Joy Revolution

I used to think there was a need to provoke, to attack religion, and the generals. And then I understood that there is nothing more shocking than joy. — Niki de Saint Phalle

Installation Views

Artwork

Niki de Saint Phalle, Guardian Lions, 2000

NIKI DE SAINT PHALLE: JOY REVOLUTION

It is with great joy that Salon 94 announces a major exhibition of works by Niki de Saint Phalle (1930–2002) to inaugurate our new building on 3 East 89th Street. Gathering important historical works from the Niki Charitable Art Foundation, alongside private collections, the exhibition ranges from rare maquettes to classic monumental Nanas, works on paper, and archival film, and includes rarely-seen, late mechanical paintings and mosaic furniture.

The exhibition celebrates the political and historical context of Saint Phalle’s practice and explores the artist’s philosophy of radical joy—a core concept of her utopic vision of an egalitarian matriarchal society. Long before anyone labeled her a feminist artist, Saint Phalle assembled symbolically charged figures who precociously embodied revolutionary gender politics.

“I called my first museum exhibition with the Nanas ‘Les Nanas au Pouvoir.’ [1] For me they were the symbol of a happy, liberated woman. Today, nearly twenty years later, I see them differently. I see them as the forerunners of a new matriarchal epoch.” [2]

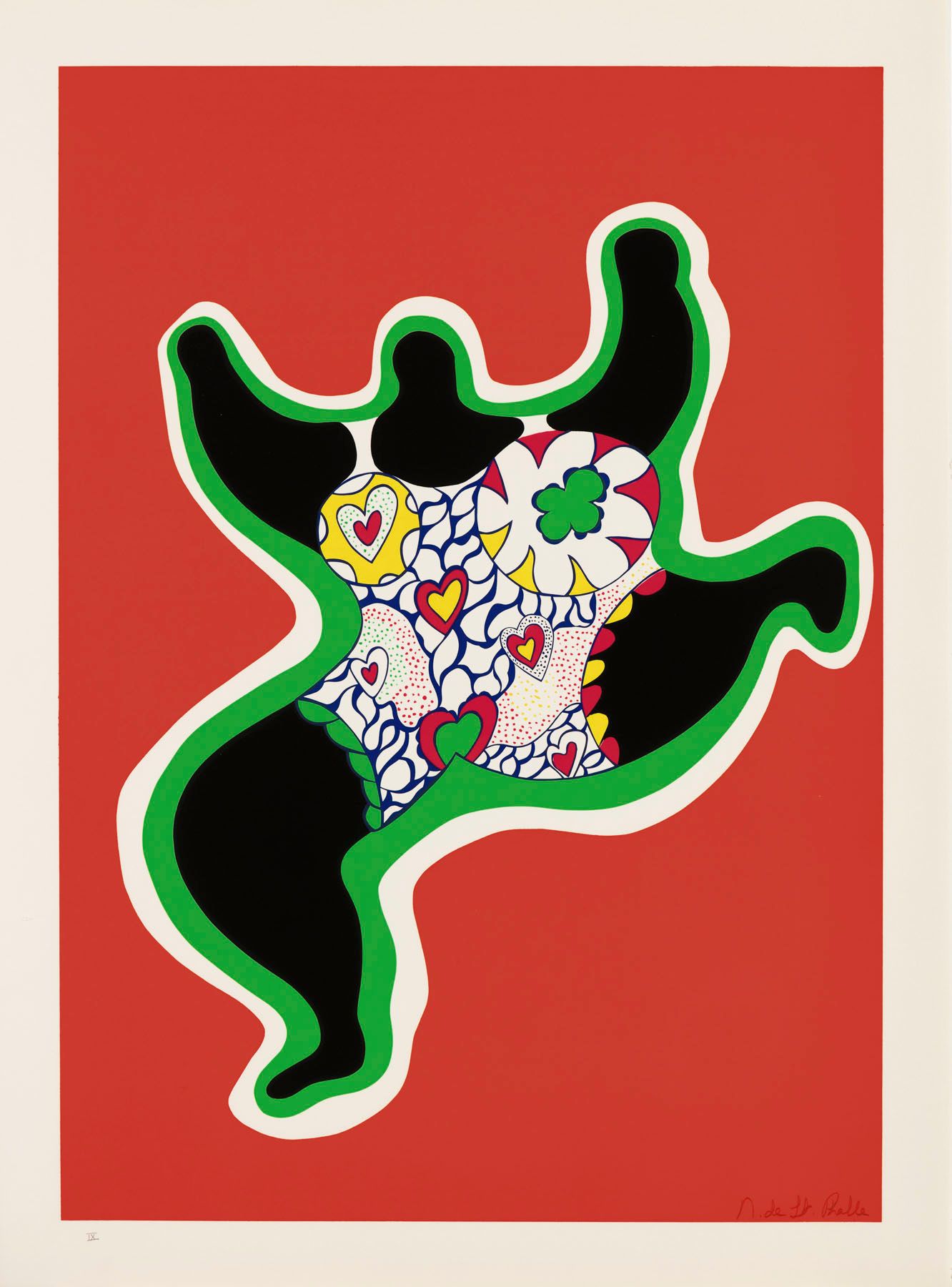

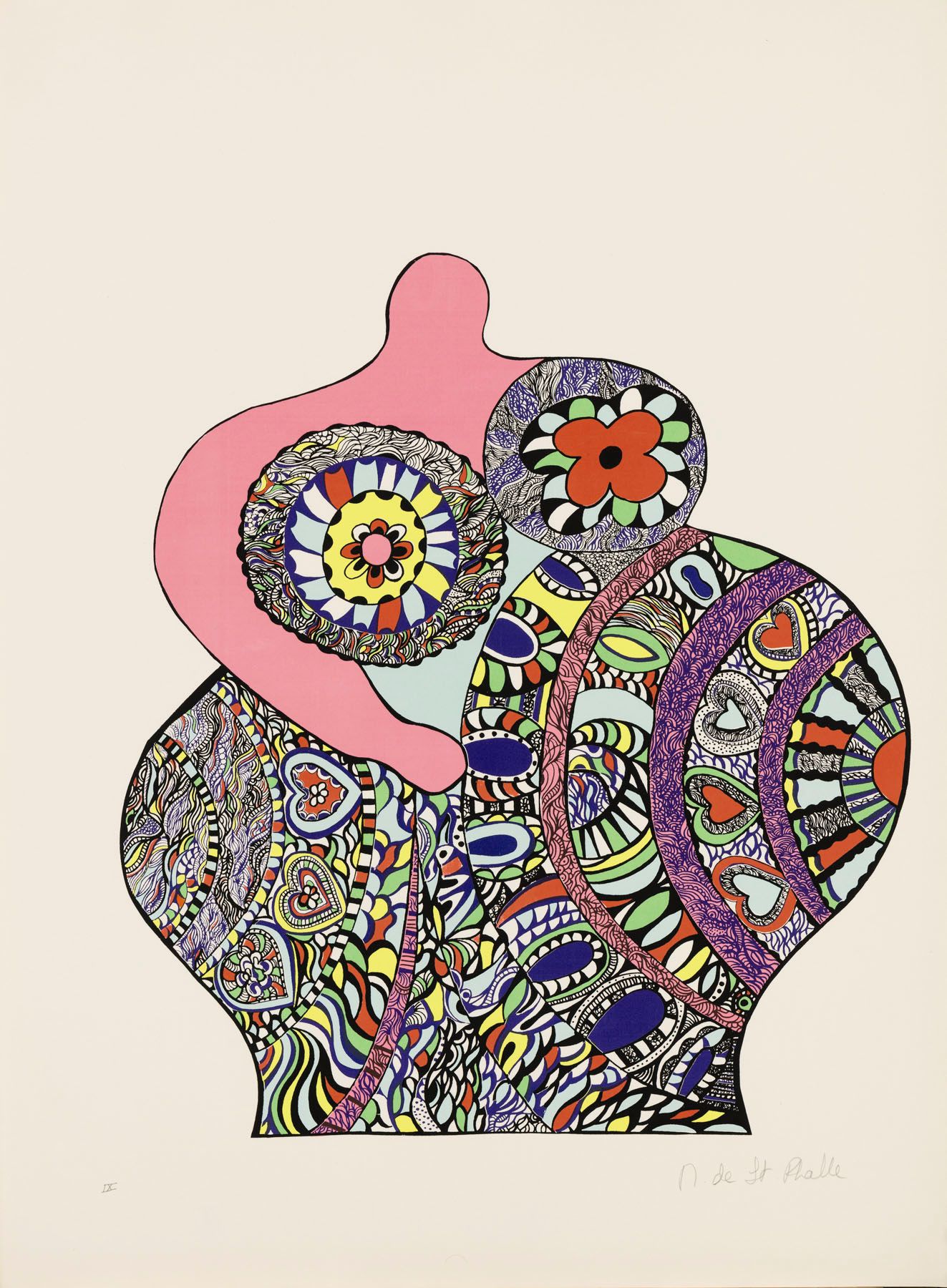

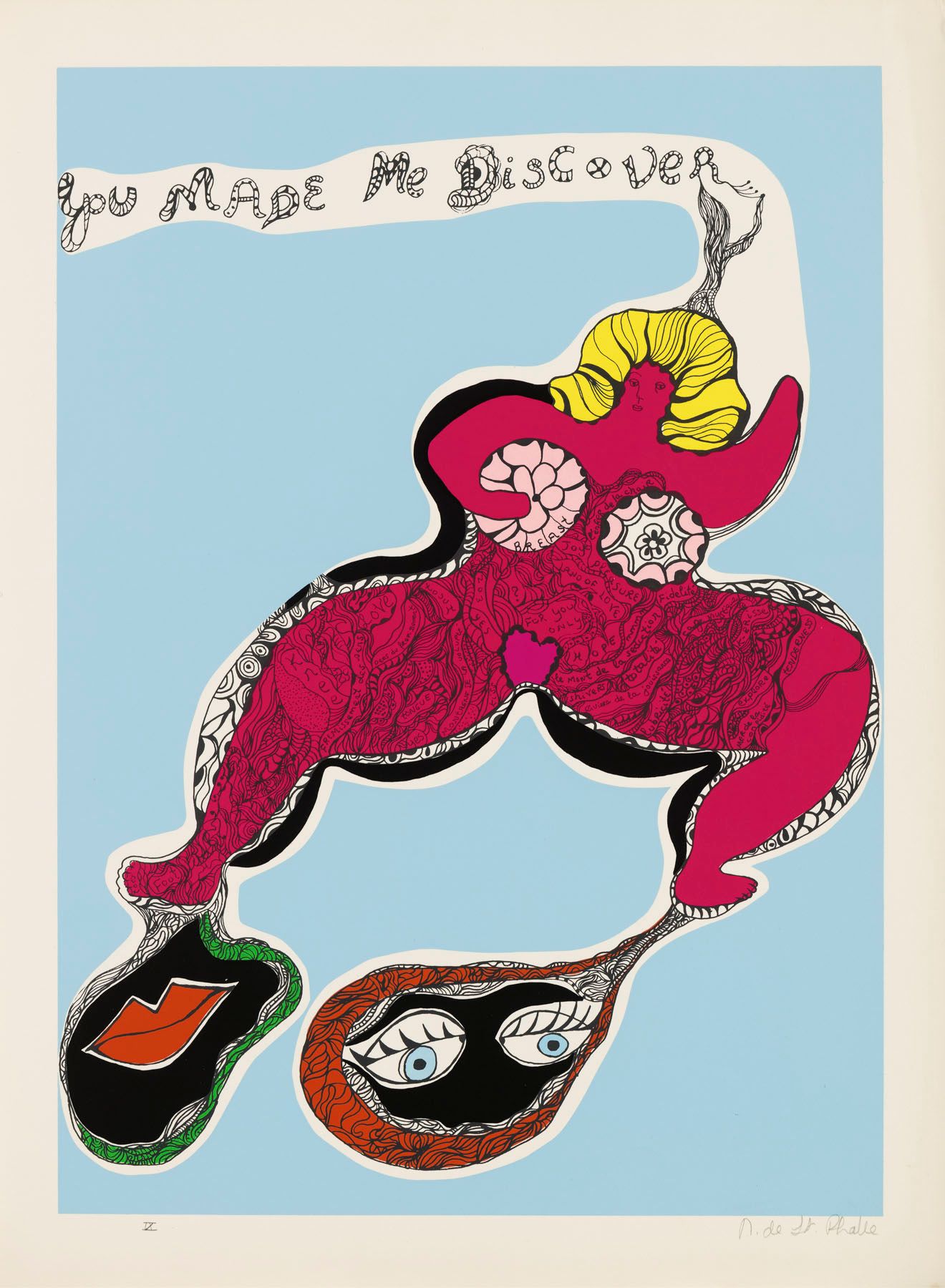

Throughout her career, Saint Phalle forged a sculptural pantheon of empowered womanhood. The Nanas came to be understood as emblems of women’s liberation and also became Saint Phalle’s brand, obscuring the more complex meanings behind their jubilant forms.

Her initial figures took the form of monstrous archetypes—Brides, Mothers, or Goddesses—made from amalgamations of plastic toys, fake flowers, dismembered baby dolls, and more. Painted white, these figures were fraught and haunted, carrying burdens of centuries of unhappy obligation and limited by their assigned roles. Many of these assemblage figures became targets for Saint Phalle’s Tir (shooting) paintings. Pointing a rifle at her work, she would shoot at the canvases, which released the colors she had loaded inside the work as a symbolic conflation of her personal rage and her expansion of the field of performative painting.

The radically joyful Nana was born in 1964. Saint Phalle explained this dramatic shift to the Nana—the somewhat innocuous French slang for girls or “chicks”—in her life and her work: “After the shooting paintings the anger was gone, but pain remained, then the pain left and I found myself in the studio, making joyous creatures to the glory of women.”[3]

In 1967 these “joyous creatures” grew in stature and scale as Saint Phalle presented monumental Nanas, and the wild animal sculptures that often came with them, alongside a forest of living trees rising in the height of the Stedelijk Museum galleries. Marking Saint Phalle’s lifelong practice in outdoor, public space, the concept of the garden continued throughout her practice as a space for growth and freedom.

Niki de Saint Phalle, Golem, 1971–1972, Jerusalem

Playground

The Guardian Lions, made two years before her death in 2002, greet visitors as they enter our new entrance gallery. Emblematic of her public sculptural practice, the paired works were conceived by the artist for public gardens with the expectation that they would be climbed and played upon by children. They refer to the sculptures of lions found in front of buildings and structures in Western, Asian, and African cultures, and use her trademark mosaic technique that combines glass, brightly colored beads, ceramic tiles, and sandstones that Saint Phalle developed while building the Tarot Garden (1979–2002) and Noah’s Ark (1995), a playground/sculpture park in Jerusalem. The original maquette of this collaboration with the architect Mario Botta will be on view.

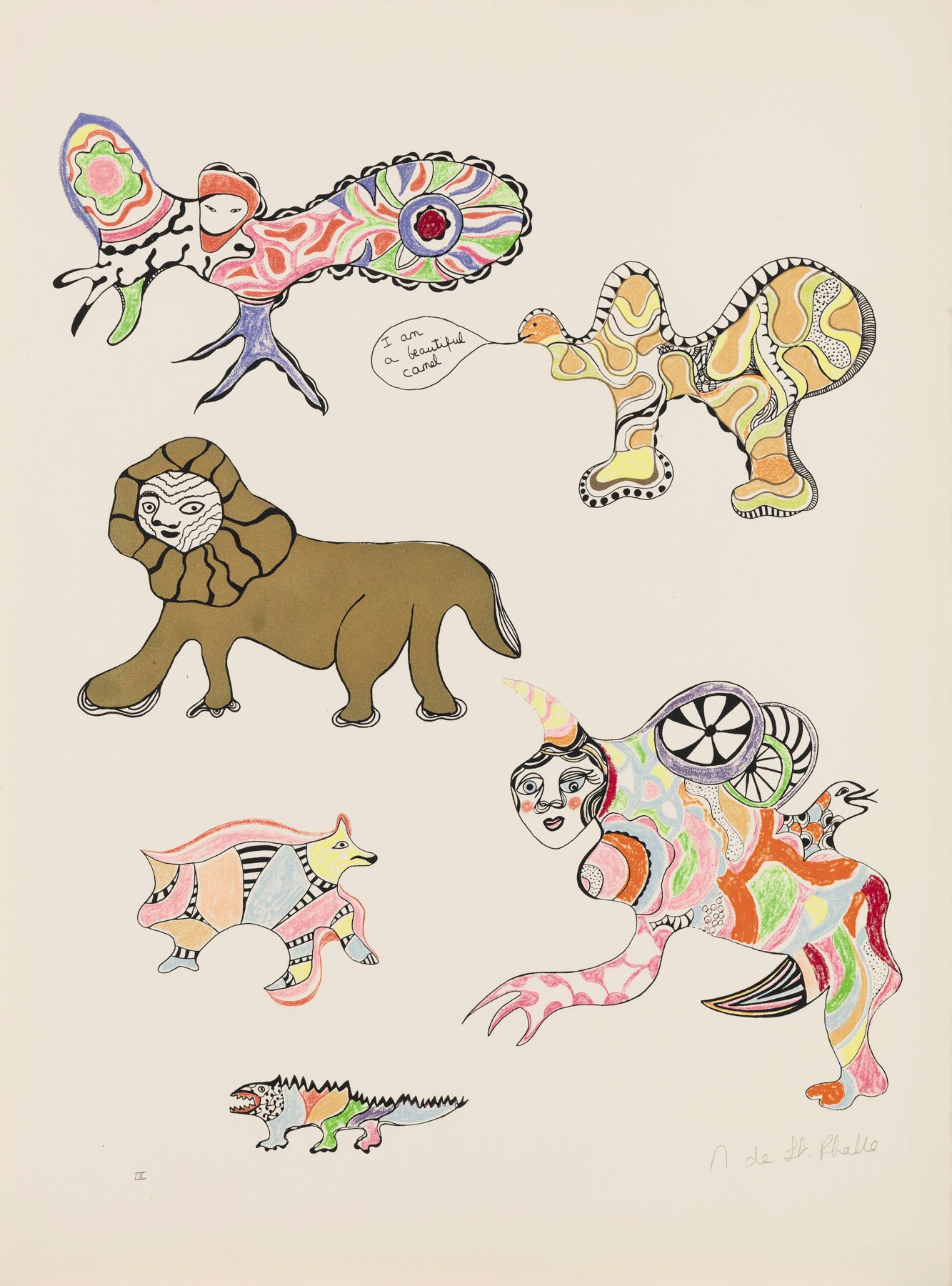

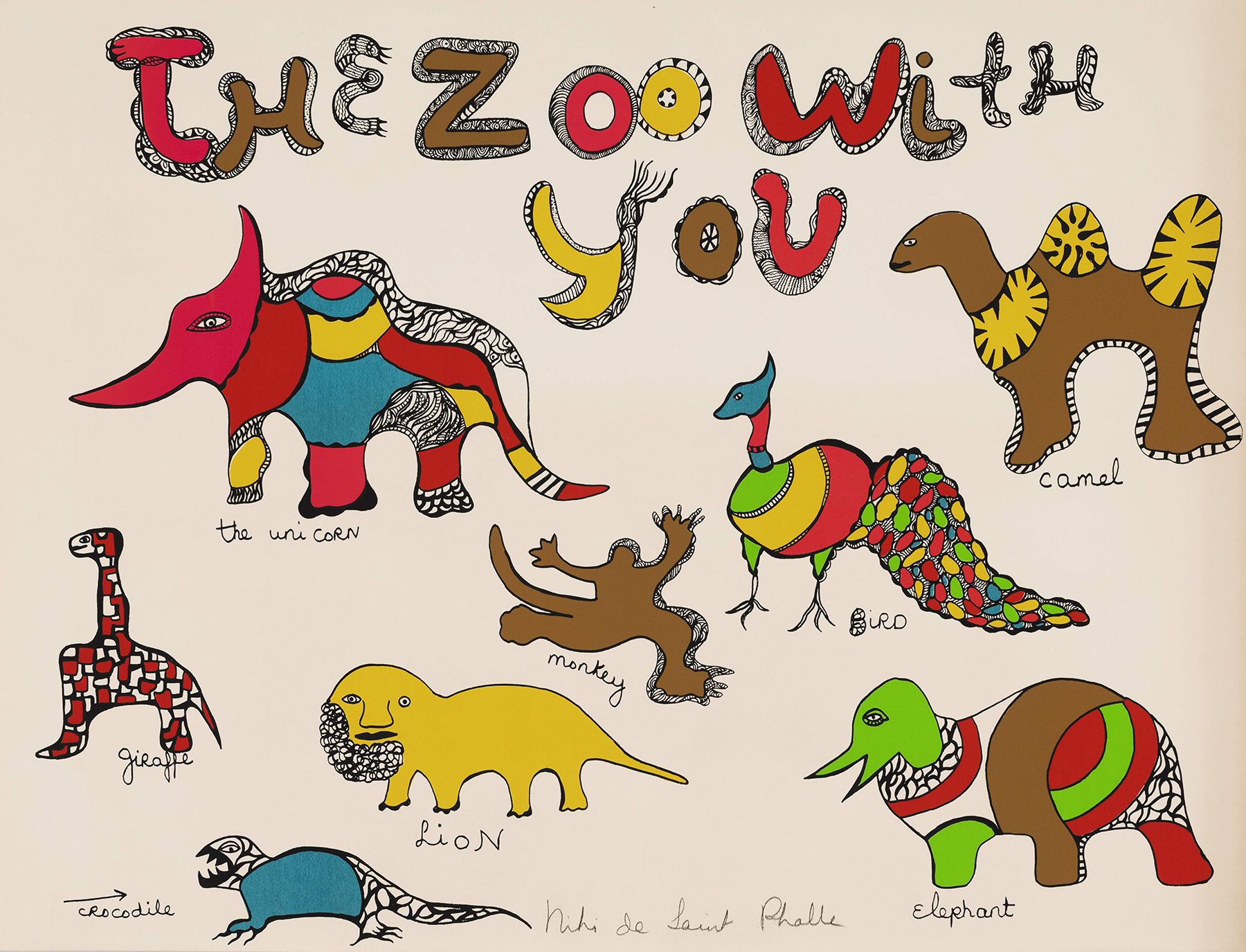

Animals and mythical creatures—popular, accessible, and inclusive figures that cut across cultural and social divides—recur frequently in Saint Phalle’s oeuvre. Inspired by a range of literary, religious, and mythological sources, the menagerie of real and fantastical animals is an integral part of the philosophy that undergirds every aspect of Saint Phalle’s life work—animals coexist equally with humans, carrying their own symbols and stories. For the artist, play represented a subversive force in society, a moment when power roles could be reversed, and serve as portals to the depths of imagination.

Saint Phalle was a central figure of the postwar avant-garde and the only woman in the Nouveaux Réalistes group (founded in 1960; Saint Phalle joined a year later.) She stood apart from her peers in her rejection of elitist theories and rarified forms: she was well aware that her animals of later years were complete anathema to art theorists and critics of the time and generally considered not worthy of elevation to modern art. “I like the fact that I am able to say something on a very immediate level,” she said. “So much art today has become tied up with ideas, with philosophy, with the abstract, and a lot of people feel excluded from it because of the impoverishment of the image. Nobody is excluded from my work." [4]

Saint Phalle hoped to transform public space with her sculptures; hers was a generous and transformative conception of art as public service. The formal origins of Saint Phalle’s public works hark back to her exposure to visionary architecture experienced as a young person. “For me the most important people are the ones who made Bomarzo, they’re Gaudí and Le Facteur Cheval, they’re the Watts Towers in America and the cathedrals of Europe.” [5] All of Saint Phalle’s public works entwine the magic of these aesthetic antecedents with the imposition of her ambitious scale.

One of the only women artists to imagine monumental public sculpture and architecture from the mid-60s onward, Saint Phalle’s public works can be studied as feminist and political. “I want to have the delusion of grandeur to prove that a chick can make the most important things of her time.” [6]

Niki de Saint Phalle, Gwendolyn, 1966–90

Joy Revolution

“I thought beforehand that to be provocative, you had to attack religion or generals. I realized that there was nothing more shocking than joy.” — Niki de Saint Phalle in an interview with Otto Hahn, 1968

Bringing together a selection of her most iconic large-scale figurative sculptures of the 1960s, the second-floor Stone Room is focused on the figure of the Nana. Larger than life in scale, such seminal Nana sculptures as the pregnant goddess Gwendolyn (1966), Black Dancer (1967), and Peril Jaune (1969) anchor this presentation. Directly quoting the original exhibition scenography of her 1967 Stedelijk exhibition, this trio of Nanas will be arranged amid plants and trees that transform the gallery’s sumptuous piano nobile into a garden. In this mise-en-scène, these grand-dame Nanas seem to play and frolic as if in a prelapsarian Garden of Eden as Saint Phalle originally intended. As this restaging of the Stedelijk Museum show scenography reminds us, the garden trope runs throughout Saint Phalle’s oeuvre—as a metaphorical and physical site for her vision of a matriarchal society.

Inspired by ancient art and mythological characters, the Nanas became positive counterexamples of the oppressed reality of most women. One must remember that in 1965 in France, women were not allowed to open a bank account or apply for a job without the approval of their husbands.

Saint Phalle, who had grown up in the United States and showed in New York during the early sixties found an American muse in her intimate friend, Clarice Rivers, the wife of the artist Larry Rivers. Rendered by Saint Phalle, Clarice’s pregnant body and voluptuous forms echo archaic fertility goddesses and suggested newfound sexual freedom and a different relationship to birth. Clarice was also the inspiration for Hon (1966; “she” in Swedish)—the nine-meter-tall Nana-cum-house-sculpture-installation that the public could walk into vagina-first.

Eschewing realism for a Euro-pop sensibility, the Nanas were painted in playful line drawings and exuberant multicolor patterns or primary palettes of white, black, yellow, and blue. Some portrayed her friends; others were vehicles for Saint Phalle’s political convictions, whether paying homage to civil rights icon Rosa Parks (My Heart Belongs to Rosy, 1967) or contesting racist stereotypes during the Vietnam War and exploring the truths of female freedoms (Le Peril Jaune, 1969).

In 1966 Saint Phalle was commissioned to create a Nana stage set for a contemporary take on Aristophanes’ Lysistrata. Saint Phalle interpreted the story of the women of Athens and Sparta who form an alliance to stop the war. The play, written in 411 BCE, spoke to the artist, not only in terms of its theme of women banding together to free themselves from men and defeat them, but the relevance of its peaceful message: “The play was in line with my intention to get people thinking [about] Vietnam.” [7]

Inside L’Impératrice (The Empress), Tarot Garden, Garavicchio, Italy, 1979–2002

Inside the Nana Maison

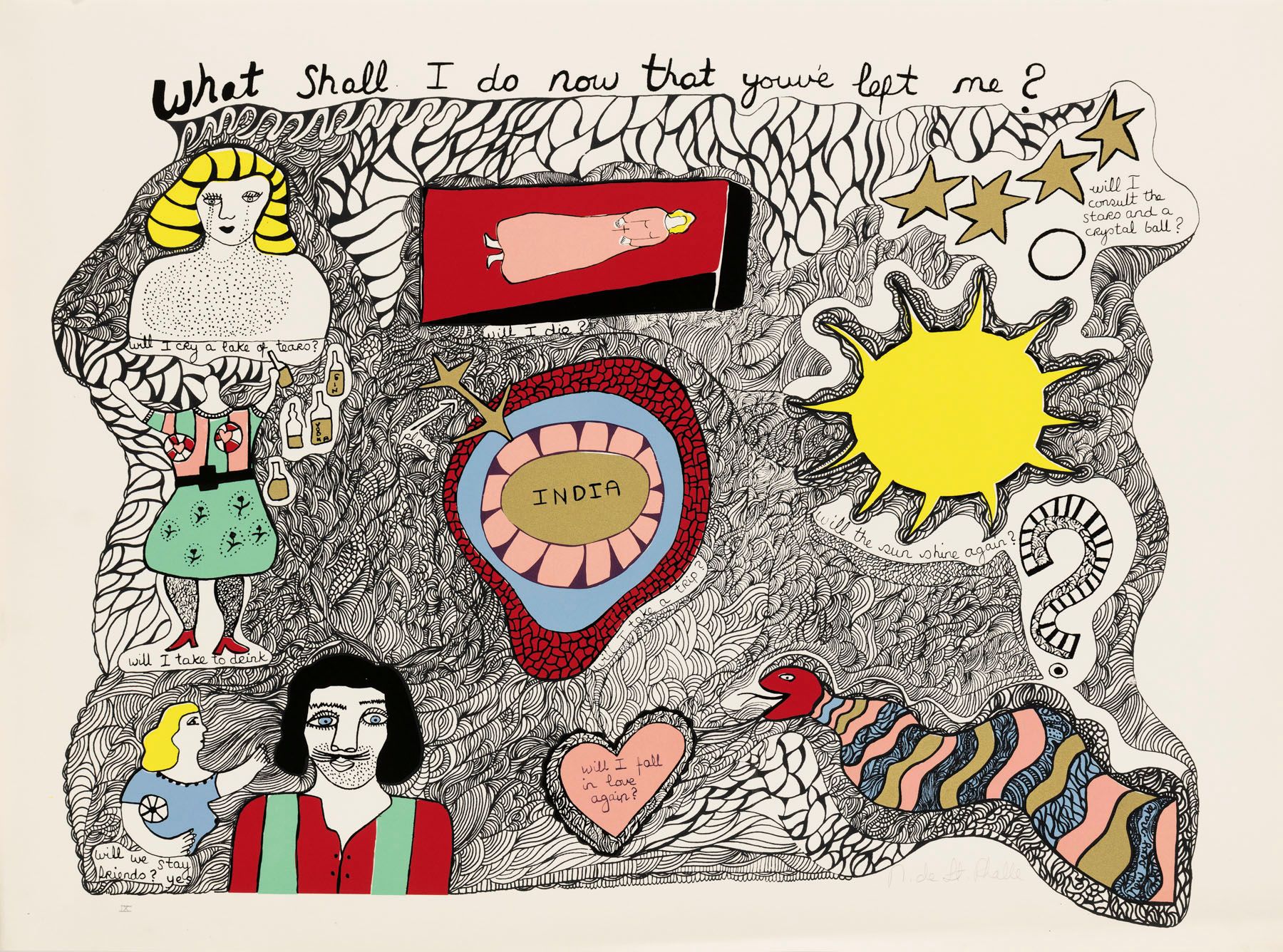

The last gallery merges together the artist’s art and life. If the figure of the Nana was born as Saint Phalle’s signature high art motif, it was most fully realized in the manifold ways the artist applied her aesthetic and philosophic concerns to real life: architectural structures, functional objects, domestic scaled works, plans, and autobiographical prints.

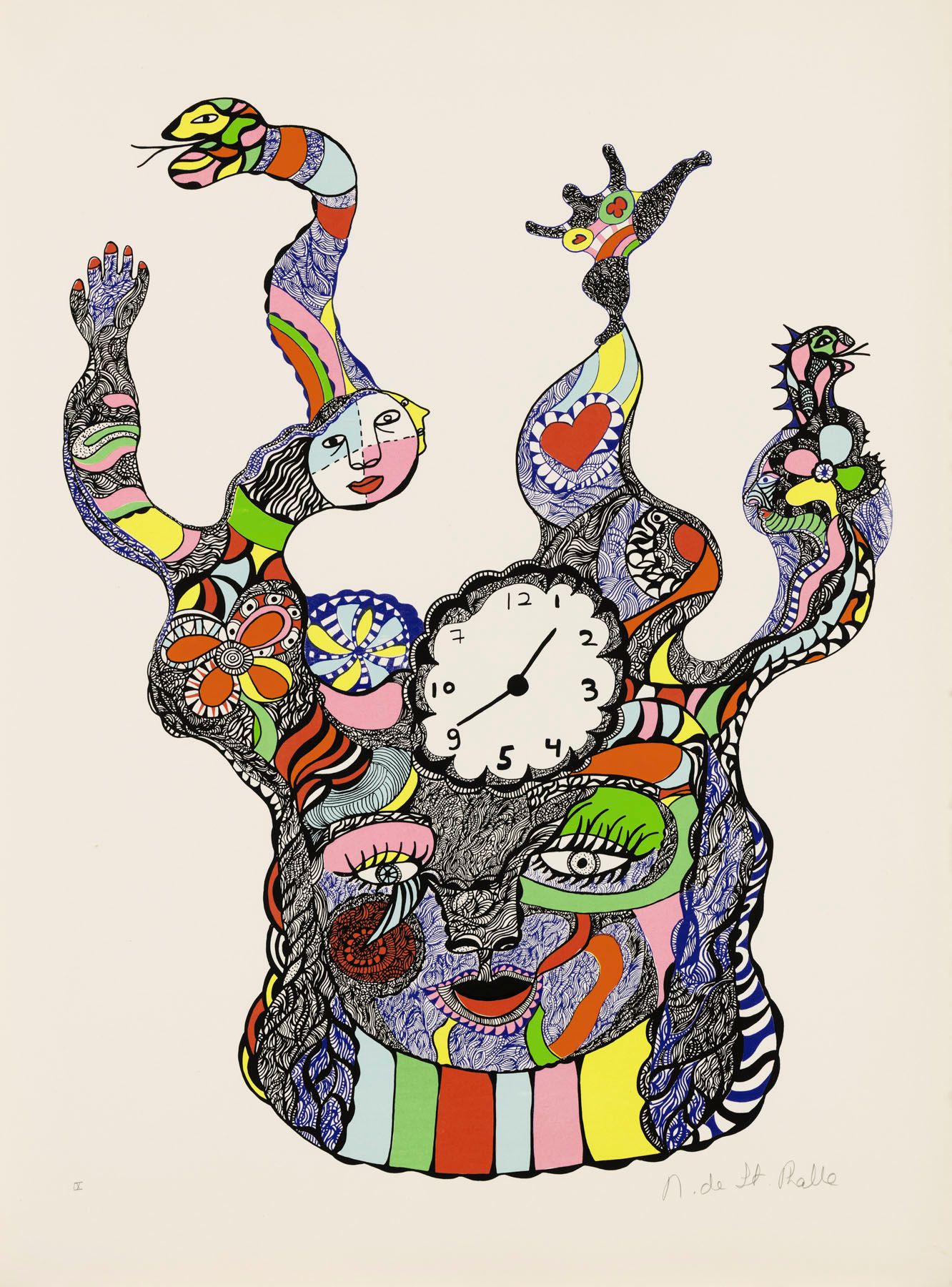

Movement and dance were the central means by which Saint Phalle brought her otherwise stationary sculptures to life. The third-floor gallery explores this theme—including a film documenting the legendary 1966 L’Éloge de la Folie, an avant-garde ballet featuring several of Saint Phalle’s Nanas. On a much smaller scale, her Nana Machines carry the DNA of such theatrical collaborations and continue this theme of life-giving movement. The 1971 Nana Brochette (or Nana dansant avec Moteur) showcases a colorful female dancer figure made out of brightly painted resin. She is posed on one leg and her arms are aloft. She turns on a motorized welded metal pedestal made by Saint Phalle’s partner Jean Tinguely. Deploying his signature assemblage style, the dark metal has exposed wires, cogs, and machinery, which, when illuminated, transforms the stationary Nana to turn into a pirouetting ballerina.

In conversation with the current exhibition of Saint Phalle’s work at MoMA PS1, featured in this section are pivotal models of some of her most ambitious public works as well as those for unrealized utopic structures. In and of themselves magnificent miniature sculptures, these include Nana-shaped maquettes for the Empress structure and the Justice building from her Tarot Garden. These maquettes, alongside a number of functional objects, were also conceived as accessible editions, along with her eponymous perfume that was sold to support the creation of the Tarot Garden. Prefiguring the crossover commercial collaborations of contemporary artists like Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, and KAWS, Saint Phalle explained, “I spend all the money I make from my perfumes and sculptures here on my garden…I am my own patron. I live my project day to day…my only limits are my strength and my financial means.”[8]

The duality of utopian and utilitarian is a thread that runs throughout this part of the exhibition. A revelatory drawing-collage depicting her Nana Dream House (1969) prefigures actual architectural projects that soon followed. The handwritten caption in the drawing reads, “I am the Nana dream house. I am twelve feet high and twelve feet wide. Inside of me you can put anything you wish—a bar, a bed, a library, a brothel, a chapel. I am an adult’s playhouse. A refuge to dream in.” Saint Phalle did build actual versions of the Nana Dream House, as well as other inhabitable structures that she filled with specialized furniture that she made. Starting in 1979 and for over twenty years, she lived inside the Empress figure of her Tarot Garden in Garavicchio, Italy as she worked on completing the 22 architectural sculptures. A primary example of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the interior of the Empress was conceived as a totalizing environment of her own making—dining room, kitchen, bedroom, and bathroom entirely covered with mosaics and outfitted with Saint Phalle–designed furnishings.

Saint Phalle also worked on a domestic scale; this section of the exhibition includes a table, chairs, a vase, and a lamp sculpture. Of particular note is Saint Phalle’s mosaic table, Monastère Table, designed as a dining table for her living quarters inside the Empress. Above the table hangs a chandelier Jean Tinguely made for Saint Phalle; next to it sit chairs that Saint Phalle commissioned from the artist Pierre Marie Lejeune.

As her biographer Catherine Francblin wrote, Saint Phalle’s work aimed to bring her public together. She wanted to bring life to her work and activate it. Complaining of the bourgeois interiors of her collectors who hung lifeless art on their walls, she also created sculptures as furniture pieces. Art was to be touched and to provide a sense of wonder and joy. If one must sit on a chair every day, it might as well come covered in snake characters: a potential story, a potential conversation piece. The Monastère Table, covered in the same glass tiles that make up the walls of her apartment in the Empress sculpture at the Tarot Garden, seems to offer clues and a game. Also on view in Gallery 3 is Carrie Mae Weems’ self-portrait Niki’s Place, Mussolini’s Rome (2006), taken inside the Empress, looking at and being reflected in the mosaic mirror walls of Saint Phalle’s living room.

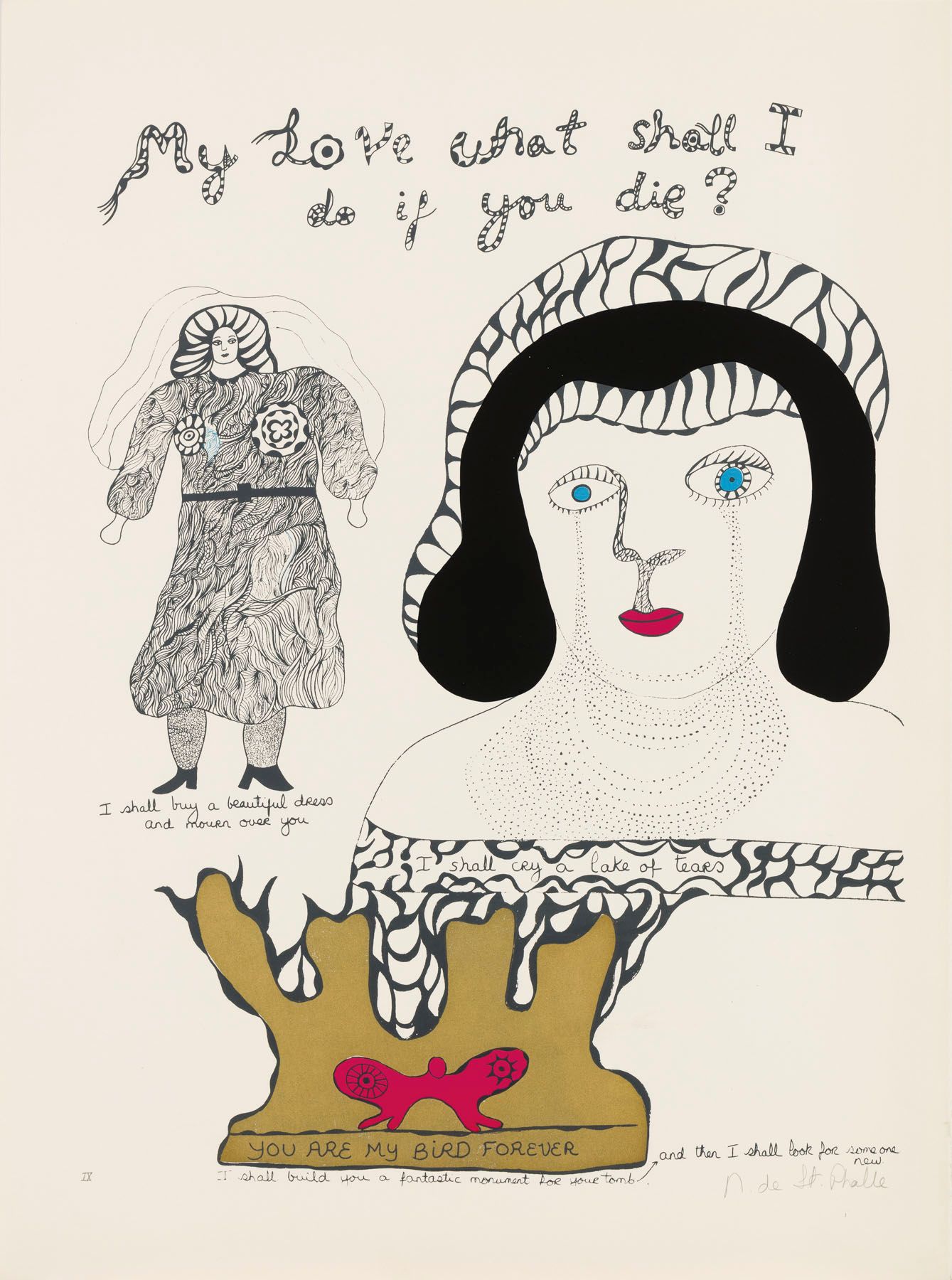

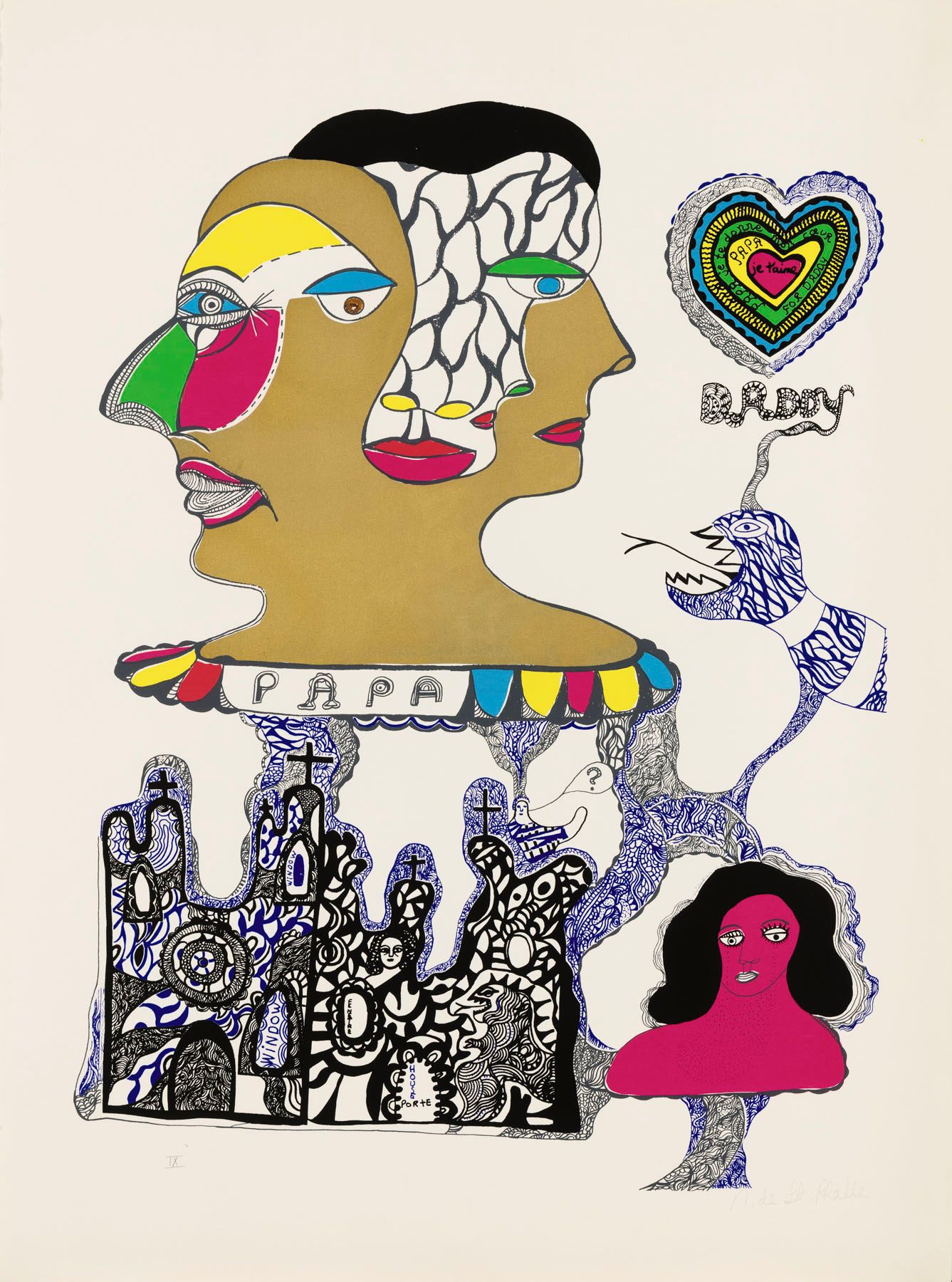

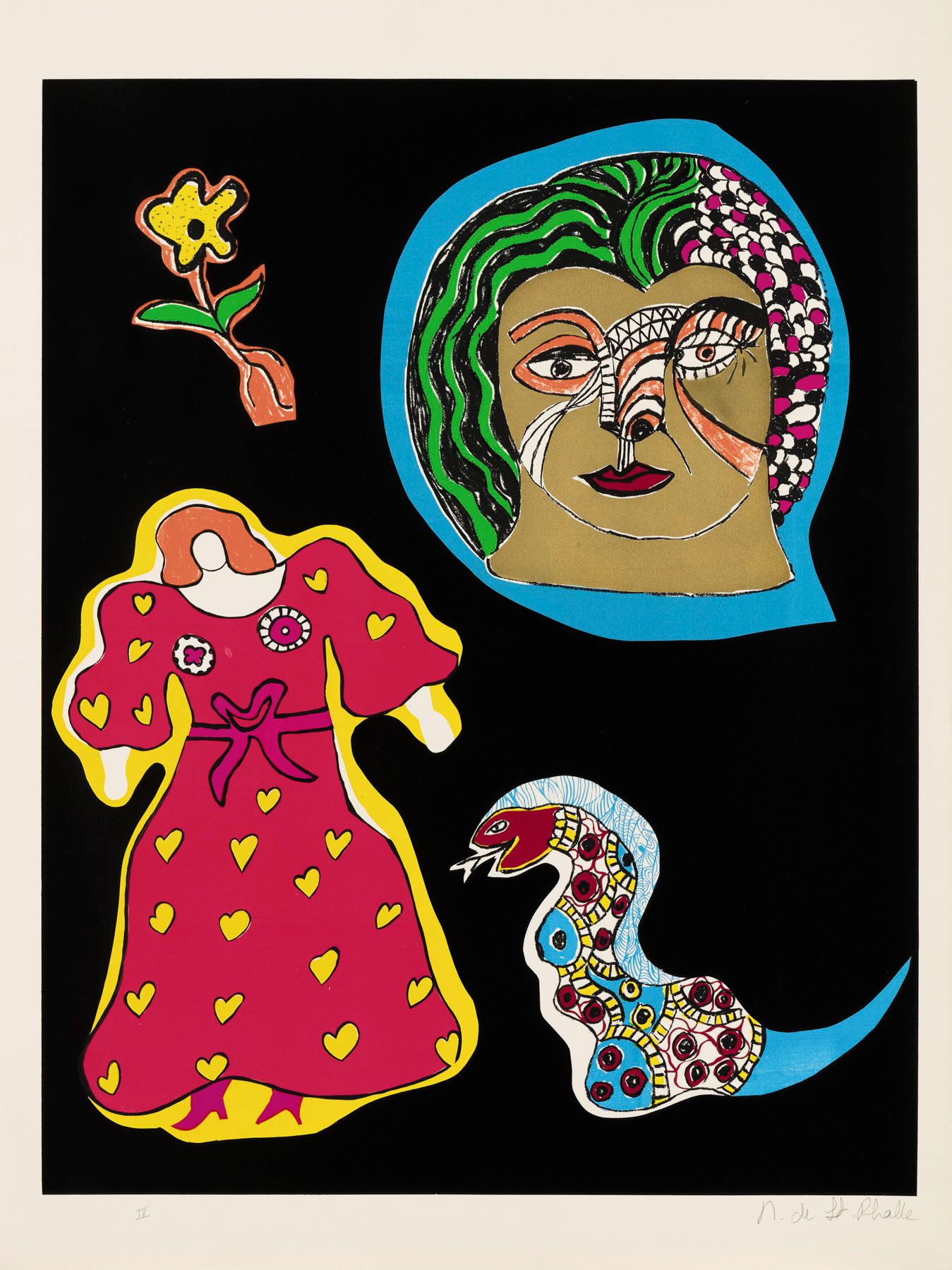

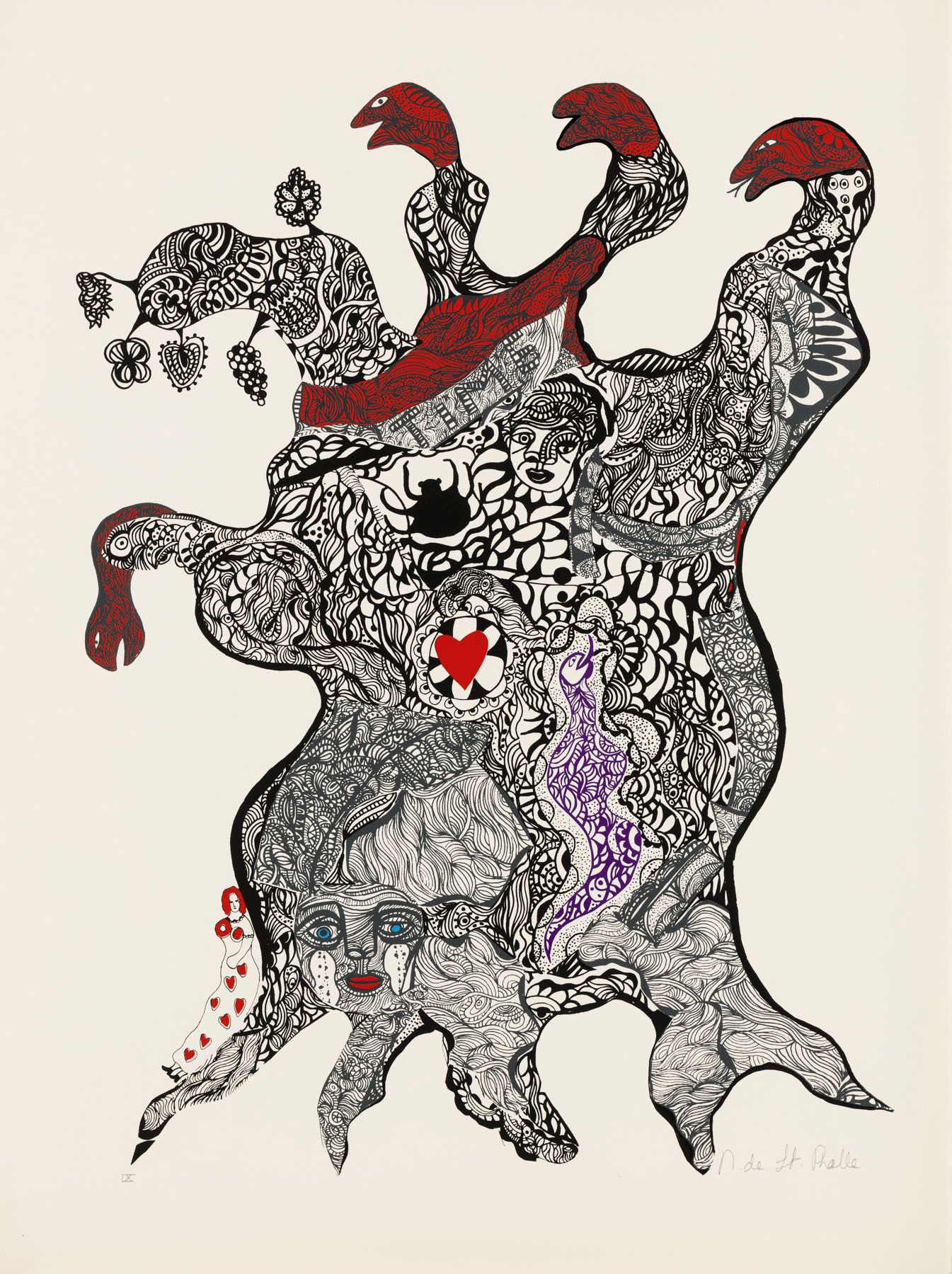

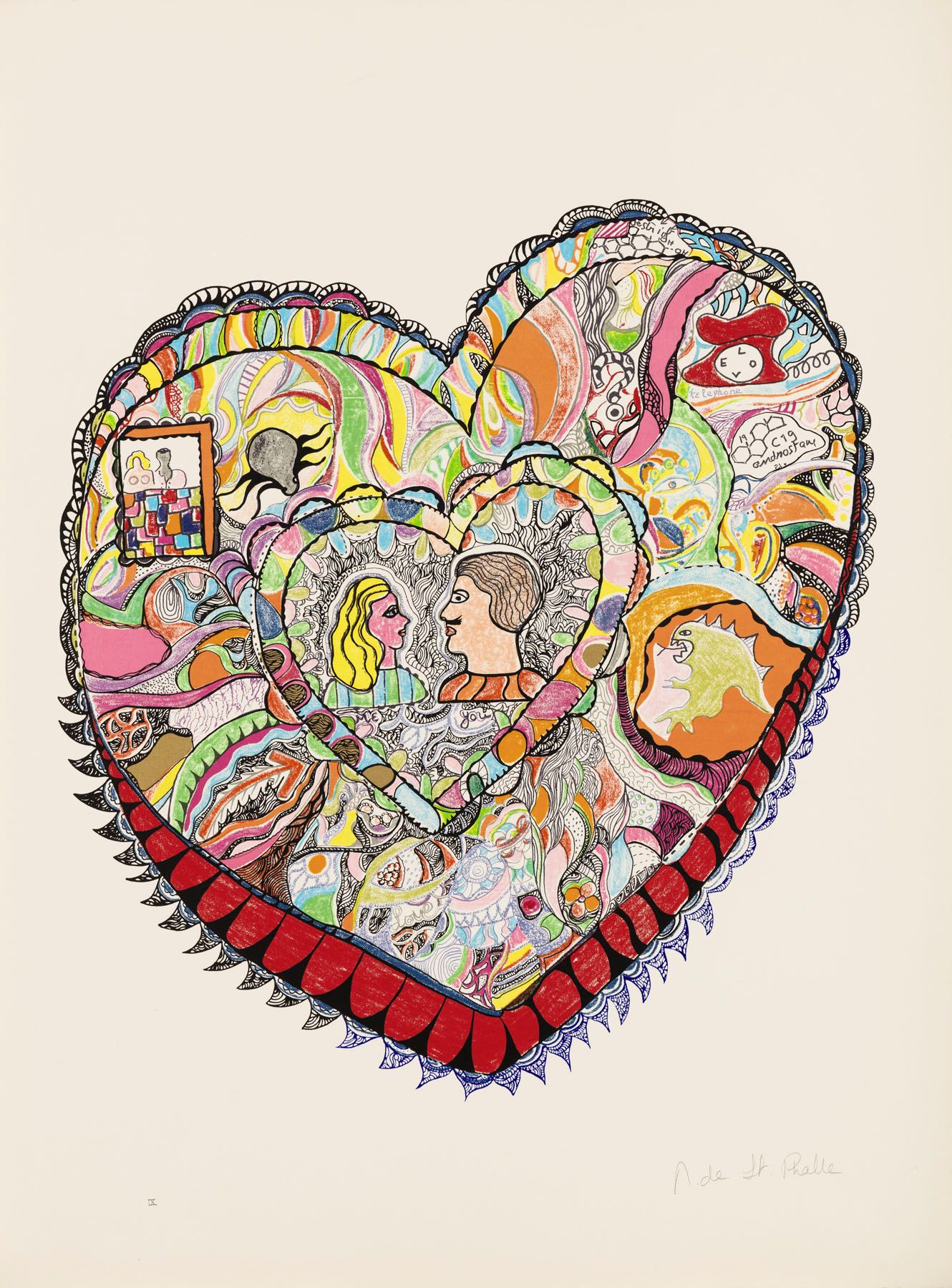

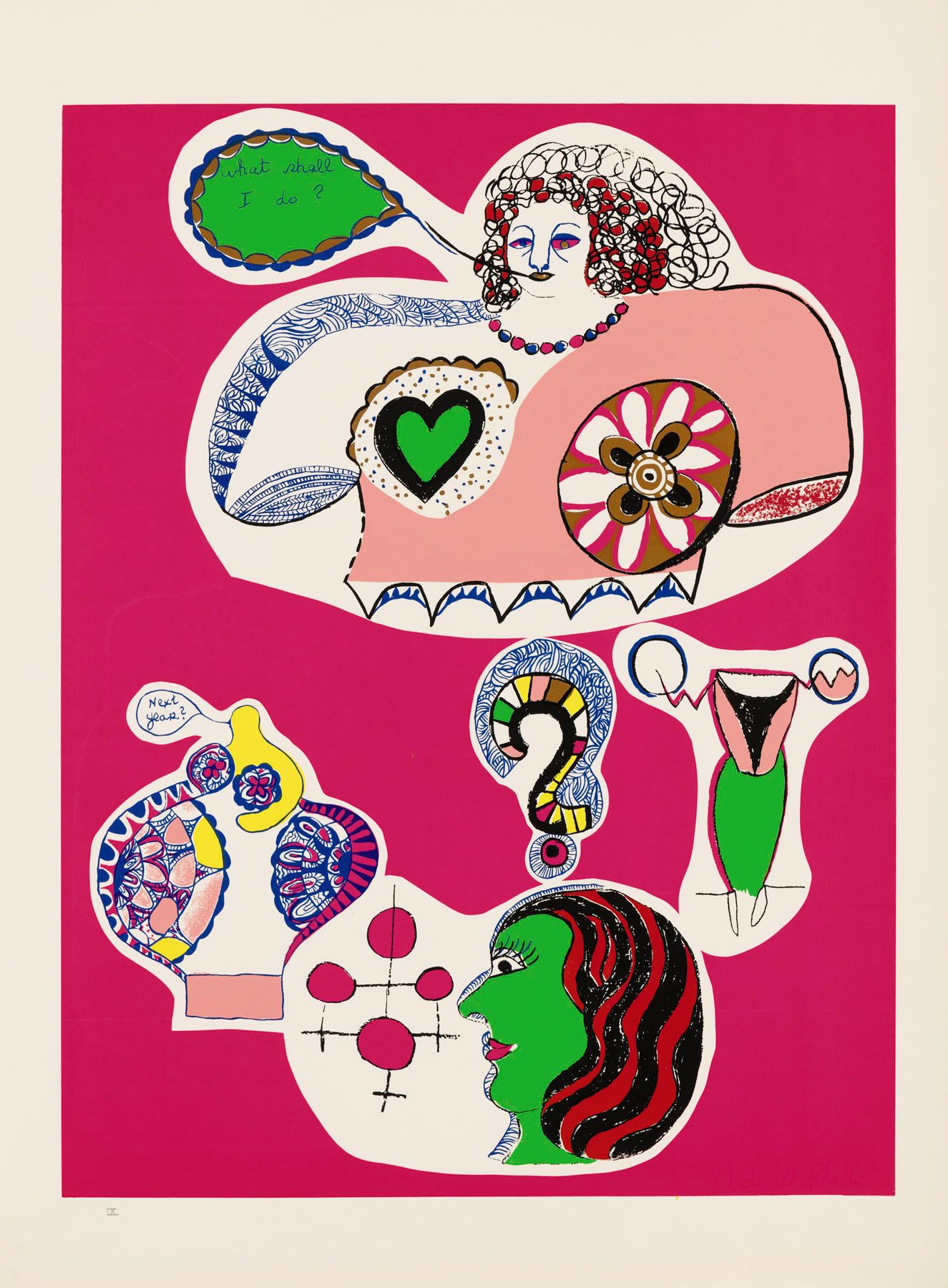

Niki de Saint Phalle, Nana Power, 1970

Telling her Story

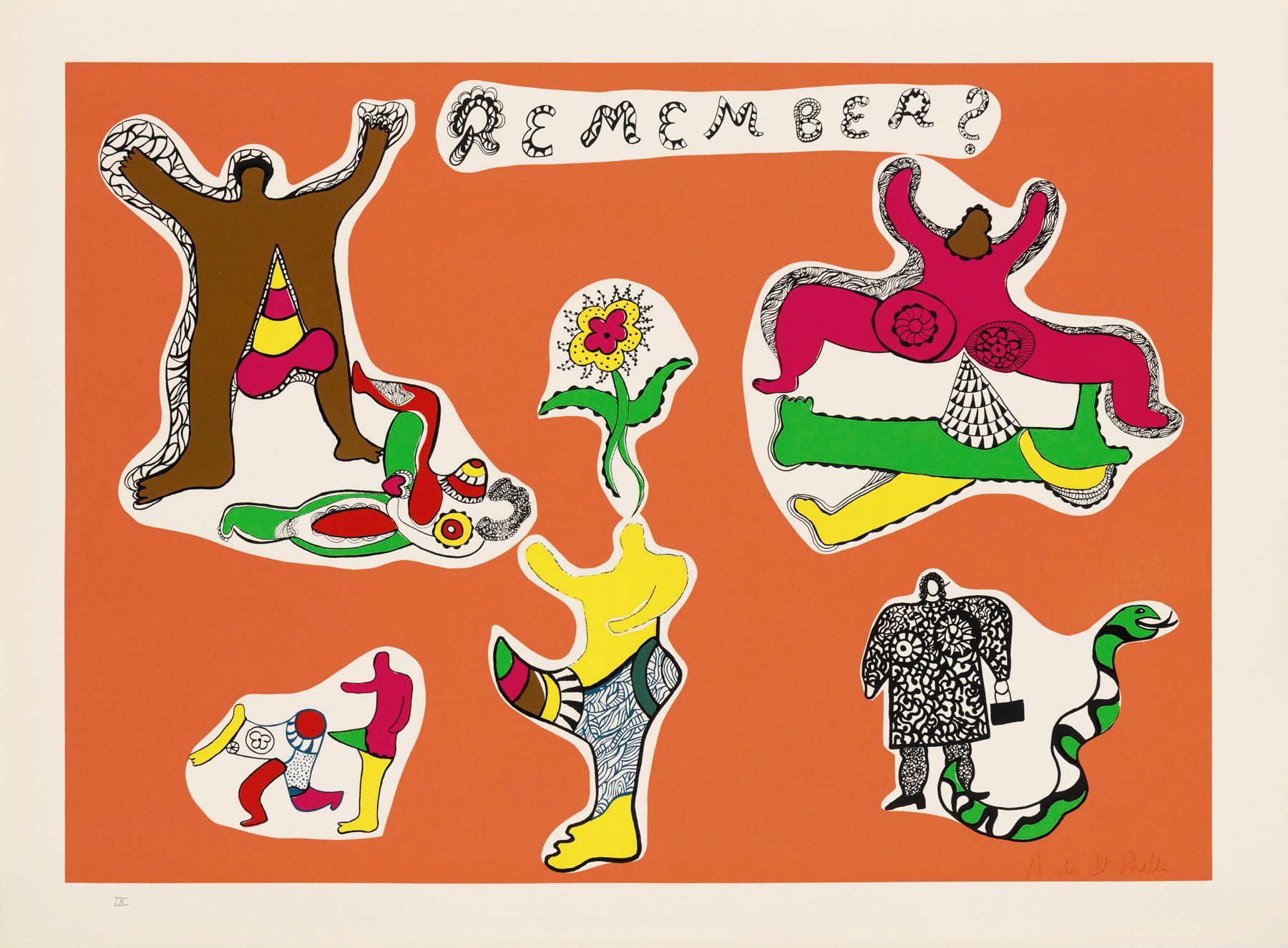

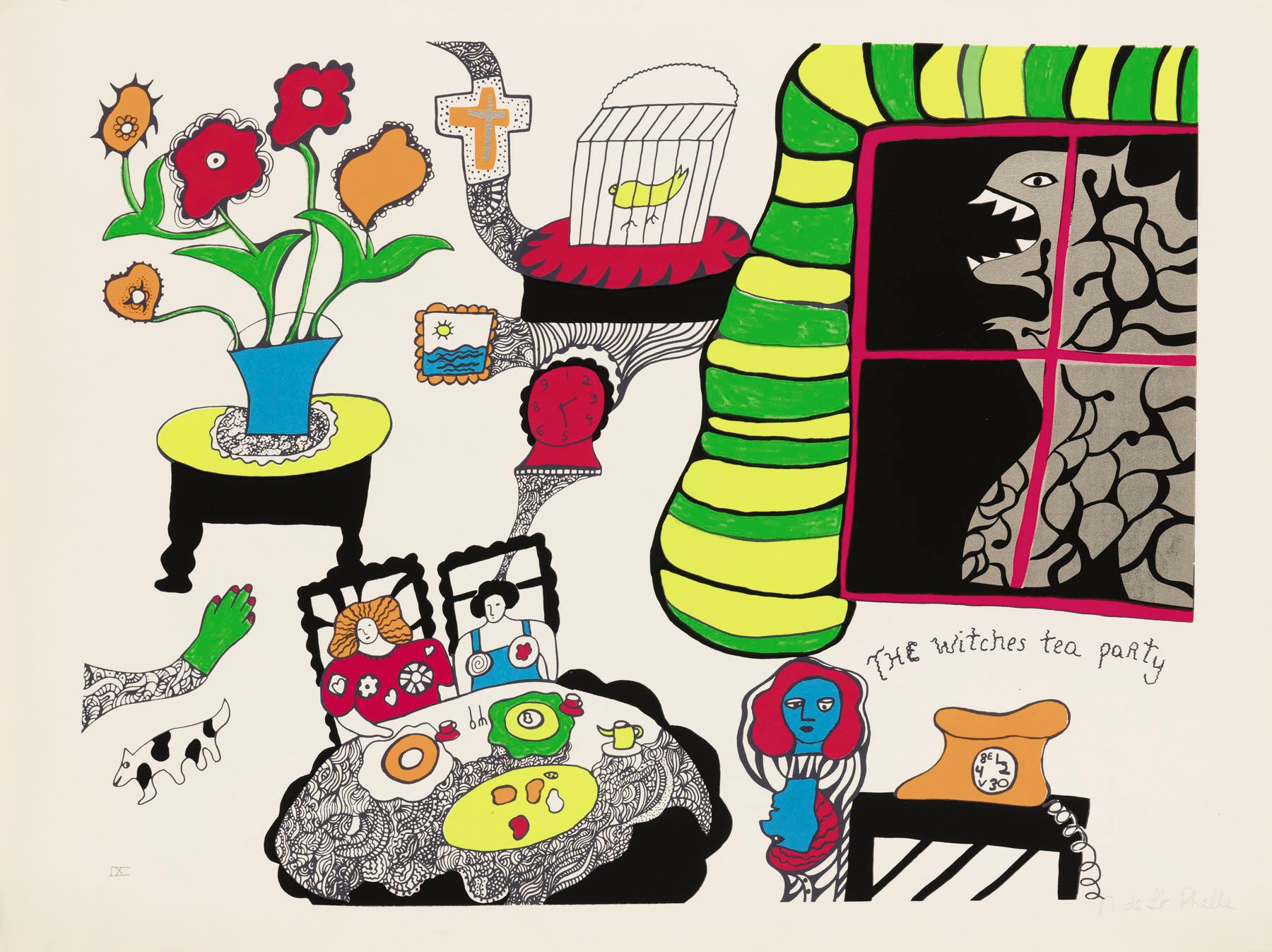

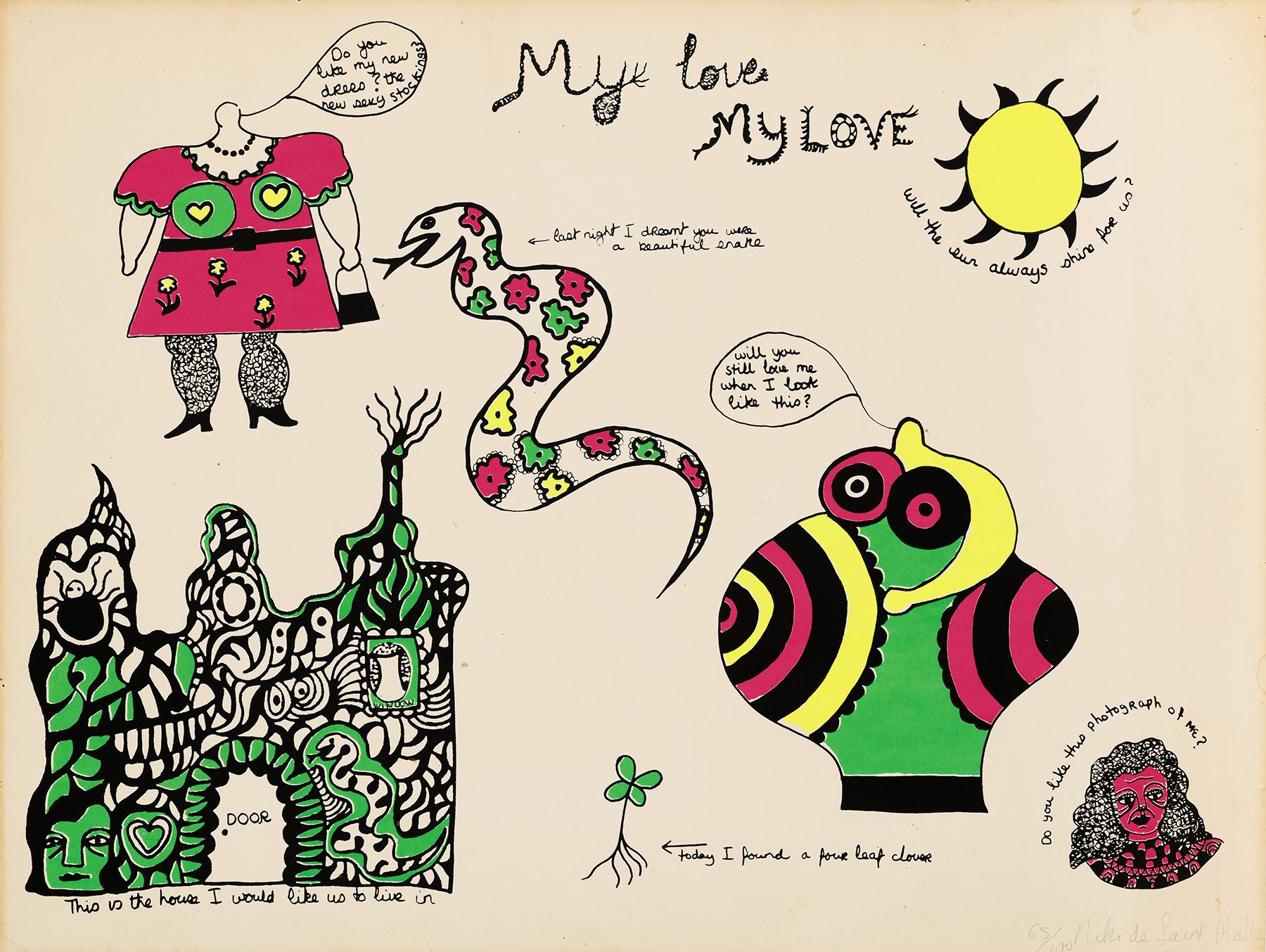

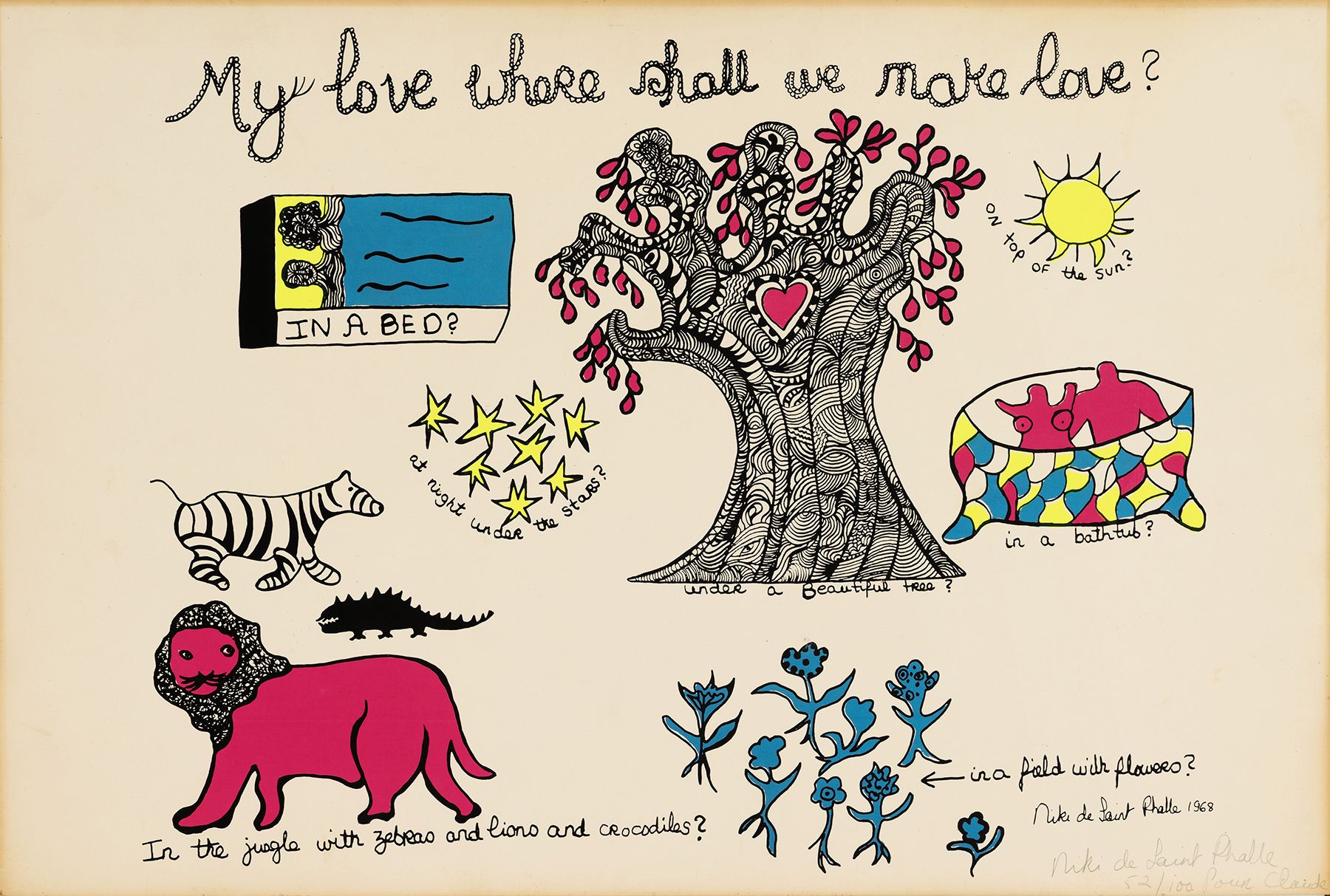

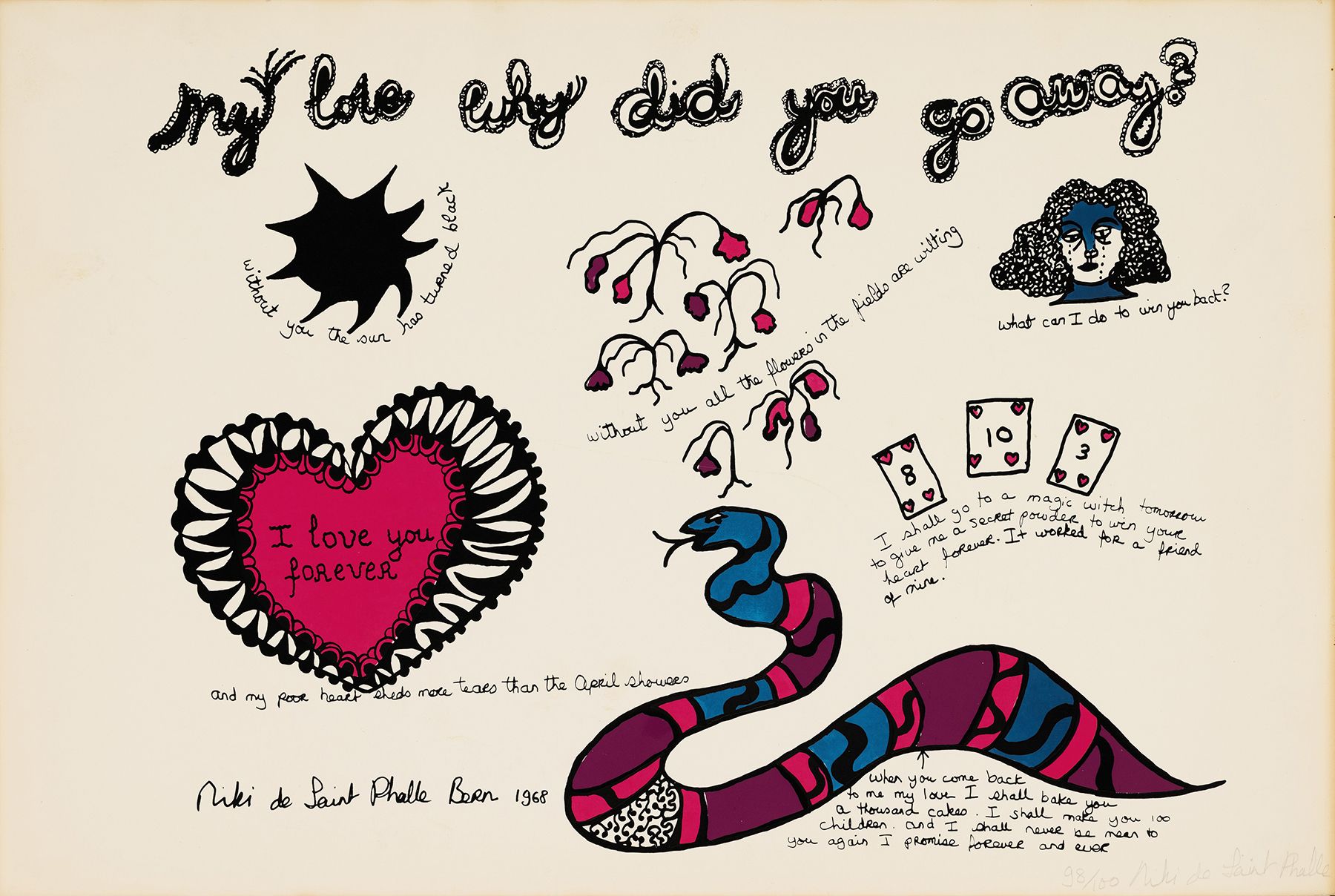

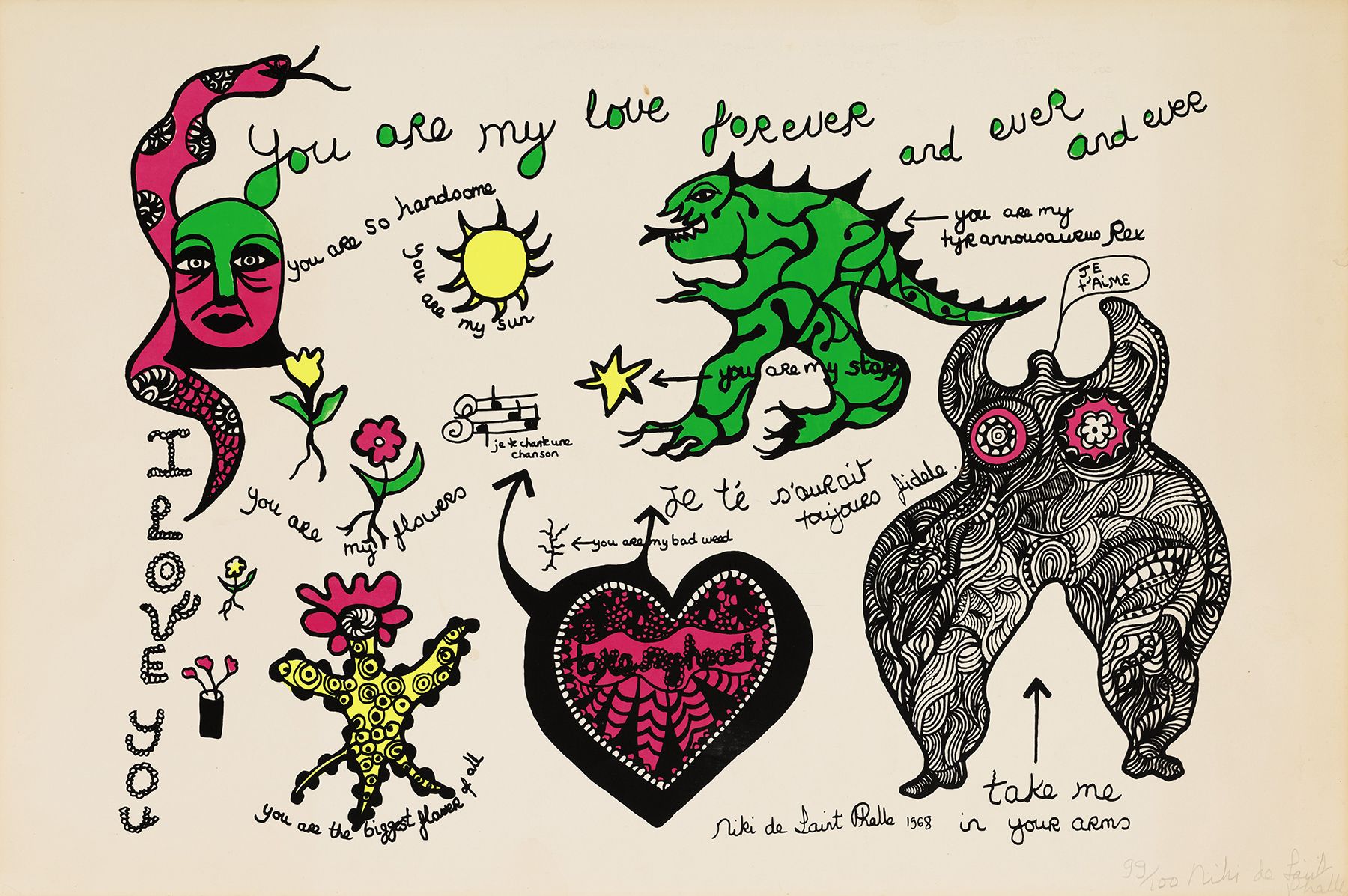

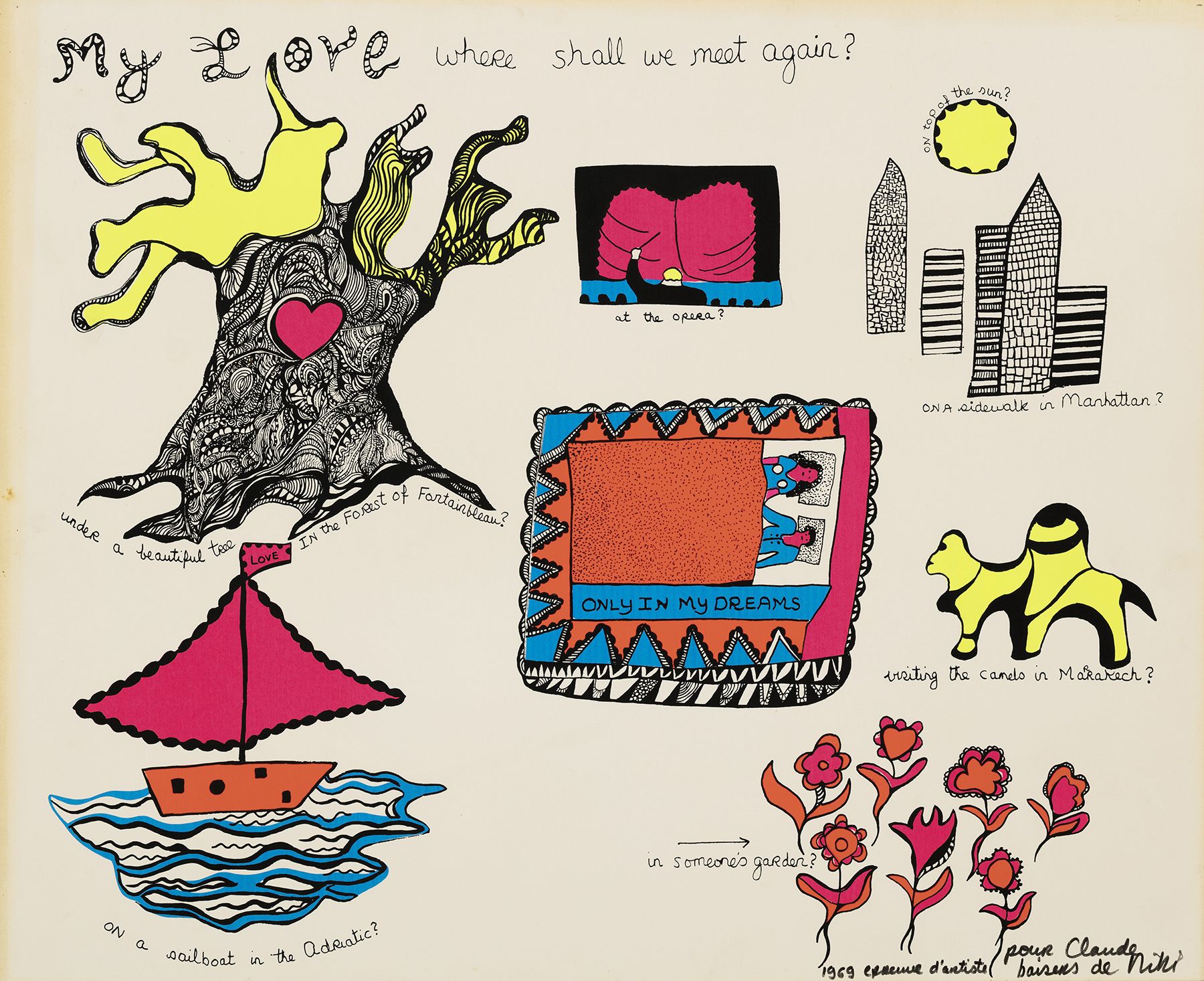

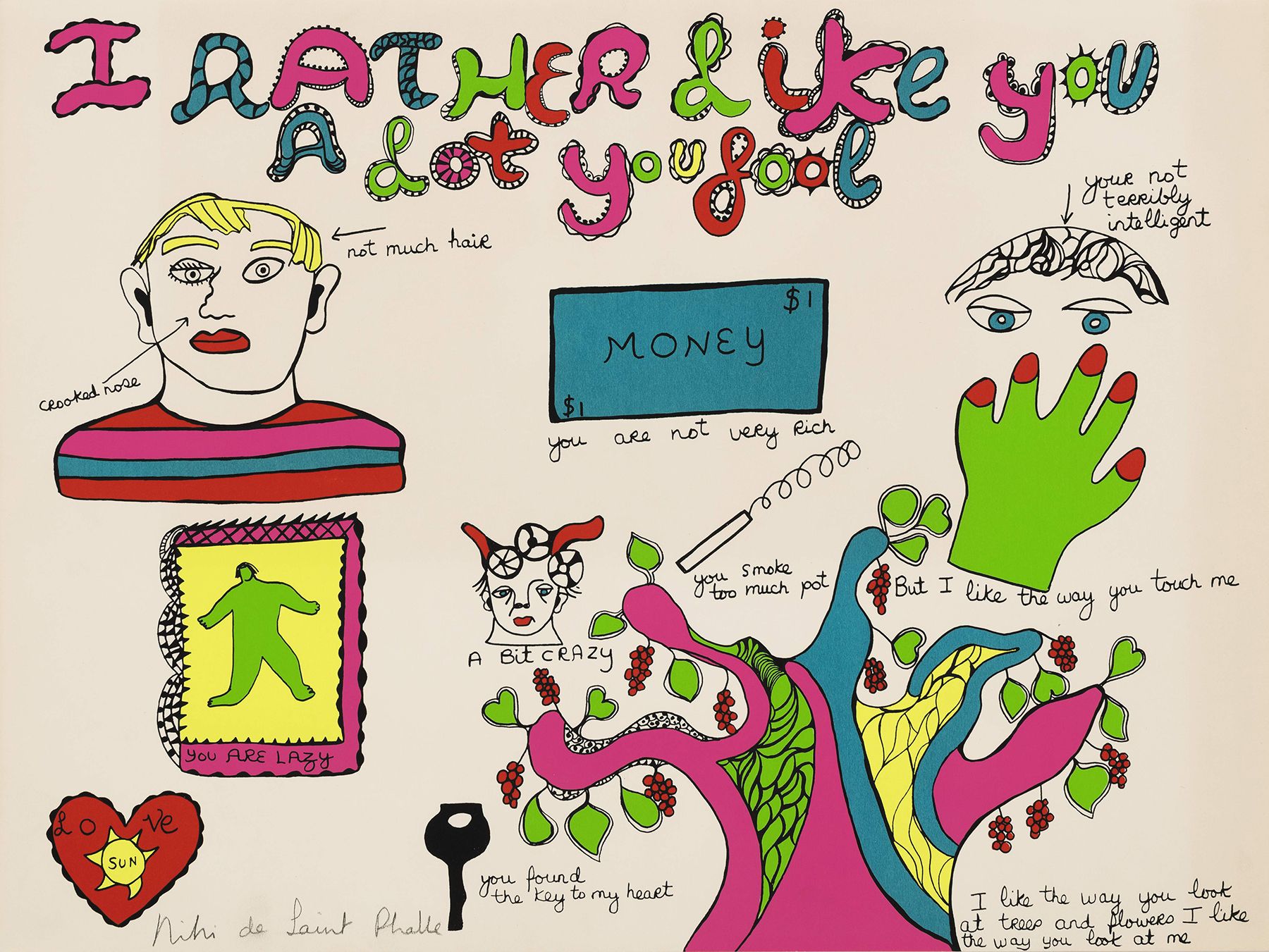

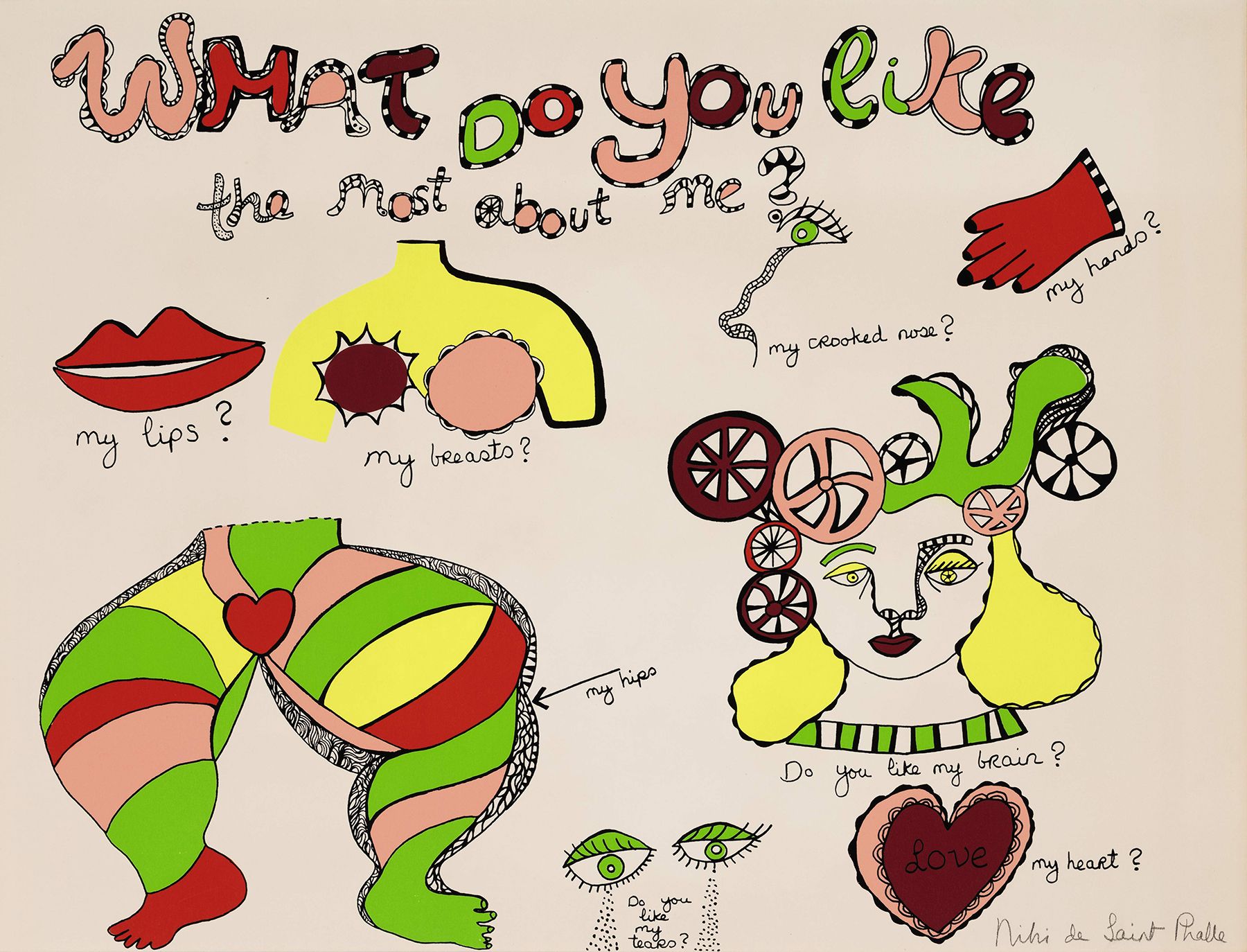

In addition to these built living environments, this blending of art and life was also evident in her lifelong practice of letter writing, drawing, and storytelling. Conflating drawing and writing, words and images, Saint Phalle created a vast opus of autobiographical works on paper. In her signature calligraphic script, she has told and revisited fragments of her turbulent personal history, and expressed her loves, aspirations, and political convictions in these drawings. Writing and drawing were more than just tools to explore her sculptural and pictorial ideas. They became one of the primary ways she could exorcise some of her most painful personal demons—transforming traumatic events such as her survival of incest and nervous breakdown, the breakup of romantic relationships, and the death of her loved ones into life-affirming stories that brought her peace and closure. Her portfolio Nana Power (1970) (once owned by François-Xavier and Claude Lalanne), installed in Gallery 3, is a prime example of this unique autobiographical aspect of her graphic practice. The Tarot Garden and her works on paper have, surprisingly, much in common: they each underscore the process of self-discovery. Deploying many of the recurrent figures that populate her work—Nanas, dragons, snakes, animals, esoteric symbols—Saint Phalle constructs vignettes of life, love, adventure and loss that conjure her own personal journey as well as that of the Nana as everywoman.

Niki de Saint Phalle made a decision to transform her anger and pain into a call to joy. She spent her life creating her safe space. Now on view.

This exhibition has been curated by Fabienne Stephan of Salon 94 alongside the Niki Charitable Art Foundation. Independent curator Alison M. Gingeras has written for and organized an extensive visual reader which will be available within the gallery.

For inquiries on the work of Niki de Saint Phalle, please contact fabienne@salon94.com

General inquiries may be addressed to info@salon94.com

For press inquiries, please contact Sophie Wise at sophie@companyagenda.com

[1] Nana Power.

[2] Niki de Saint Phalle in Niki de Saint Phalle: Here Everything is Possible (Ghent, BE: Snoeck Editions, 2018), 115.

[3] Niki de Saint Phalle in Catherine Francblin, Niki de Saint Phalle: La Révolte à l’œuvre(Paris: Hazan, 2013), 144.

[4] Roger Cohen, “AT HOME WITH: Niki de Saint Phalle; An Artist, Her Monsters, Her Two Worlds,” New York Times, October 7, 1993.

[5] Niki de Saint Phalle quoted in Camille Morineau, “Down with Salon Art! The Pioneering, Political, Feminist and Magical Public Work of Niki de Saint Phalle” in Niki de Saint Phalle 1930–2002, ed. Phillip Sutton (Bilbao: Guggenheim Bilbao, 2015), 362.

[6] Niki de Saint Phalle quoted in Claude Arthaud, Les palais du rêve (Grenoble: Arthaud et Paris-Match, 1970), 223.

[7] Niki de Saint Phalle cited by Renate Kremer,” At Least I found the Treasure”

[8] Benno Graziani, interview with Niki de Saint Phalle, Express Style Supplement no. 8, May/June 1987.

Press

Air Mail News

Interior Design