Timothy WashingtonPucker Up

An exhibition of Timothy Washington’s wondrous, ethereal sculptural figures and totems.

Installation Views

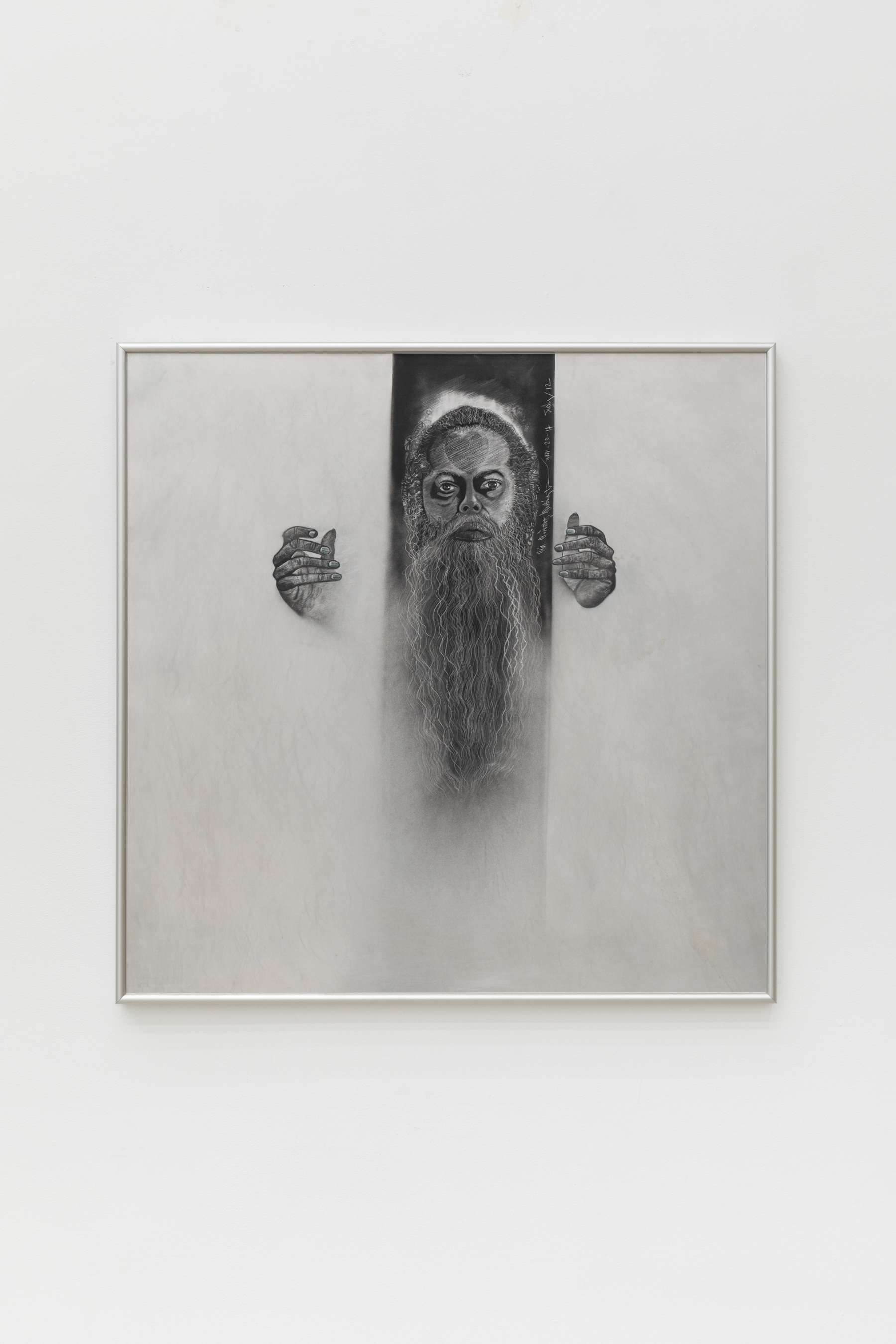

Artwork

Salon 94 Bowery announces Pucker Up, an exhibition of Timothy Washington’s wondrous, ethereal sculptural figures and totems. This will be the Los Angeles-based assemblage artist‘s first solo show on the East Coast to date, and will span sixty years of his practice. Alongside rare, early work from the 60’s and 70’s, there will be a constellation of his legendary polychromatic figures bedecked and bejeweled with ephemera culled from life. Figurative memory-wares, each personage is an active teller—and producer—of a specific story and subjective experience.

Pucker Up comes at the heels of Citizen/Ship, Washington’s solo exhibition at the California African American Museum, Los Angeles which featured a psychedelic, sound-filled installation drawing on Afrofuturistic narratives of fantasy and science fiction. In 2014, Washington was praised in Artforum for Love Thy Neighbor, his solo exhibition at the Craft and Folk Art Museum, Los Angeles which featured an “inextricability of art and craft, using street detritus, Christian imagery, and warped, alien-like human forms to question the relationships between humanity, spirituality, and the cosmos.”

Washington’s sculptures are unabashedly handcrafted and together are a celebration of play, both literally and figuratively. Washington’s forms are made by sculpting glue-saturated cotton around wire armatures that, once dry, create a hardened, textured encasement. After painting—often in his favored purple or turquoise green—these works are decidedly spangled with found objects collected from his neighborhood over many years, oftentimes culled from family and friends. Intimate effects, including pieces of jewelry, dishware, and toys are strategically placed and meaningfully grouped to engender particular readings and sightlines. Several Faces, One Race (Male Figure), 2009, includes a small mirror at average head height, which brings the viewer’s face into the composition of the work. Pucker Up, 2008, includes smiling toy faces embedded in the sculptures at knee height—generously giving alternate focal points for children. Influenced by the Kapok Tree, 2009, is a massive sculpture assembled from various media including kitchen timers—the sculpture is set to go off at various surprise moments throughout the exhibition!

Growing up in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, Timothy Washington’s childhood placed him in close proximity to the Watts Towers, which, as a child, he and his brothers would boldly climb. Washington’s investigation of the seventeen monumental, interconnected mosaic towers was at once architectural, visual, and formal and serves as a lasting and important touchstone. Washington was nineteen years old when the Watts Riots shook his neighborhood; the rebellion that was felt across the nation has influenced his life and work to date. For his entire career since the riots, Washington has sought to combine disparate elements into coherent wholes.

Timothy Washington studied at the Chouinard Art Institute with Charles White, alongside fellow artist David Hammons. Washington’s work has long been associated with others in the Black Arts Movement—the aesthetic and social sibling to the Black Power Movement—as well as those catalyzed by the Watts rebellion of 1965 including Noah Purifoy, Betye Saar, John Outterbridge, and John Riddle. Many of these artists, like Washington, came to create artworks repurposing debris from burnt and destroyed buildings, recovering the rubble from their homes and environments at large.

In the decades since his youth, Washington has become more sensitive to the relationships between materials, as well as what he refers to as the “liveliness” of objects: “When I had an etching class, the plate seemed much more fascinating to me than the print itself. And I wondered about boundaries in art. Why should the plate be considered something to use to make a paper print when I loved the plate so much more? The plate said so much more to me because it had me with it.” Washington is as known for his graphic and pictorial works— which include mixed-media collages, metal etchings and drypoints, paintings, and drawings on paper—as he is the volumetric sculptures: his object-based processes accrued from the material process of sculpture inform the creation of his visual works. Across media—and across decades—Washington’s works produce new meanings and messages indiscriminately, unearthly-inspirited, and with intentions bold and elusive alike.

Notes on Timothy Washington's Spacial Meditations

by Serubiri Moses

Timothy Washington’s art consists of both a spatial practice and the assembling of objects described by artist John Outterbridge as “editing material.”[1] The artworks, which often rise upward, according to the artist are both three-dimensional drawings[2] and sculptures. Washington’s art speaks to some questions evident in critical studies of forms of African American art: such as black literature and black music.

The question of ambivalence, which is discussed by literary theorist Hortense Spillers[3] regards the literature of the black sermon. She describes “the African-American’s relationship to Christianity and the state is marked completely by ambivalence; we could even say that at moments such a relationship gropes towards a radically alternative program.” In a similar sense, Washington’s art reveals a particular ambivalence, not specifically towards formalism, since the artist relies on disciplinary terms such as sculpture and drawing to describe his own practice,[4] but rather his art is ambivalent towards canonical art traditions typified in American modern art. Thus, his art adopts an “oppositional stance” towards both standard art pedagogy and the history of American art. In this way, we may uncomfortably situate the artist within this body of knowledge and its modern context.

In an interview, Washington speaks of his “intrinsic”[5] approach. He refers to his own idea that “everything is alive”[6], and “the degree of liveness that everything has.”[7] The intrinsic shows belonging to an essential nature. Ultimately his approach, by following this alternative essence, diverts from the academic approaches in which the artist was trained at the art academy.

Washington’s aesthetic brings to mind a second prominent topic in critical studies of black music. I refer to “social praxis”[8] as well as “social-aesthetic urgency.”[9] For saxophonist Salim Washington, “music enhances the purpose of the social event and helps the people attain greater involvement in it.”[10] For the artist, that social event is the social experience that defines black life in Watts, Los Angeles, and beyond. Salim Washington opposes the valorization of the “assertive, ingenious individual” in the art world.[11] This elaborate focus on the “individual” genius is yet another aspect that isolates Washington from dominant themes of American modern art.

The artist’s “oppositional stance” is confirmed in his collaborative and collective processes. His source materials often come from networks, friends, and colleagues, often in proximity to his own home. This sense of the “familial” in conjunction to art-making upsets the standard heroism within American art. Spillers articulates what may appear as contradictions and/or refusals in Washington’s artistic practice. She writes, “In another sense, we could say that black culture, having imagined itself as an alternative statement, as a counterstatement to American culture/civilization, or Western culture/civilization, more generally speaking, identifies the cultural vocation as the space of “contradiction, indictment, and the refusal.”[12]

A third aspect that shapes Washington’s artistic practice is its spatial considerations. Here I refer to the spatiality and locality of his practice as distinctly situated in the neighborhood of Watts, Los Angeles. This is the place of his childhood upbringing. In a panel, the artist described the locality of his practice as such: “I started from an early age walking around the block, and that was the extent of my travels.”[13] This statement not only speaks to the importance and centrality of Watts, in his formation as an artist, but similarly in the very idea of the “block” as a lexicography from which he continues to excavate. The emphasis on the block and Watts neighborhood as locales suggest a deeper inquiry in Washington’s artistic practice about place and space. Watts was by the mid-20th century a black and brown neighborhood, where in 1965 the renowned Watts riots occurred. As an extension of his attention to urban black life, the artist’s focus on the ‘block’ signal his proximate yet peripatetic wanderings. Additionally, his collection practice is shaped by this spatial logic.

Structure informs Washington’s art and its easy associations with sculpture. The structural orientation of his art brings to mind his decades long tenure as a set designer for NBC studios, where he gained renown as a master of modelling and fabrication[14]. Thus modelling design appears in his sculptural works which tend to have sound internal structure. I am reminded when considering the skyward movement of his art-works that there is a spatial-temporal reference to Watts, Los Angeles, particularly in Simon Rodia, and his site-specific construction, known as the “Watts Towers”. Washington has named Rodia’s towers as an early and potent influence on his art. The “Towers” were constructed between 1921-1954, in an active process of building, demolition, and rebuilding. Jazz musician Charles Mingus, who lived in the Watts neighborhood, described the towers in his memoir as “three masts, all different heights, shaped like upside down ice-cream cones.”[15] This sense of laterality is still evident in Washington’s art. In addition, Rodia used clay tiles that both strengthened and embellished his structures. The specific metallurgical materials that Washington assembles draw an aesthetic resonance to Rodia.

[1] Lorna Tate (director). Tossed and Found: An Artist’s Creative Journey.

[2] See Timothy Washington interview in Lorna Tate. Ibid.

[3] Hortense Spillers. “Moving on Down the Line: Variations on the African American Sermon”. Black, White and In Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture. 2003. pp 251-277.

[4] Washington in Lorna Tate. Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Salim Washington. “All The Things You Could Be By Now: Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus and the Limits of the Avant-Garde”. Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies eds. Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, Farah Jasmine Griffin. 2004. pp 27-49

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Hortense Spillers. “The Idea of Black Culture”. CR: The New Centennial Review, Vol. 6, No 3 (Winter 2006): pp 25.

[13] Timothy Washington in Liz Gordon. Diverted Destruction 6. Los Angeles.

[14] Lorna Tate. Ibid.

[15] Charles Mingus. Beneath the Underdog. Canongate Books, 1998.