MICA

Installation Views

Artwork

MICA presents four decades of vessels and sculptures by ceramicist Christine Nofchissey McHorse (1948 - 2021), tracking the development of McHorse’s unique personal style and refined experimentation with the mineral-rich, micaceous clay of New Mexico. Initially exhibiting within her community and at Santa Fe’s renowned Indian Market, McHorse’s work came to represent a specific ingenuity across the wider field of contemporary ceramics, defying expectations and traditions and exploring form with a technical virtuosity. This exhibition is organized with the Estate of Christine Nofchissey McHorse, Garth Clark, and Mark Del Vecchio.

For additional information about this exhibition, please contact Andrew Blackley (andrew@salon94.com).

Christine Nofchissey McHorse: MICA

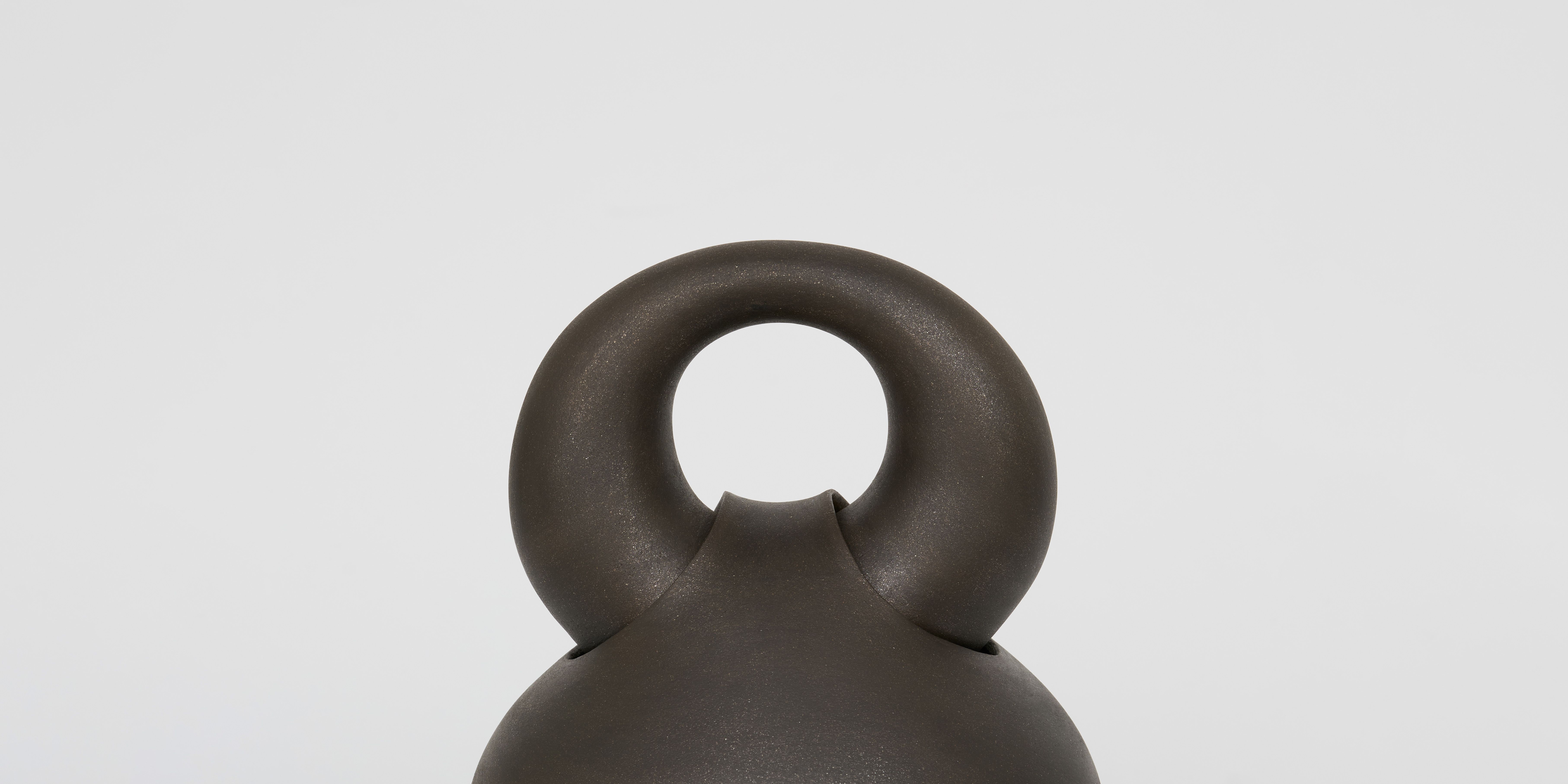

Wholly in black, a micaceous clay vessel absorbs and reflects slivers of light, revealing a smooth yet imperfect surface shaped by the symbiotic relationship of hands and clay, maker and material. The large, bulbous body of the vessel is almost fleshlike, reminiscent of a well-fed and tender belly. The vessel does not have a typical mouth, but a curling top that loops into and out of itself. Within the stretch of a singular, continuous clay structure, there are two openings where the curl enters and exits the vessel. Smooth at its entrance, the loop of the curl finds its end through a scratched exit. Perhaps erotic, the curl is ouroboros-like. Like a spirit line commonly etched onto many of the works of Christine Nofchissey McHorse (1948–2021), it finds a way out through itself. Cirque (2016) embodies McHorse’s dedication to form and a style that evolved over decades.

Christine Nofchissey McHorse: MICA explores the five-decade artistic career and legacy of the Diné/Navajo ceramicist, the first in her family. Born and raised in Morenci, a small mining town in southeastern Arizona, McHorse was Tódích’íi’nii (Bitter Water clan) born for Kin Yaa’áanii (Towering House clan), and spent summers herding sheep with her grandmother at her home near Fluted Rock at Cross Canyon, Arizona, on the Navajo Nation. While she eventually lived and worked in New Mexico for most of her life, she was a cosmopolitan in her own right. Perhaps embracing the nomadic histories of the Navajo, McHorse traveled and learned from many people in different communities in the US and abroad. Grounded in Native methods and materials, working on the continuum of Navajo innovation and with a range of techniques, McHorse drew inspiration from the whole world, pushing the limits of clay’s form and structure to create striking vessels, visually distinct from any specific lineage.

In 1963, she began attending the Institute of American Indian Art (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico, for high school and post-graduate studies. There, she met her husband, Joel, a Tiwa silversmith. She learned jewelry making, metalwork, design, painting, and drawing, but returned to clay and ceramics, experimenting with shape, texture, technique, and symbol. After McHorse left IAIA and married Joel in 1969, Lena Archuleta, Joel’s grandmother and a potter who owned a curio shop, recognized and cultivated McHorse’s talent. She taught McHorse where and how to gather sparkling micaceous clay found near Taos Pueblo. She made coiled pots in traditional shapes, honoring her Diné roots by utilizing piñon pitch, a Navajo method of waterproofing and glazing that uses piñon sap as a lacquer and sealant.

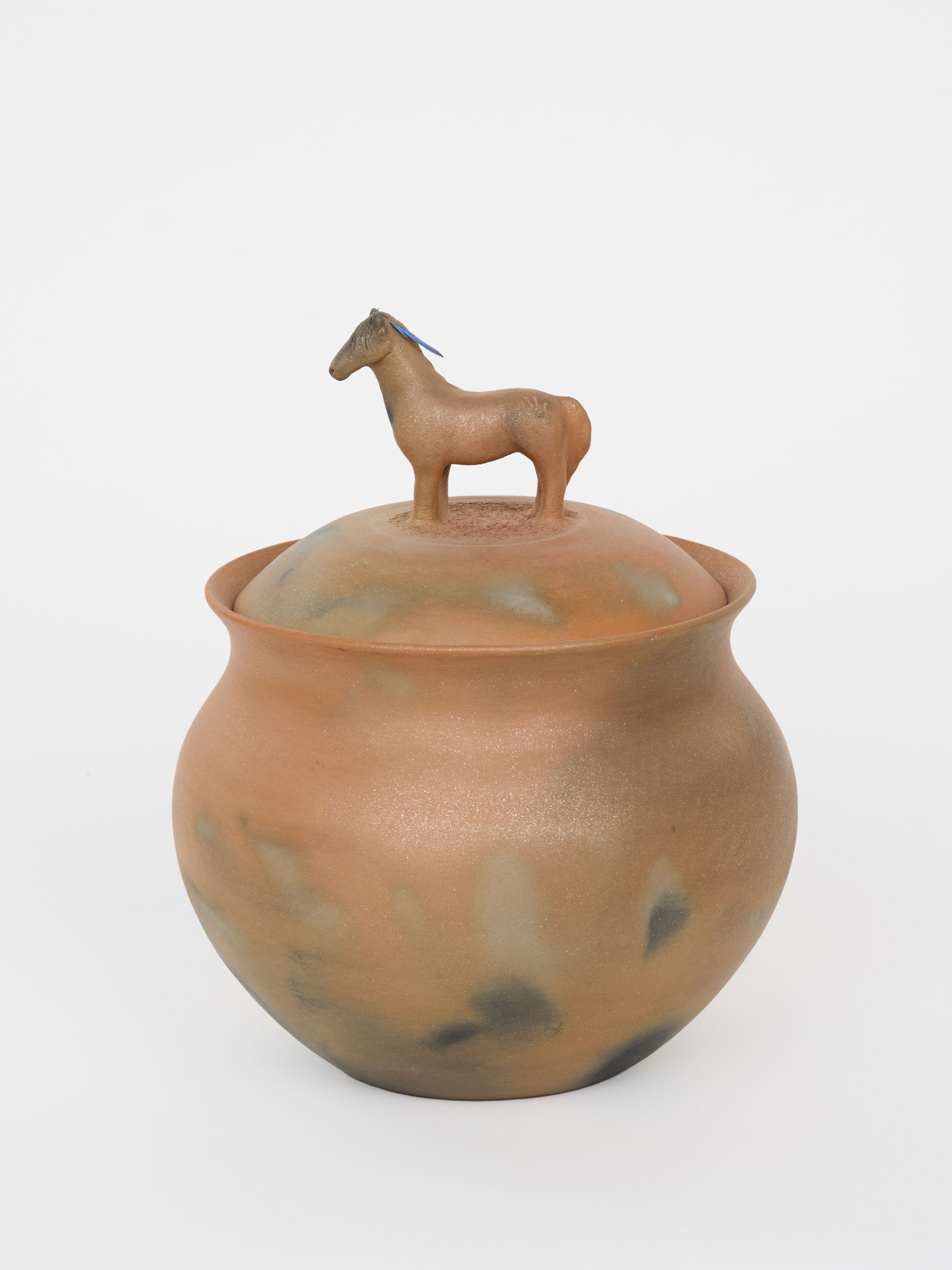

By 1971, McHorse began exhibiting at state fairs and Native art markets like the Santa Fe Indian Market and selling work at Archuleta’s shop. Small and decorative, this work differed drastically from Cirque. As McHorse’s style evolved throughout the 1980s: she collaborated with painter Joseph Calabaza on Avanyu Charger (1988) or used a decorative scratching technique called sgrafitto in works like Navajo Piñon Pitch Vessel with Sgrafitto Decoration (1989). By the 1990s and into the 2000s, her fascination with form became apparent as she incorporated three-dimensional figural decoration in works like Horned Toad Lidded Vessel (1990) and Kiva Step Lidded Pot (1992). These works earned McHorse many ribbons and awards at Native art markets and the Museum of Northern Arizona’s Navajo Festival.

After gaining a comfortable level of financial and artistic success, yearning to create work less restricted by specific buyer demands and make space for up-and-coming artists, McHorse began to pull away from the Native art market scene in the early 2000s. As her work changed, McHorse’s talents were noticed by New York City galleries and collectors like Garth Clark and Mark Del Vecchio, who were primarily interested in her work’s formal and contemporary qualities. This shift in audience and buyers, as well as inspiration from trips to Europe, allowed and encouraged McHorse to experiment with scale and shape throughout the 2000s. Developing a distinct style in the same coiled clay that she gathered near Taos Pueblo, she embraced larger, darker micaceous clay works, leaving behind almost all decoration throughout the 2010s.

McHorse experimented not only with scale, but negative space and clay’s resistance to gravity to create delicate swirls like in Stira (2005), and porous, cascading structures like Vesuvius (2002). While the influence of nature became less explicit in decoration, structural elements of her work began to look like the earth. Vesuvius, for example, is akin to the wind-carved sandstone landscapes seen across northern Arizona. Constantly curious, McHorse experimented with firing and form until she died in 2021.

Like an architect and sculptor, McHorse would often work out a vessel’s technical complexities on paper before translating it to clay. While maintaining her distinct style, McHorse took inspiration from other artists and media. Works like Spider Trap (2006) or Germination (2009) are reminiscent of Constantin Brancusi, Henry Moore, or even the curvaceous bronze sculptures of feminine figures by Allan Houser, her former IAIA instructor. McHorse would often respond “maybe” when viewers would make guesses about what her structural vessels might mean. While their titles sometimes gave hints, she was often mysterious about the meanings of seemingly sexual works like Calla (2016) and Spleen (2016).

McHorse once stated, “I like making vessels because it’s a practical thing for me…but I also like vessels that most people wouldn’t know what to put in them. I guess in a way I’ve already filled [them] with my time and my energy.” Like a vessel herself, McHorse contained a multitude of identities and vast amounts of knowledge, always experimenting in clay because it “allowed her to do what she wanted,” according to Del Vecchio. The largest exhibition of her work to date, Christine Nofchissey McHorse: MICA illustrates the evolution of McHorse’s clay artistry over time and the importance of artistic freedom unbound by expectation and rigid tradition. Beloved and encouraged by her family, peers, and collectors, and motivated by a desire to forge her own style and lineage of pottery while maintaining reverence for her teachers, McHorse established herself as an artist and potter who blurred, blended, and advanced the lines between form and function, pottery and sculpture, tradition and innovation.

Text by Isabella Robbins