Myrtle Williams Spirit of the Sisterhood

“To me, women rule the world”

- Myrtle Williams

Installation Views

Artwork

Spirit of The Sisterhood By Romi Crawford

Edmonia Lewis’ Hiawatha, 1868, Meta Vaux Fuller’s Ethiopia Awakening, 1921, and Augusta Savage’s Gwendolyn Knight, 1934-5, serve as proofs that African descended women artists have been drawn to the bust form, (loosely defined as a mode of portraiture meant to portray a personage from the shoulders up), for more than a century. Compellingly, these women artists often used it to convey and inventory an alternative list of heroic or notable figures, including those from more minoritized cultures and social contexts, indigenous and black persons, women, etc.

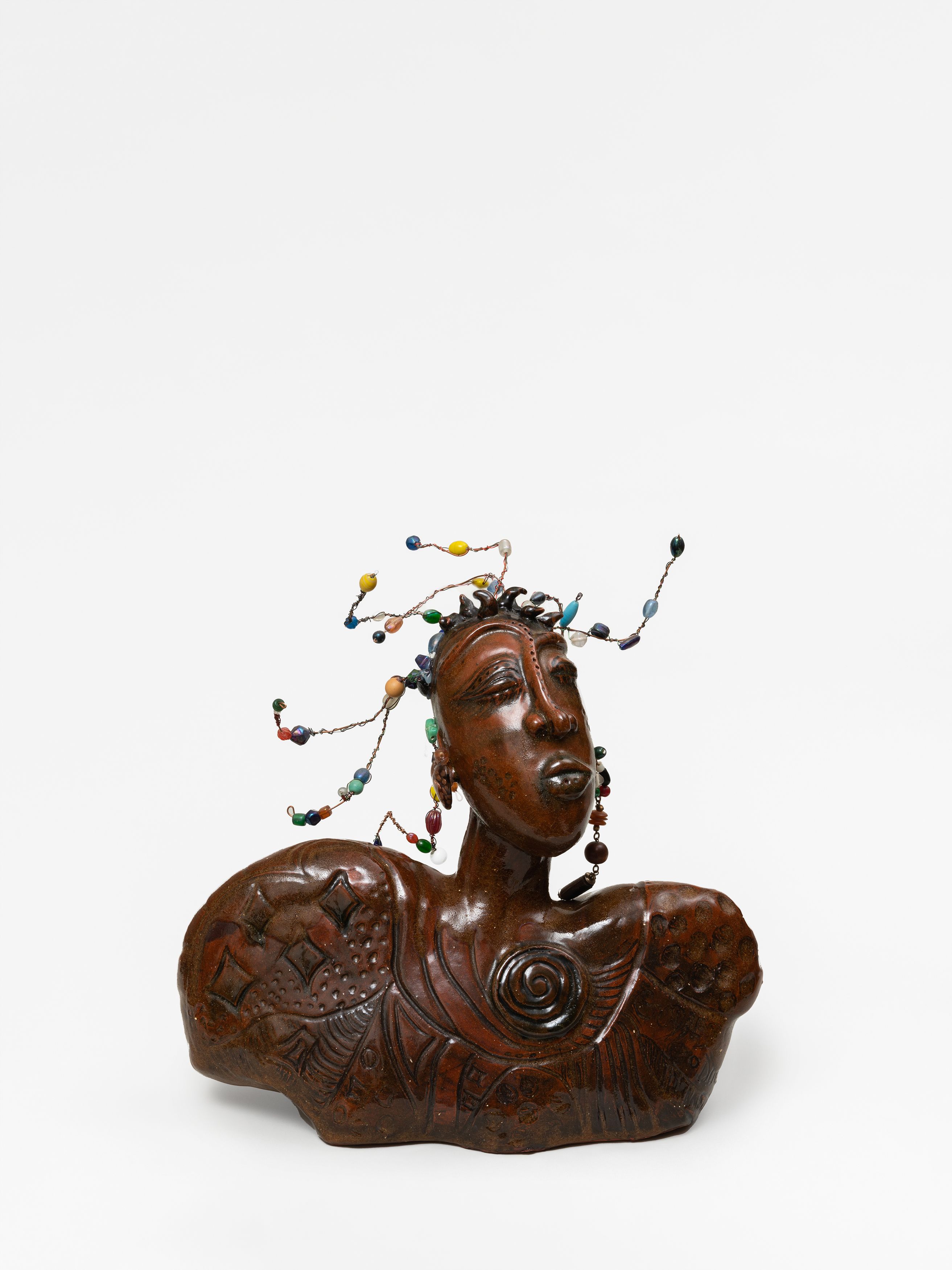

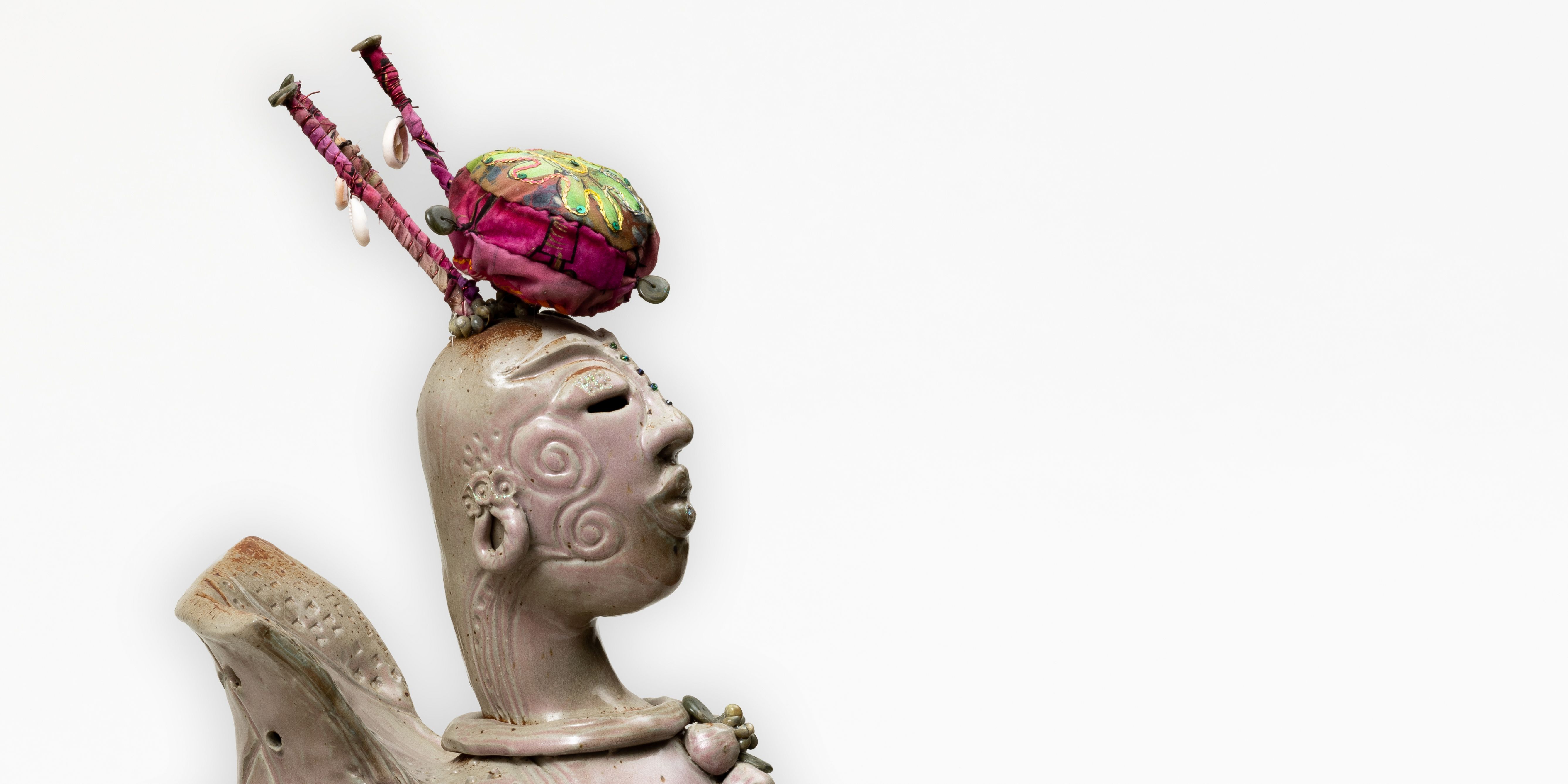

Myrtle Williams’s works in Spirit of the Sisterhood, her first solo exhibition in New York at Salon 94, find lineage with the works of this august group of women artists. While she doesn’t work in marble as Lewis did, nor plaster or bronze, like Fuller and Savage, her whimsical ceramics similarly revise, riff upon, and make exciting modifications to the classical bust form.

Williams who has been making work for the past 35 years, honed her craft close to home, in the ceramic studio of Montgomery County Community College in Pennsylvania. This span of time in the studio here translates into a clear set of formal convictions, --even as the work morphs, and has range and breath, from series to series. Thematic certainties are also apparent in Williams’s work to this point, such as her fervent, adamant interest in positioning and platforming black women. Her Singers series, which includes representations of black women musical figures, Ella Fitzgerald and Lena Horne for example, and the Activists series which includes figures such as Septima Clark and Modjeska Monteith, both attest to this.

The womanist agenda may be a bit less obvious in the figures that make up the Spirit of Sisterhood exhibit, which with extra heads and both rounded and more tentacle-like protrusions, have more complex, fanciful, and unrealistic bodily arrangements than those in Williams’s other projects. Still, ever insistent upon the power and strength that she ascribes to women and black women in particular, Williams confidently posits that these are female spirit objects, deities or goddess-like. In effect, they are meant to express her view that “women rule the world.”The works in Williams’s Spirit of Sisterhood exhibit are expressions of this argument, the optimism of which for some might be seen as rousing or questionably provocative (given economic and social metrics). What is certain is Williams’s rendering of objects that are sovereign in their way—symbolized by the disregard for the most basic figurative norms. They are variously double-headed, some seemingly headless, others swayed and bent, all shape shifting away from any reductive, flat understanding of what a woman is.

And in other ways too, her objects are free and unfettered. They are also rather unique as ceramics and unburdened by the expectations for that form and medium. The ceramics in Spirit of Sisterhood, which are for the most part non-vessels, do retain some connection to the tradition of utility that ceramic work often (rather mistakenly) carries with it. The few works in the exhibit that read more directly as containers, such as the Mask Vessels (2004) and the Footed Trays (2017), might help to orient the viewer to an understanding and interpretation of the deities or goddesses as equally effective for storing. What they store, or rather hold and maintain, are references to African culture, including practices of scarification as well as myriad materials such as a cowrie shells, African textiles, beads, and porcupine quills; many of which Williams acquired or encountered on her many travels to the African continent and other parts of the world.

The other worldliness of the Williams’s figures is in part balanced by these textile and fabric interventions. They serve as potent markers of, or references to, the real. A work titled Lupita for example has fabric incorporated into the back of the figure. With the darkened glaze and one’s awareness that Williams is concerned first and foremost with representations of black women, it is hard not to see this as a reference to the whip-lashed slave body, most directly the tree shaped scar on the back of Sethe, a character from writer Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved, who states that “I got a tree on my back and a haint in my house, and nothing in between but the daughter I am holding in my arms.” Williams’s work offers a re-imagining of this scar, healed in the form of a beautiful textile. While there are scarifications on the surfaces of many of the ceramics, they read as part of a more Africanist aesthetic. In this work, on the other hand, swapping the scarred surface with an ornate fabric, onto the prime location for lashings (the back) is poignant. In effect, the textile moments, which are draped, balanced, or intertwined into Williams’s ceramic forms negotiate and balance the fantastical and the more frank or real elements in Williams’s Spirit of the Sisterhood.

It matters tremendously that Williams’s work has moved beyond her studio and into public view. A disconcerting reality that hovers not so much in the work, but at a more meta level, is that like many black artists, minoritized artists, and women artists of her generation, reception for, and close interpretation of, the work has been slow. Yet, in the end, Williams has forged an arts practice on her own terms. Declaratively she has been part of other penetrating scenes and social formations; including a supportive family and her church. These circles of influence, which are very often elided in artist’s articulations of their practice, but not in Williams’s, have lent their own imprint on her work and aesthetic sensibility. She voices that she and her husband have been collecting arts work by African American artists such as Barkley Hendricks, Elizabeth Catlett, Jacob Lawrence, and Charles White and that they have amassed African masks and race inflected memorabilia once popular in the United States, because these inform the material and thematic basis of the objects in Spirit of the Sisterhood. The works ultimately draw in and absorb this range of experiences and histories, which are then interpolated through Williams’s (black) womanist objects. It is clear from the polyvalent nature of these forms that this is in no way a reductive worldview but one that is as versatile and expansive as any.

-Romi Crawford

Over the course of 35 years, Myrtle Williams (b. 1938) made over 300 ceramic female figures at the ceramics studio of Montgomery County Community College. Each layered with the textures, signs, and symbols of her travels and imbued with her lifelong desire to give visibility to Black women, her deeply personal and powerful troupe of figures glazed in black, green, and brown stoneware are her heroines of African American culture and liberation—past, present, and future. Williams and her husband, Dr. John T. Williams Sr have long championed the work of Black artists and examples of Black figuration as they amassed an extensive collection of works by African American artists such as Barkley Hendricks, Elizabeth Catlett, Jacob Lawrence, and Charles White alongside African masks, figures and rare Black dolls gathered in travels across all 50 of the United States, nearly every continent, and several countries in Africa. Exhibited for the first time in New York with Independent 20th Century, William’s elegant ceramic portraits are an embodiment of Williams’ belief that “Women rule the world”--and as such, should occupy it as powerful independent subjects, proclaiming their visibility and importance.

For additional information on the work of Myrtle Williams, please contact Zoe Fisher

(zoe@salon94design.com)

For press inquiries, please contact at Michelle Than (michelle@companyagenda.com)

Press

The Brooklyn Rail