The Lady and the Unicorn: New Tapestry

The Lady and the Unicorn: New Tapestry presents eight artists working in disparate parts of the world whose work simultaneously evokes and rejects the spirit, scale, and laborious nature of Old World textile fabrication, creating inventive explorations of material, color, form, and technique that challenge historical, Eurocentric definitions of tapestry.

Tapestry for a New Order by Andrew Gardner

The Lady and the Unicorn: New Tapestry presents eight artists working in disparate parts of the world whose work simultaneously evokes and rejects the spirit, scale, and laborious nature of Old World textile fabrication, creating inventive explorations of material, color, form, and technique that challenge historical, Eurocentric definitions of tapestry. Drawing its name from the six famed fifteenth-century monumental Flemish weavings at the Musée de Cluny in Paris, collectively known as La Dame à la licorne (The Lady and the Unicorn) that are together considered among the finest examples of Renaissance tapestry arts, the show presents work by artists who manipulate woolen felt, metal wire, leather belts, and pandan leaves, among other materials, to create awe-inducing objects that chart new terrain not just for tapestry, but for contemporary art as a whole. Textile has long been considered a high art globally, a process and practice as synonymous with human civilization as agriculture or animal domestication; weaving cultures from the Andes and Mesoamerica to the island nations of the South Pacific and Japan have created both functional and decorative works in fiber for millennia.

Today, taste and appreciation for fiber-based art is at an apex as a new crop of artists employ pliable media to create monumental and time-intensive artworks that recall textile’s historically global reach. Among those presented at Salon 94 are Mitsuko Asakura (Japan), whose silk and woolen plain-weave tapestries are meticulously hand-dyed in rainbow hues, not unlike the brightly colored, large-scale abstract felted forms of Sagarika Sundaram (India/USA). Some, such as Porfirio Gutiérrez (Mexico/USA) and Margaret Rarru Garrawurra (Arnhem Land/ Australia), approach dyeing fiber as an act of ancestral knowledge sharing. Still others conceive of textile as an embodied process, as is the case with Felix Beaudry (USA) and Qualeasha Wood (USA), who rely on industrial textile machines to produce personally resonant works. Meanwhile, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane (Mexico) and Adeline Halot (Belgium) expand horizons for textile, employing a range of unconventional media to create works that exist in three dimensions. International in scope and broadly focused on cloth in its most expansive notions, The Lady and the Unicorn: New Tapestry showcases a group of artists whose work speaks to the innovation and range of contemporary fiber art.

Mitsuko Asakura, Waltz, 2023

Mitsuko Asakura’s knowledge of textile practices—both classical and modern—runs deep, and it was her discovery of European Renaissance tapestries some fifty years ago that both instigated her own practice as a textile artist and formed the inspiration for the title of the exhibition. The artist was raised in a neighborhood of Kyoto that was the city’s historic epicenter of kimono production, and a kimono maker who worked with Asakura’s father, himself a noted silk painter, hired Asakura as an apprentice dyer at the age of sixteen. She quickly developed a deep understanding of the silk-dyeing process, especially fascinated with the ways that warps and wefts in varying colors could be drawn together to create chromic unity. Dyeing her fibers exclusively in Kyoto well water, today Asakura continues to draw on her deep knowledge of color, creating silk and wool tapestries that recall the scale and intricacy of Flemish and French textile artisanry merged with the painterly mastery and rigorous detailing of Japanese kimonos. Her Waltz series, begun in the 1970s, marks her first attempts at working horizontally, inspired by the landscapes she encountered on a research trip to Europe. The works resemble vast color-field paintings that have been unraveled and, in a nod to the obi belts in kimono tradition, are variously folded over in sections, bold examples of interlocking color and unbounded thread. “The structure of weaving is comparable to that of pointillism in painting,” says Asakura. “Colors never really mix together in textiles; they keep their distinct colors and fresh transparency under light.”

One artist who might beg to differ, however, is India-born, New York based Sagarika Sundaram, who uses felted fiber as a painter uses paint, laboriously layering wisps of wool, dyed variously in bright, saturated colors, into unified abstracted compositions of intermixing color. Felt is raw fiber brushed repeatedly with water and oil that, when dried, creates a uniform, solid surface. The heavy insulating power of the material inspired nomadic peoples in the Himalayas to develop felted structures such as ger (often known by the Russian name yurt), cocooned environments designed for braving harsh winter conditions that functioned much like the tapestries that lined the walls of drafty European castles. Drawing on the history of felt as a structural material, Sundaram experiments with works of gargantuan proportion, creating works like Sight Unseen (2024) that build layers of color with both precision and faith. Composing her abstractions backward before flipping them over and carefully manipulating the surface, the artist allows unpredictability to play an important role in forming the finished surface of her fiber abstractions.

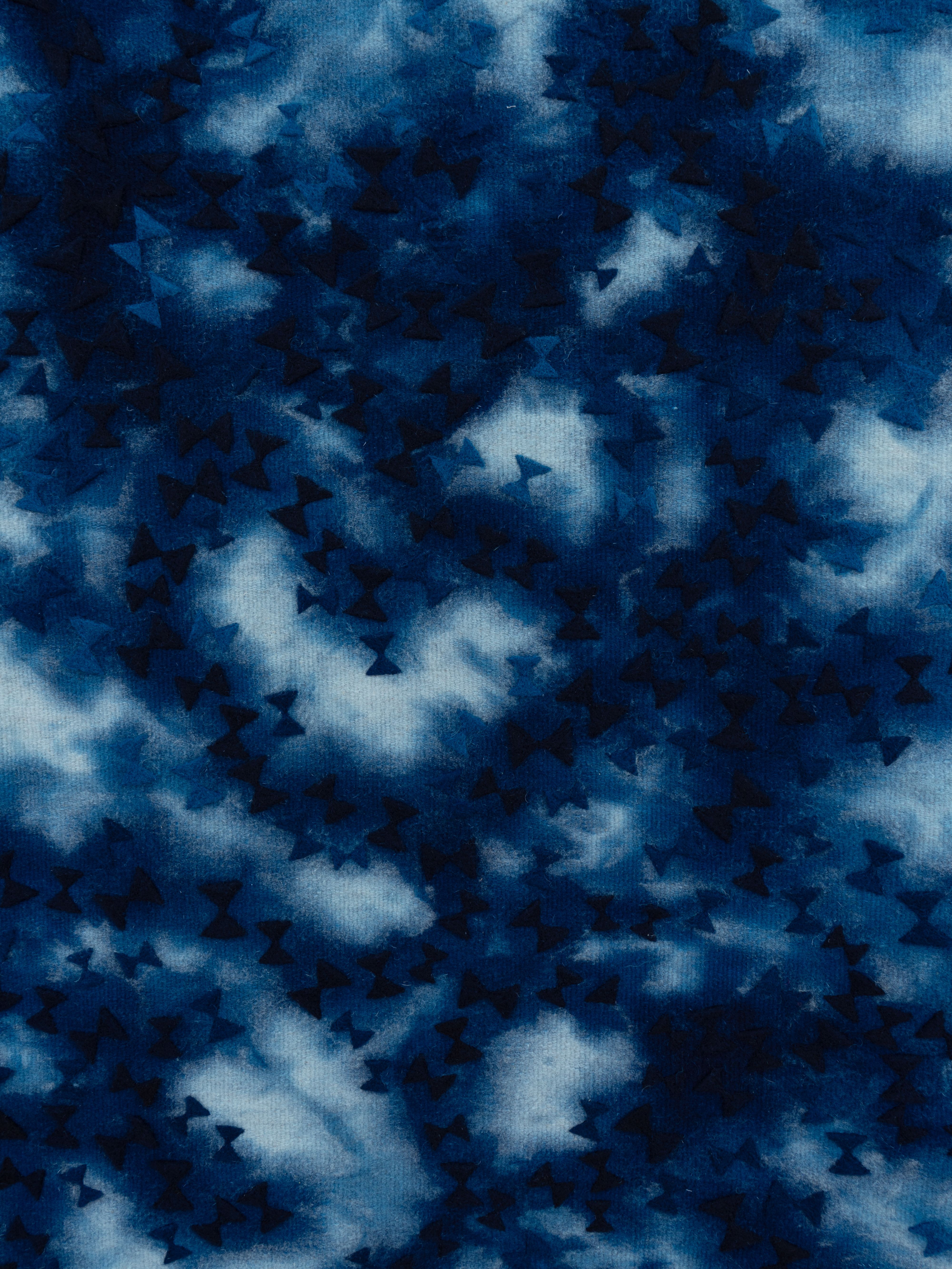

Porfirio Gutiérrez,Trails of Tears, 2024

Likewise, the relationship between color and abstraction lies at the heart of Porfirio Gutiérrez’s practice. His family’s weaving atelier has helped revive the art of natural dyeing in Teotitlén del Valle, Mexico, a small village in Oaxaca state known as an epicenter of weaving for over two millennia. The Zapotec, a people indigenous to the area, are known for exacting weavings dyed with natural materials: pericón, or Mexican tarragon, for yellow; indigo for blue; and cochineal, a parasitic insect found on prickly pear cacti, for red. But for the past several decades, these traditions lost out to globalized business interests, with Zapotec weavers incentivized to produce textiles made with synthetically dyed fibers for the tourist trade. Gutiérrez, who left his ancestral home for California at eighteen, returned some ten years later with a newfound appreciation for the artisanal precision of his ancestor’s craft. He brings a contemporary perspective to indigenous tradition in works like Paquimé (2024) and Unity (2024), that meld traditional Zapotec motifs with the spirit of Mexican modernist geometric abstraction.

Margaret Rarru Garrawurra, Dhomala (Sail), 2024

Much like Gutiérrez and Asakura, color is at the heart of Margaret Rarru Garrawurra’s work, intrinsically connected to its place of origin. A senior artist from the Milingimbi community in Australia’s coastal Arnhem Land, Rarru carries forward the textile traditions of her ancestors with purpose, positioning Aboriginal textile fabrication and traditional dyeing techniques as central to her indigenous community’s cultural preservation. Now in her eighties, the artist has been weaving and painting since childhood, when her mother and grandmother taught her to shape and dye the abundant pandan leaf into a medium for limitless tactile exploration. The traditions of pandan weaving run deep in the community; women across generations partake in the process of transforming plant matter into everything from small baskets to monumental weavings. Among this community in the tropical islands of the Northern Territory, Rarru is a respected elder, especially revered for her distinctive black dye (mol), the recipe for which is known only to those to whom she grants special permission for its use. Her large-scale works, including a massive fourmeter- tall tapestry called Dhomala (Sail) (2024), whose form is evidence of the centuries-old cultural exchange between the Yolŋu and the Macassan traders of Southern Indonesia, is banded in a spectrum of her signature black and a golden yellow, one of the many earthen tones she employs in her practice.

Felix Beaudry, meanwhile, relies on a different kind of natural palette: that of human skin. Born in Berkeley, California and now based in Kingston, New York, the artist employs a specialty industrial knitting machine imported from Germany into which he feeds his own drawings of nude bodies and body parts. The machine then mechanically interprets these drawings into knitted fiber, producing fabrics that become stuffed oversize bodies, disembodied heads, elongated arms, wearable body suits, and figurative wall tapestries. His installations of soft, enormously scaled, and fantastical corporeal forms situate fabric as central to fashioning and refashioning one’s self image, as in Bury Me in His Tits (2020), a tufted wearable sculpture that resembles an oversized sweater of a male torso, or Fire Feet (2024), a pair of gigantic pink feet that grossly distorts the proportions of the wearer. Together, these works play up tropes of male power and masculinity, allowing one to experience the power and “boyish fantasy,”as the artist says, of the kind of virile male body currently pervasive in our politics. For Beaudry, skin and clothing are inextricably linked, confusing, as the artist says, “what is internal and what is external, or how you can control how you’re seen.” In this way, clothing forms a second skin, one that allows the artist, who identifies as trans, to explore the malleability of gender expression.

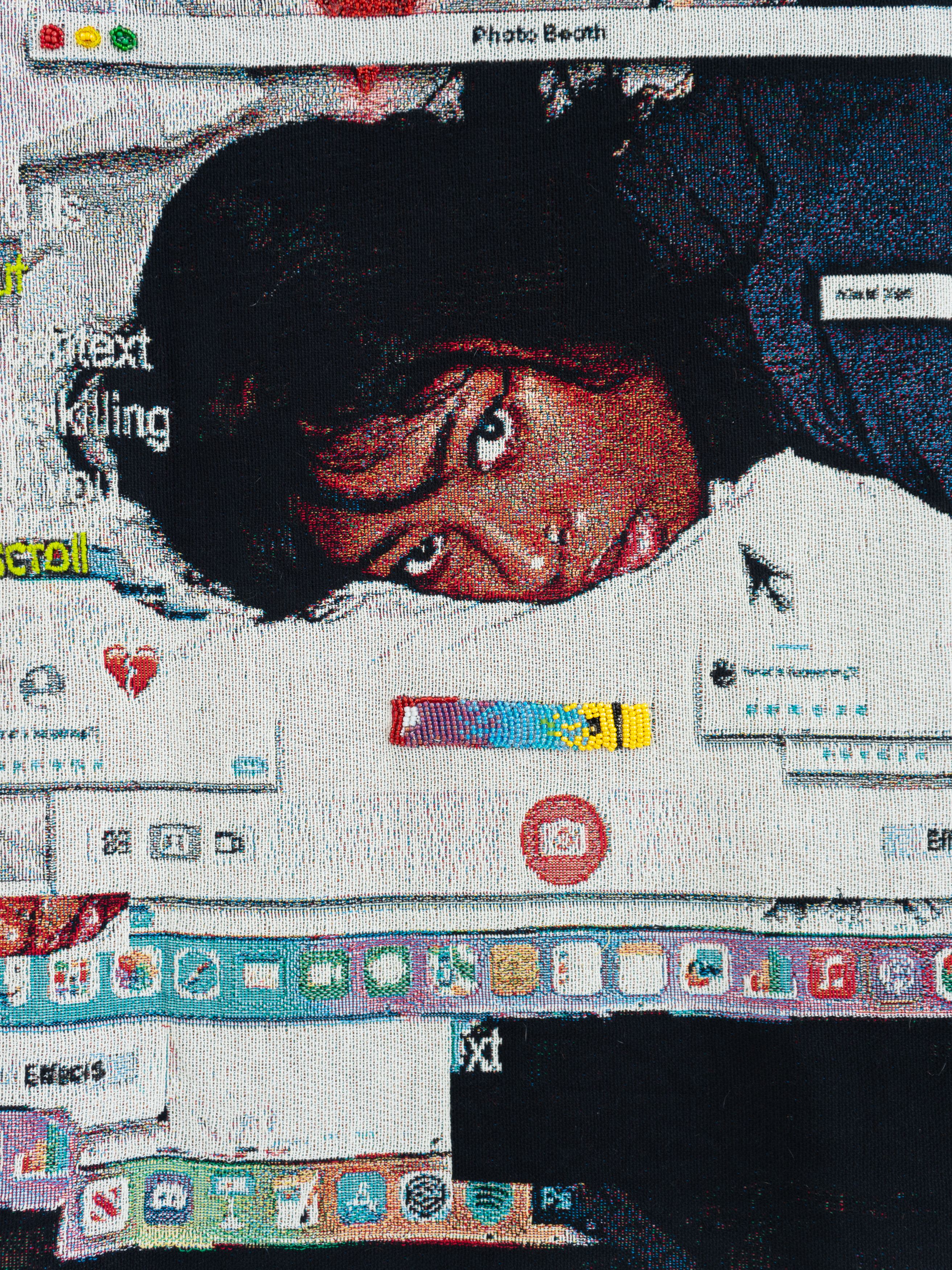

Qualeasha Wood, bed rot, 2024

Qualeasha Wood views her work as a project to construct or redefine identity through the construction of cloth. Her photocollages of digitally derived imagery, which meld self-portraits with references to internet avatars, memes, and social media, become the basis of mechanically woven jacquard weavings that she hand-embellishes with beads, merging digital pixel with tangible stitch. “Working in textile is a way of archiving the fluidity of the online,” the artist says. “This is an attempt to cement something that can still shift, because the weave continues to stretch over time and the beads move.” Based in Philadelphia, Wood is the central protagonist of her own work, drawing on Catholic imagery and other religious iconography to boldly position the Black queer femme body as a site for veneration and respect rather than objectification and denigration. Works such as K.M.B.A. (2023) position the artist’s backside, curves and all, at the forefront of the image, making visible the elements of the body that are often hidden from plain sight, thereby directly challenging art-historical conventions of the “idealized” female form. By placing her own visage at the center of the story, often situating herself in altar like environments, the artist proposes tapestry as a magisterial art form where one’s image can be reclaimed from an internet culture steeped in incivility.

Bárbara Sánchez-Kane, Look 3, 2023

A similar rejection of patriarchal notions of beauty and self-presentation inform the work of Mexico City-based Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. The artist and fashion designer, who interchangeably uses he and she pronouns, rejects Mexican notions of machismo through his wearable sculptures and sculptural wearables, not unlike Beaudry’s practice. Rendered in unconventional materials, her work questions our associations between garments and bodies, and how those garments can be sites for both restriction and liberation, as in Look 3 (2023), a sculptural construction of woven red leather belts that defamiliarizes the human form, cocooning and obscuring the wearer with its armorlike form. Pieces such as lambskin biker jackets that reveal the wearer’s nipples or reconstructed backless army uniforms that expose red lingerie are central to his efforts to subvert the binary, proposing instead that clothes, which play a crucial role in the performance of one’s identity, can themselves be artistic provocations, too. “We don’t live in a naked society,” the artist says. “How, for example, did the Mexican government use uniforms to create a sense of national identity after the revolution? Can you make people want to be part of a group without uniforms?” In this way, Sánchez-Kane speaks to the ways that pliable media of all kinds can become a conduit for both protection and transformation.

Adeline Halot, REEF ST R.03, 2023

Transformation of a different sort is central to Adeline Halot’s finely rendered weavings, which evoke a state of suspended animation, moving objects frozen in time. Hovering miraculously overhead, her ethereal works of unreality visualize the metamorphic possibility of textile. The artist and designer, based in Brussels, employs surprising media to great effect. Combining flax linen—her native Belgium is the historic epicenter of the fabric’s production—and stainless-steel wire, she concocts shimmering tapestries that merge traditional fiber production with modern precision. The softness of linen and hard malleability of metal create ample opportunities to mold the textiles into tapestries that appear on the edge of motion, just on the cusp of a new existence. This lively dance in the liminal space between real and fictive is heightened by the metal wire that reflects light and the linen threads that filter it, creating a play of light and shadow that envelops the room in soft, filtered lighting. Grand in scale, Halot’s work is illustrative of both the deeply-ingrained traditions of tapestry and the technological advancements that are charting new frontiers for weaving in the twenty-first century.

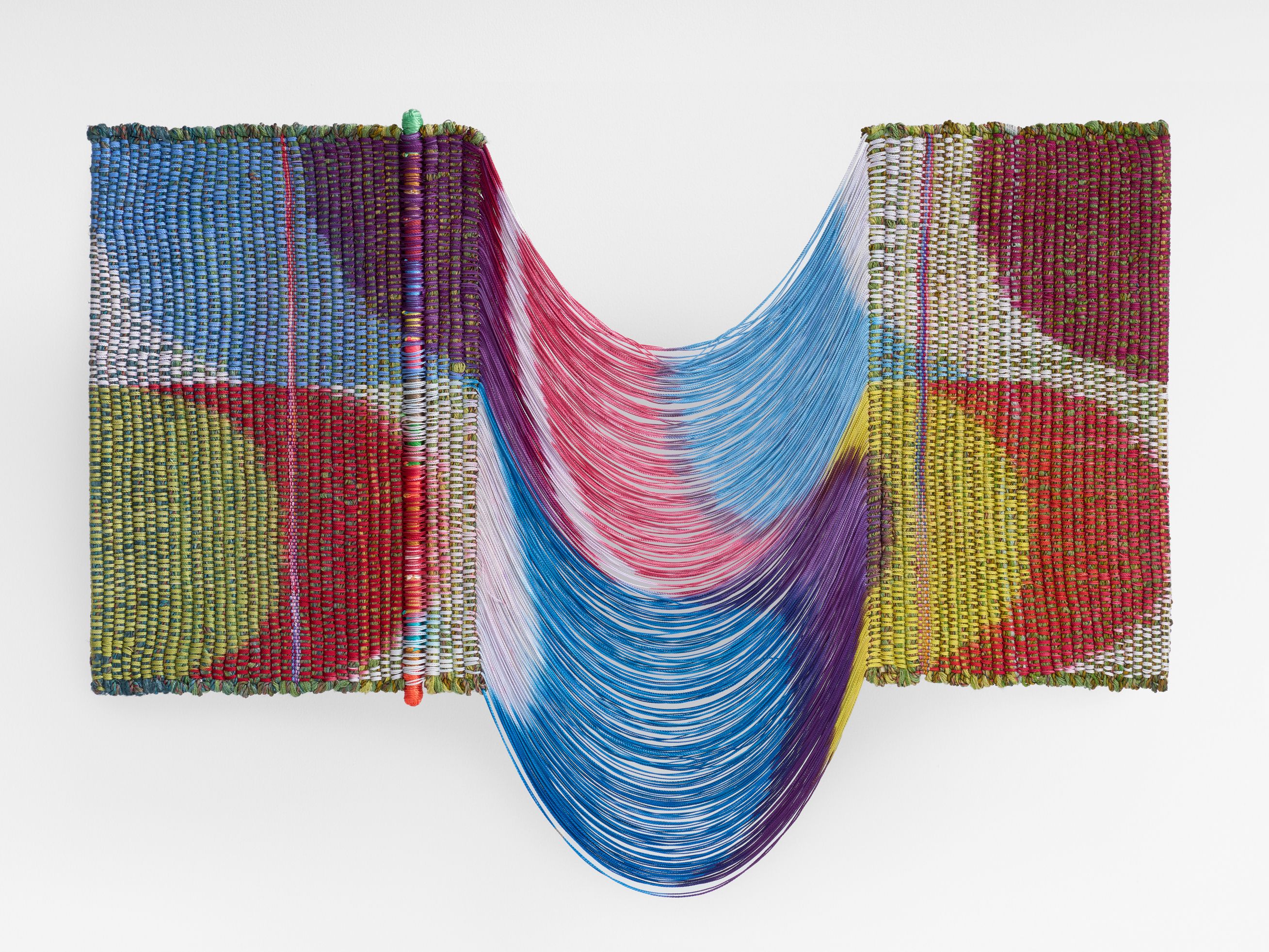

Hella Jongerius, Textile Study 4, 2024

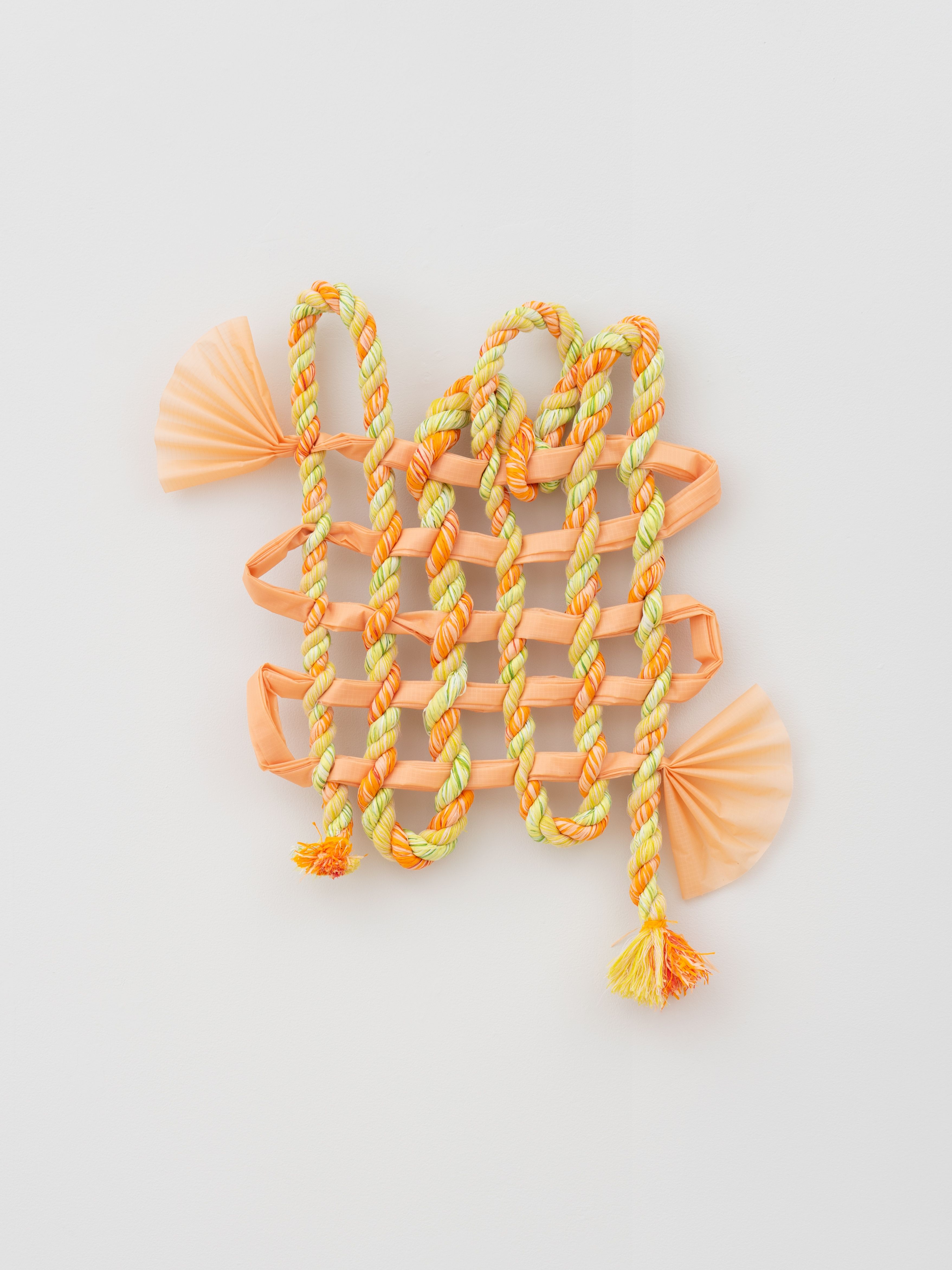

Among those at this century’s cutting edge is the celebrated Dutch designer Hella Jongerius, whose solo exhibition Roped Beings is also on view with Salon 94 Design. Marking her first presentation in New York since 2013, the show in particular highlights Jongerius’s facility with fiber, offering a compelling dialogue with the eight artists in The Lady and the Unicorn: New Tapestry. A wall of her prodigious assortment of Textile Studies joins the display of tapestry works on the ground floor, works that employ a remarkable weaving process she describes as “third thread,” in which warp and weft are alternated in varying directions to create fully contained miniature woven forms. These works are an extension of the Berlin Jongerius Lab team’s longstanding investigations of everyday materials—rope, tissue paper, silk, and hand-dyed wool, to name a few—used to create inventive propositions for textiles by knotting, weaving, or braiding. Presented alongside furniture works and her clay vessels, this display of the Textile Studies speak to Jongerius’s adeptness in navigating the fluidity of function, form, and materiality—and the gallery’s commitment to breaking down the walls that confine design from art.

With this show, a new chapter in the history of global fiber art is being written, harkening back to the days long before oil painting or photography were the dominant modes of visual expression in the West and tapestry reigned supreme. The six Cluny tapestries are among the most well-known examples of this tradition, notable as much for their fine production value as for their unusual representation of women at the center of naturalistic scenes that are commonly agreed to be allegories of the five senses. At a moment where the fundamental freedoms of women to make choices about their own bodies is under assault, where rampant inequality and climate devastation are a central fact of life, and where patriarchal and autocratic tendencies continue to pose challenge to democratic norms, might we find a way move forward in the spirit of the sixth panel—inscribed À mon seul désir (To my only desire), which scholars have argued represents a more ephemeral human sense, intuition? The Lady and the Unicorn tapestries offer a view of humanity and nature in balance, a view of a world that could be if we are willing to work together to make it so. In this way, the group of highly inventive artists presented at Salon 94 offer evidence that tapestry is an inherently political medium, a historically resonant practice that even today transcends borders, material constraints, and gendered expectations, to subvert the status quo and offer a compelling vision of a more just and equal future.

Press

Hyperallergic

artnet news

W Magazine

The Guardian