Judy ChicagoThe End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction

The artist reflects on her own mortality and appeals for compassion on behalf of endangered animals and ecosystems.

Installation Views

The National Museum of Women in the Arts presents Judy Chicago—The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction, on view September 19, 2019—January 20, 2020. Visually striking and emotionally charged, the newest body of work by feminist icon Judy Chicago continues her commitment to challenging the status quo and advocating for social change. Through a series compromising 30 paintings on black glass, seven painted porcelain works and two large-scale bronze reliefs, the artist reflects on her own mortality and appeals for compassion on behalf of endangered animals and ecosystems. Viscerally bold, the graphic style of these works communicates the intensity of Chicago's personal contemplation of her own death as well as the death of entire species'.

While Chicago is best known for The Dinner Party (1974)m the renowned iconic mixed-media installation that celebrates the legacies of women throughout history, this new exhibition also connects with her many other prescient bodies of work—on sex, birth, death, violence and the natural world. Chicago has built her career on pushing boundaries, and The End is no less audacious than her earlier projects.

"In many ways, this series is the culmination of 50 years of studio practice, a practice that has taken me on a journey of discovery through many different topics expressed through a wide range of techniques," said Chicago. "In a world in which women's cultural production continues to be undervalued, discounted or marginalized, I am pleased to premier this work for the first time at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the only museum in the world dedicated to ensuring that women's art is preserved."

"Judy Chicago is a formative figure in contemporary art. She has spent her career exploring social issues, expressing a unique vision that incorporates personal experience with a concern for the wider world," said the NMWA Director Susan Fisher Sterling. "Brave, earnest and vulnerable, Chicago often has provided voice for those she feels have none. We are excited to present this new body of work that explores the next frontier for her, for us and for others on this planet—mortality."

AGING AND DEATH AS THE FINAL TABOO

Our society has an undeniable discomfort surrounding aging and death. In The End, Chicago tackles mortality, both as a universal human experience and as a personal rumination. In a culture that prizes youth and beauty—particularly for women—Chicago's stark images are a potent antidote. She also presents the mortality of entire ecosystems that have been irreparably damaged by the action, or inaction, of humans. With this series, Chicago continues her history of merging the personal and political with grabbing colors, technical mastery and uncomfortable subjects.

In the first part of the series, "Stages of Dying," executed in china paint on white porcelain, Chicago depicts a nude older woman progressing through the five stages of grief. As defined by pioneering psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, these stages can relate to grieving the death of a loved one as well as the contemplation of one's own inevitable end. The figure, whose baldness renders it somewhat androgynous, expresses an archetypal "everywoman," a universal figure to whom death idealized, youthful, supple and objectified by centuries of mostly male artists—Chicago presents an aged body. Her wiry and wrinkled protagonist refutes the trappings of stereotypical femininity.

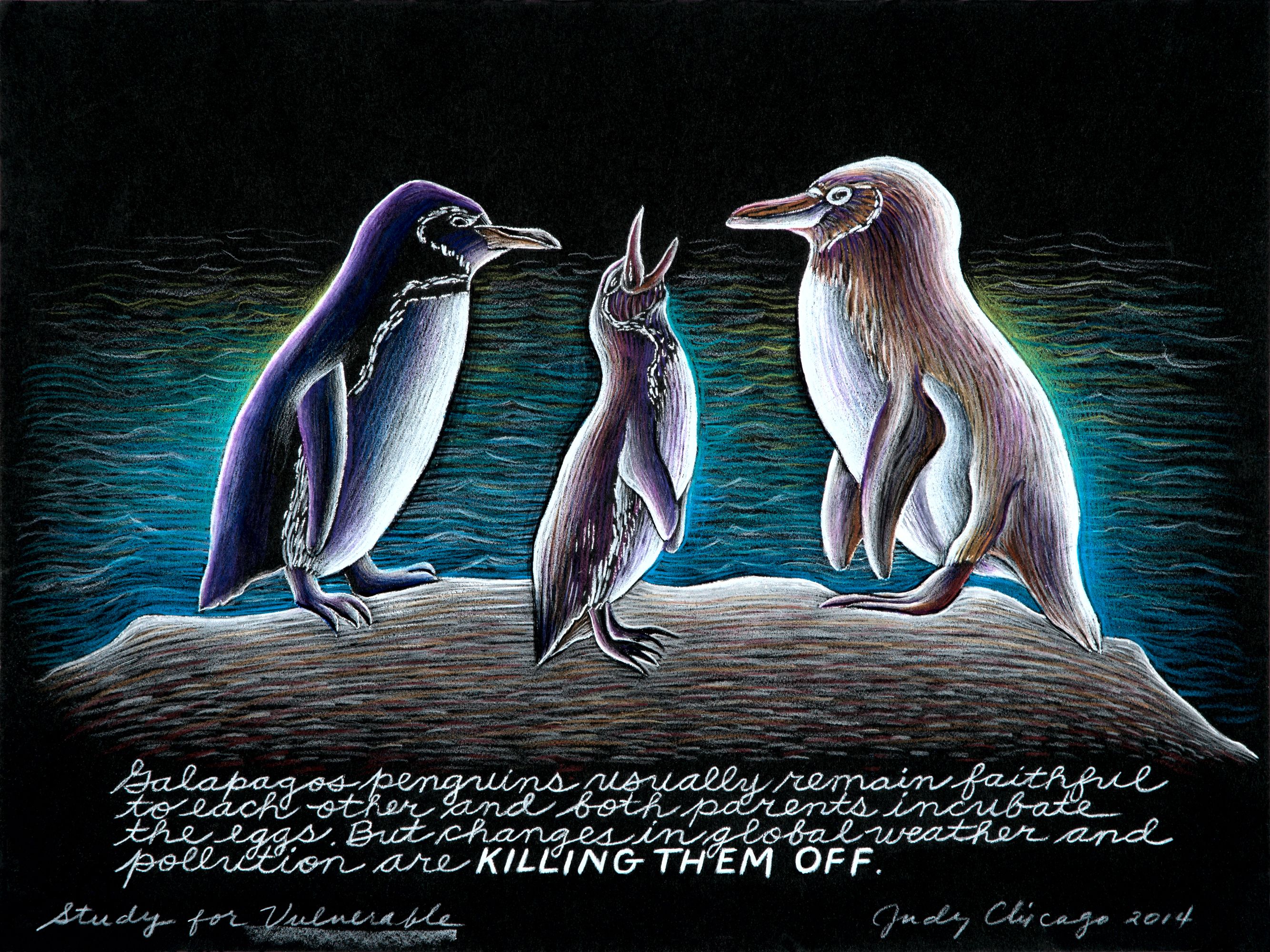

The second and third parts of the series, "Mortality" and "Extinction," are made from kiln-fired glass paint on black glass. Chicago expresses anxiety about how she might die in the "Mortality" contemplation, yet they are also intensely personal for a woman entering her ninth decade. A more collective sense of anxiety and sadness is expressed in the "Extinction" panels, which depict, in often graphic detail, groups of animals and plants that have been irrevocably harmed by humans, from elephants killed for their tusks to trees flayed for their bark. Chicago's handwritten script—a part of her practice since the early 1970s—appears in each part of the series.

While porcelain and glass panels form the majority of this series. The End also includes two large-scale bronze reliefs. The first is a half-length image of Chicago—her head against a pillow, eyes closed and hands emerging from a shroud with a bouquet of lilies. This self-portrait is modeled directly from the artist's face and recalls the long tradition of death masks. The second, larger bronze is an assemblage of creatures threatened with extinction. The work evokes the visual language of mounted hunting trophies, calling into question the ethics of killing purely for sport. Chicago has previously worked in bronze, however, the works in The End are among her largest to date in the medium.

Artistic Practice

Painted porcelain has been part of Chicago's artistic practice since the 1970s when she and a team of volunteers created The Dinner Party. Their use of embroidery and porcelain paid homage to practices that have historically been considered "women's work." Throughout her long career, Chicago has used materials frequently associated with women—including porcelain, embroidery and glass—to challenge the gendered binary of high art versus decorative art.

Glass painting is a time-consuming and laborious process—multiple firings are needed to achieve an artist's desired effect. These works demonstrate the skill that Chicago has honed over the years, beginning with The Holocaust Project (1985-1993), a series of works bookended by stained-glass installations. In 2003, through an artist's residency at the famed Pilchuck Glass School outside of Seattle, she continued to expand her proficiency in the medium.

Judy Chicago—The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction is organized by the National Museum of Women in the Arts. The exhibition is made possible by the MaryRoss Taylor Exhibition Fund. Additional support is provided by the Sue J. Henry and Carter G Phillips Exhibition Fund and the museum's members.