened by performance. Moreover, as Corbett’s vessels can be described as either ceramics, cyborg sculptures, performative objects and so on, one’s inability to define them as one or the other speaks to their resistance to fixed categorizations and their alignment with hybridity.

Ahead of her first solo exhibition in the United States at Salon 94 tilted To the Fields of Lilac, Corbett continues her exploration into a ceramic practice rooted in the personal whilst extending to a range of references from cross-cultural and geographic pottery traditions in West Africa, Asia, and back to ancient civilizations. Black feminist writer Toni Morrison’s book Beloved (1987) was a source of inspiration as the author framed racism as a form of “cultural haunting”. “I named the show To the Fields of Lilac to signal a continuation or a further narrative that thinks about what happens beyond ‘Wade in the Water’’, the spiritual originally sung by slaves on their quest for freedom and thinking about how water became a signifier for protection for the enslaved on their road to freedom,” she said recently. “But what does it mean to actually be free? Are we really absolutely free in a capitalist, neoliberal society we find ourselves in today?”

Sixteen vessels of different heights, shapes, leans and glazes—notably, violet hues are prominent in this body of work—form a gathering of sorts in the gallery with titles that express some familiarity in catchphrases such as Do you see what I see”, “Our freedom is not your absolute freedom”, “Stop all that slouching, boy”, “Just the blind leading the blind”, and “The ground beneath us” (all works 2021). Each vessel is inspired by a real person, but rather than calling them by their actual names, they are repositioned anew. Bold, blinging and determined the personages are placed in a stereotype-free space. An ensemble without prejudice or neighborhood borders. The musicality of improvised, transcendental Jazz served as a score of sorts to Corbett’s mark-making on objects’ surfaces (Corbett mentioned in conversation, the one-track, nine-movement album Promises by Floating Points, Pharoah Sanders and The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) looming sonically in her studio as she made these new works).

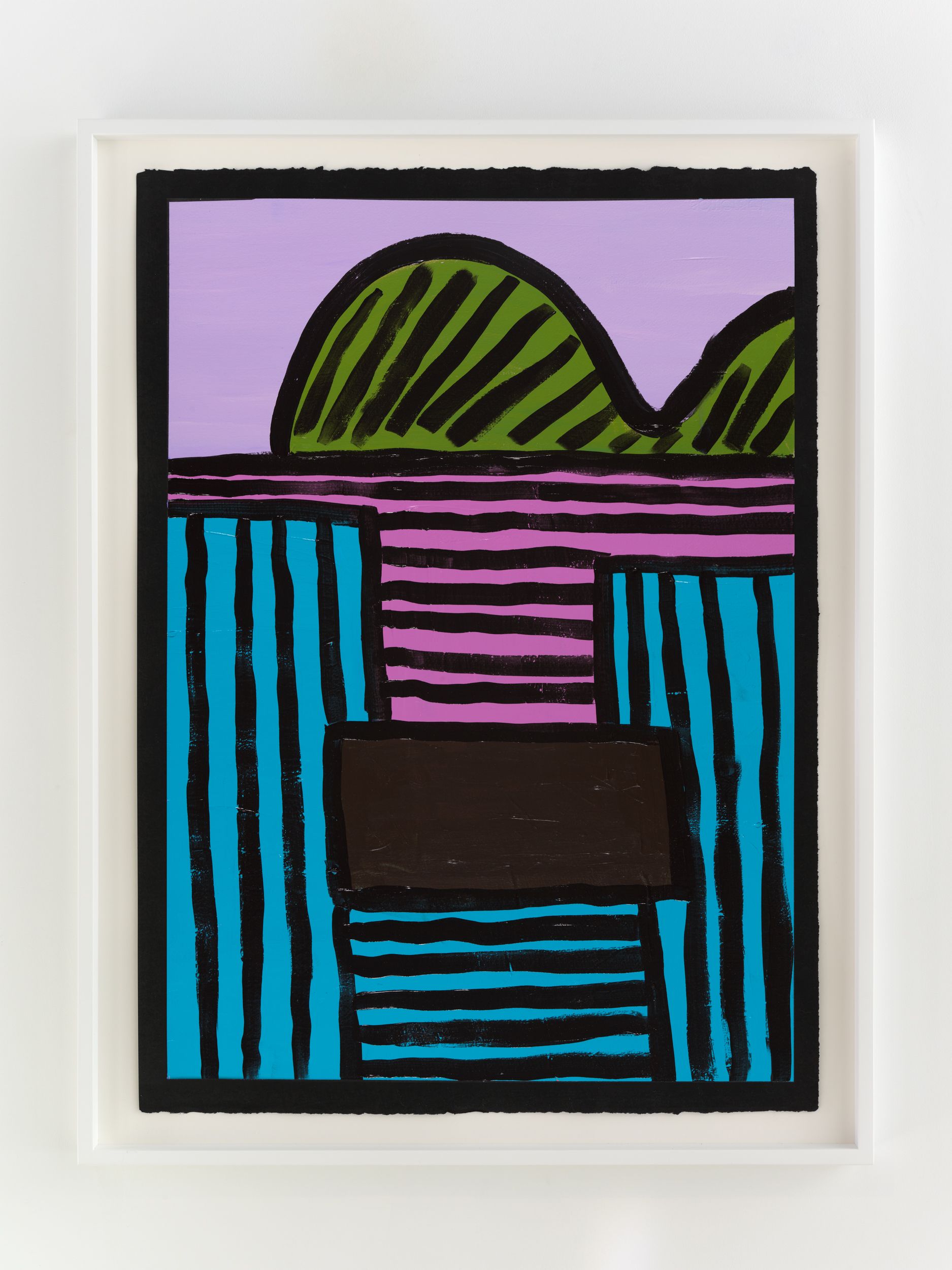

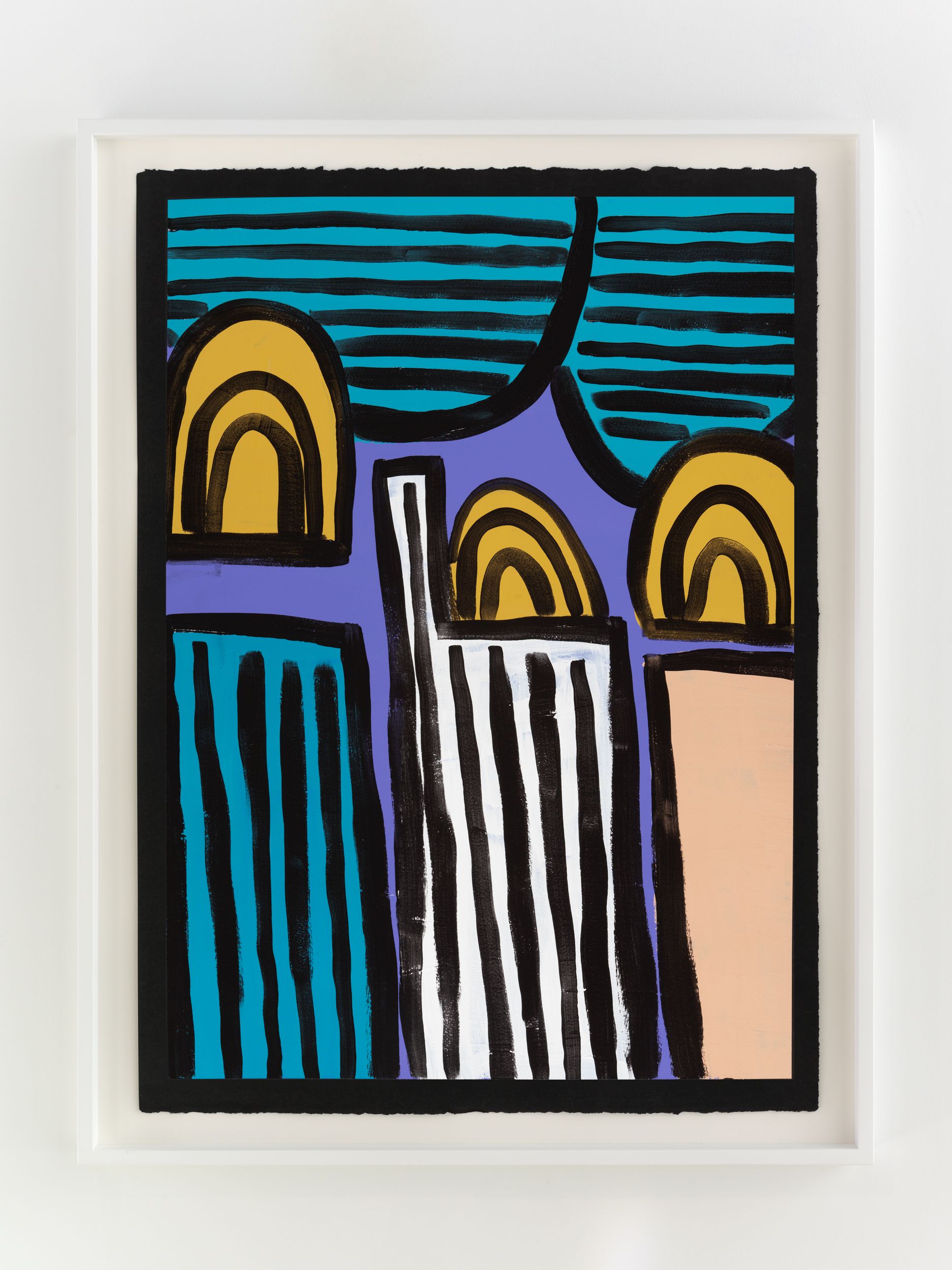

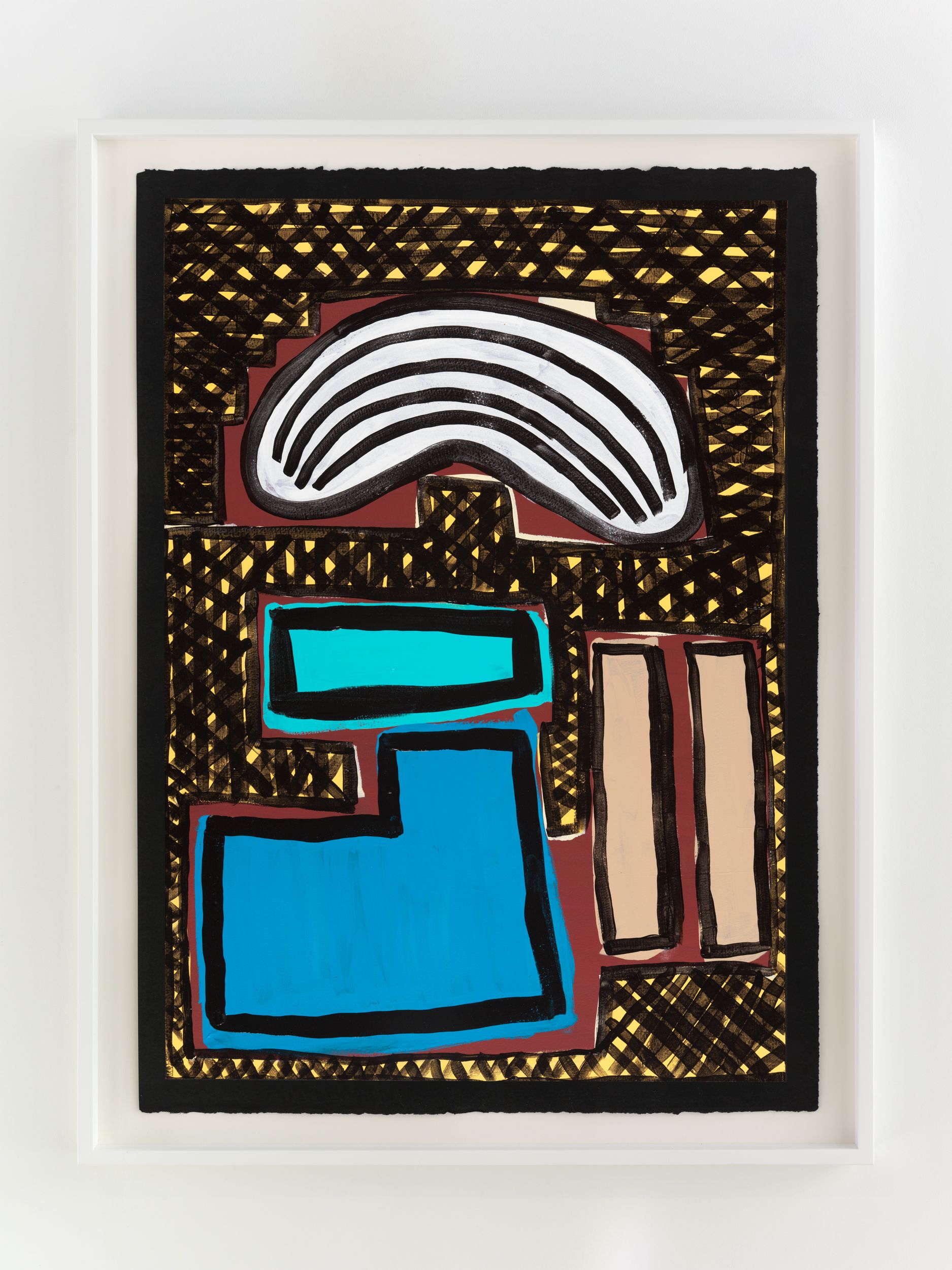

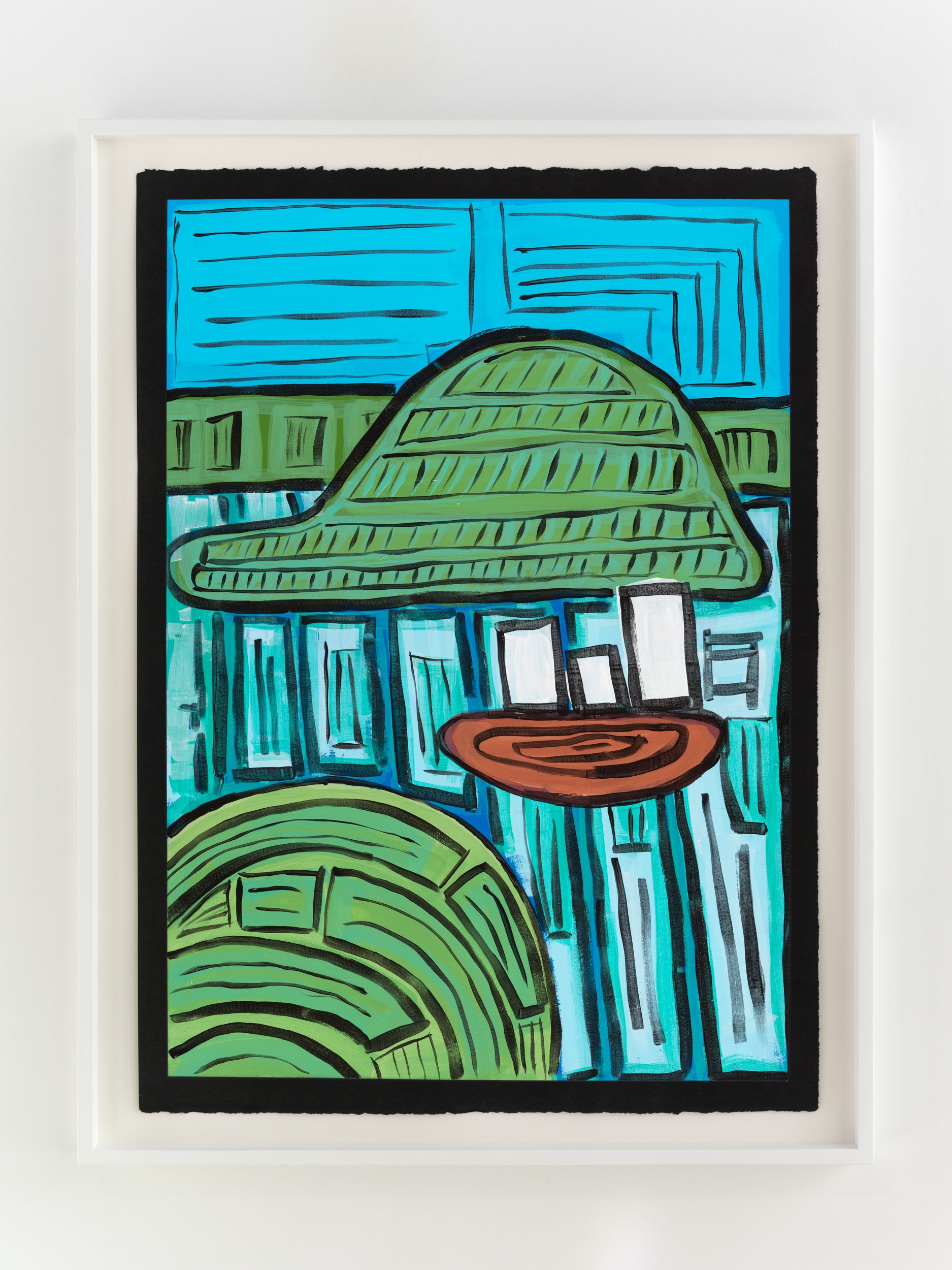

Alongside these sculptural objects are twenty joyous abstract paintings translating memories of childhood through a form of non-verbal storytelling expressed as vivid colors and thick black lines, shapes, and forms. Titles are also drawn from everyday expressions like “Carry on, son”, “Don’t give up just yet”, and “Baptize you in the name” (all works 2021). Corbett builds up layers of colors to create a visual analogue to musical notations used by various musicians. She adds, “black lines in the works serve as a graphic and expressive rendition of corporeal Blackness whilst, the use of black paper reflects what it means to be Black in different countries or the African diaspora.”

The critical theorist, Homi K. Bhabha states that hybridity is an effect of globalization but not a state that refers to two original or local cultures. He speaks to a ‘third space’ that enables other or new identities to emerge.(1) This ‘third space’ displaces the histories and cultures that constitute it and instead, new structures or identities emerge. Hybridity in this context means that they express in-betweenness or multiple identities in their form: Are they vessels or sculptures? And in function: Ceramics or performative objects? It is up to the viewer to decide.

Corbett’s wider practice is deeply rooted in the personal and theoretical. She draws from childhood memories growing up in the American southern state of Mississippi, and later, the urban sprawl of New York, to personalize vessel-like objects she has previously described as being “just like bodies and stand-ins for people”. Embodied objects are differentiated by their formal qualities, i.e., height, shape, and colors, and further personified by a myriad of glazes, lacquers, and metallic lusters, painted on by brushstrokes scored to music and improvised dance and leaving traces of movement that mark her vessels’ surfaces.

Corbett continues to carefully consider the transatlantic shifts in presenting these objects in a white cube. “It certainly feels different making work to show in the UK versus the United States especially due to the Black cultural references that are specifically African American.” She adds, “Whilst I make an effort to find a thread or continuation between bodies of work, I’m also conscious that these works are speaking for and about people, so their placement within the white cube, and things like height of pedestals are important given that these represent of black bodies and you don’t want it to be too short or too high, otherwise, there’s certain height level that starts referencing the history of the selling of slaves at auctions. “I can’t escape these objects are for sale and, I have to be very mindful of that, you know.”(2)

Ceramics has long reflected the transmission of cultural exchange between diverse individuals for different geographies because it has always engaged with the social and cultural. This chameleon-like nature of ceramics, its capacity to align itself with high art, low art, the personal, political, consumerist, and the unique, has led to its evolution within the local and the global. Corbett responds to her lived experience, rooted in her physical body, but also to a multiplicity of bodies as in Angela Davis’ call to rethink of body politics when she states how: “[T]he most exciting potential of women of color formations resides in the possibility of politicizing this identity—basing the identity on politics rather than the politics on identity.”(3) In attending to the dynamic relationship between connections to the past and present, autonomy and global consumerism, and re-evaluating identity formations, not as static or aligned but constantly in flux while negotiating transcultural forces, Corbett reminds us how operating from a position of hybridity in ceramics she argues for the importance of self-determination and the right of a community of people to determine their own political, economic, and cultural systems through a futurity where object histories are born from Black female subjectivities.

—Jareh Das

Forthcoming projects include a solo exhibition at Tate Britain in 2022 as part of its “Art Now” program.

Born in New York in 1989, Corbett is currently pursuing her practice-led doctoral degree in Fine Art at the Ruskin School of Art and Wadham College, University of Oxford, England. Corbett was awarded the Turner Bursary from the Tate in July 2021. She lives and works in Oxford, England.

Shawanda Corbett: To the Fields of Lilac is on view by appointment at 3 East 89th Street from January 12 to February 26, 2021.

For additional information on Shawanda Corbett, please contact Andrew Blackley.

For press inquiries, please contact Michelle Than.

Press

Wallpaper

The Brooklyn Rail

Ocula