Huma BhabhaFacing Giants

Walking through the exhibition is like stepping into the diorama of a fantastically reimagined archeological site, with excavated features, artifacts, and relics waiting to be surveyed. — Danielle Shang, 2021

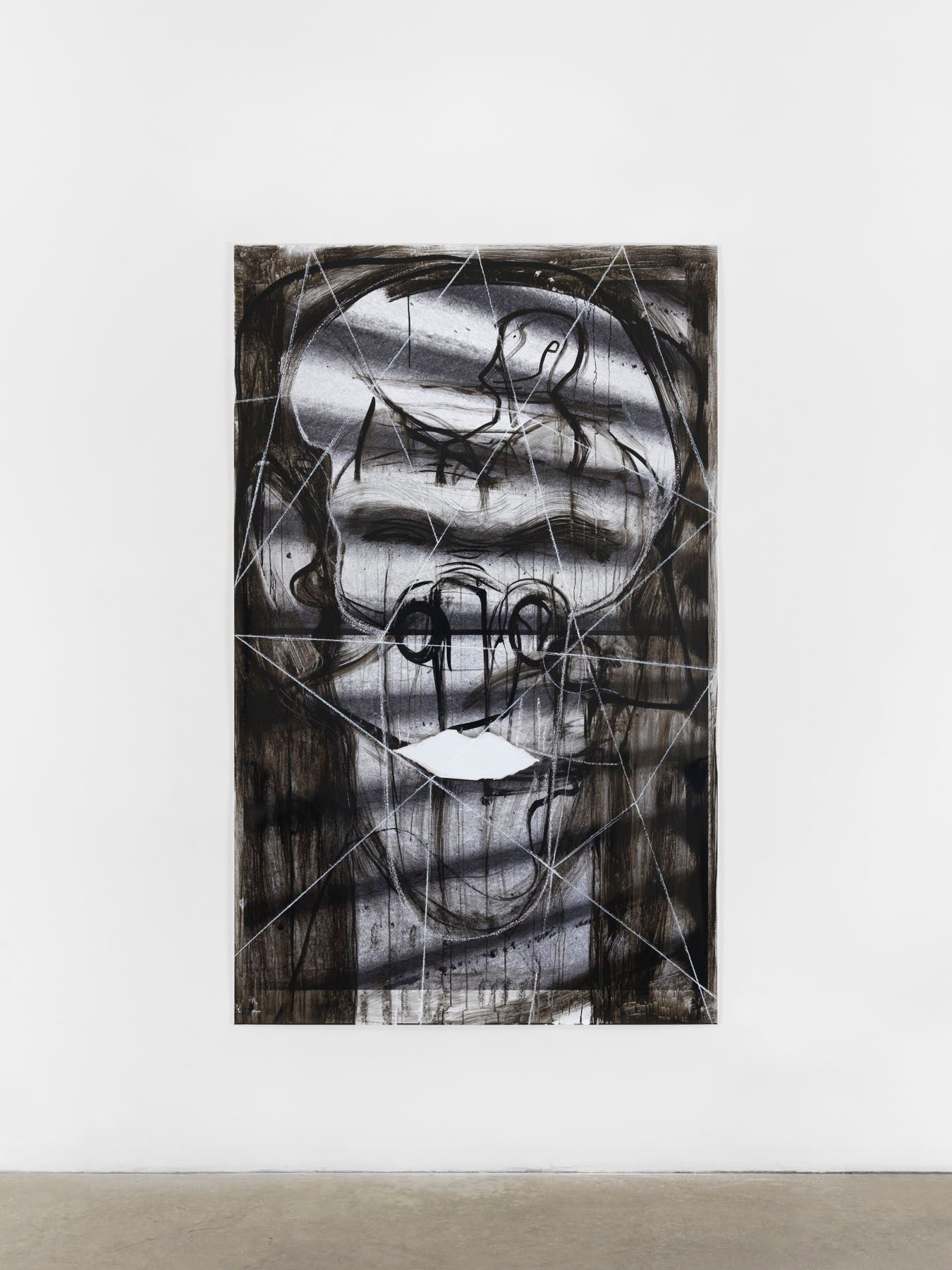

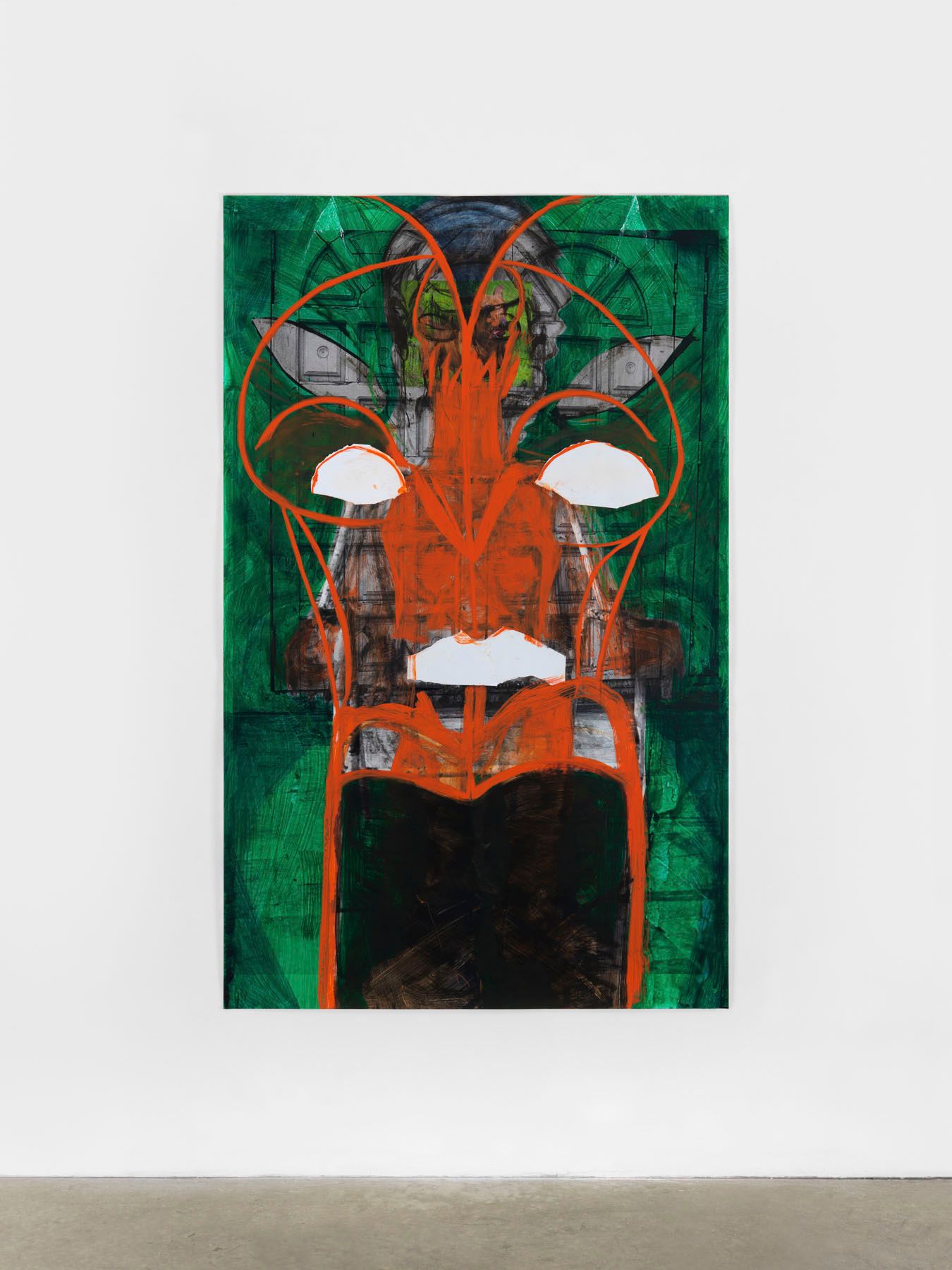

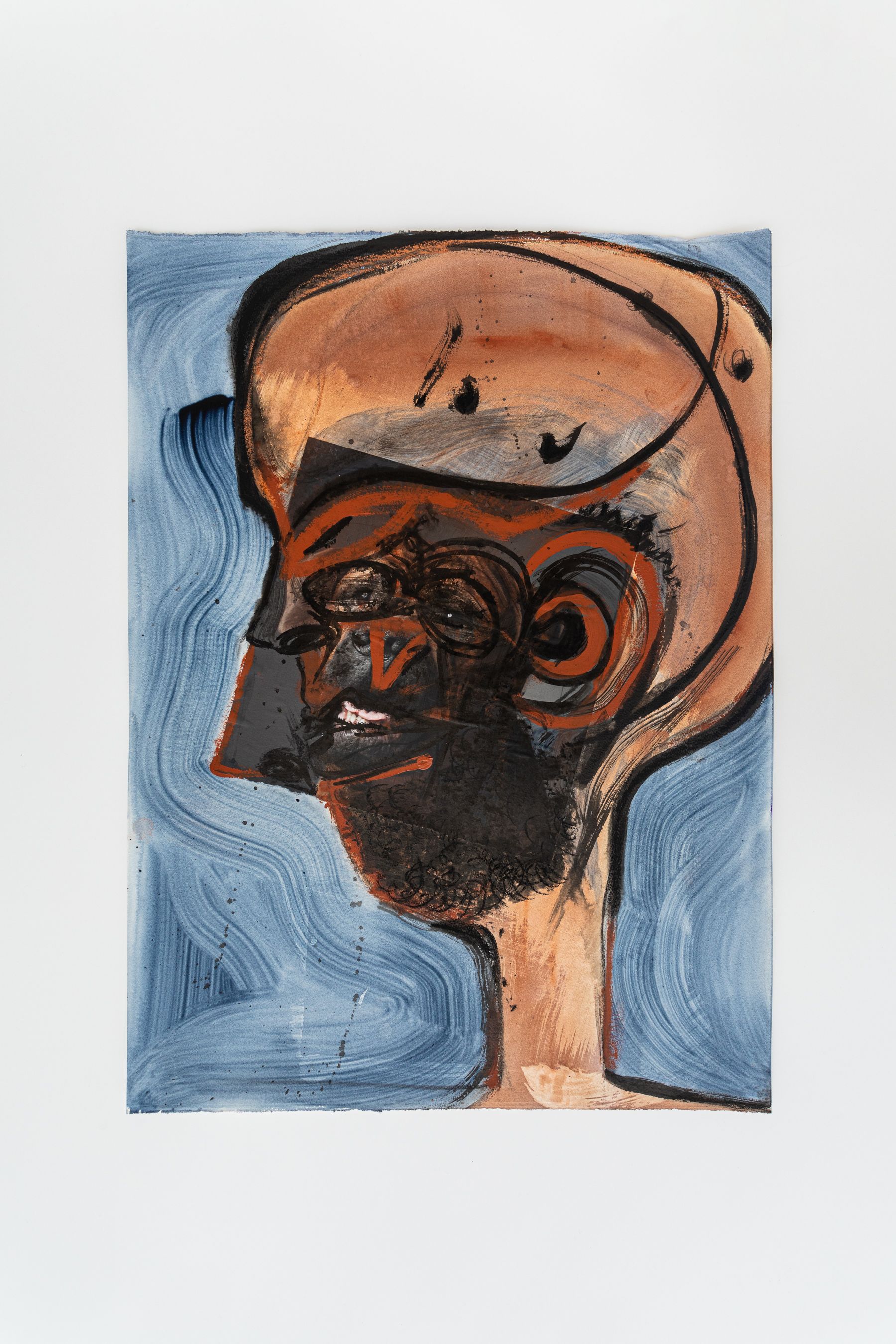

Installation Views

Artwork

Huma Bhabha: Facing Giants

By Danielle Shang

For the past three decades, Huma Bhabha’s approach to sculpture, printmaking, and drawing has been informed by archaeological interpretation, which enables her, through the implement of stylistic association, to reimagine temporality and spatiality in accordance with both data excavated from the distant past and her own state of mind and vision for the future. Her sculpted characters—anxious, votive, mysterious, and sublime—attest her personal exploration of iconographic languages and formal vocabularies of the archetypes of ancient mythology and monuments.

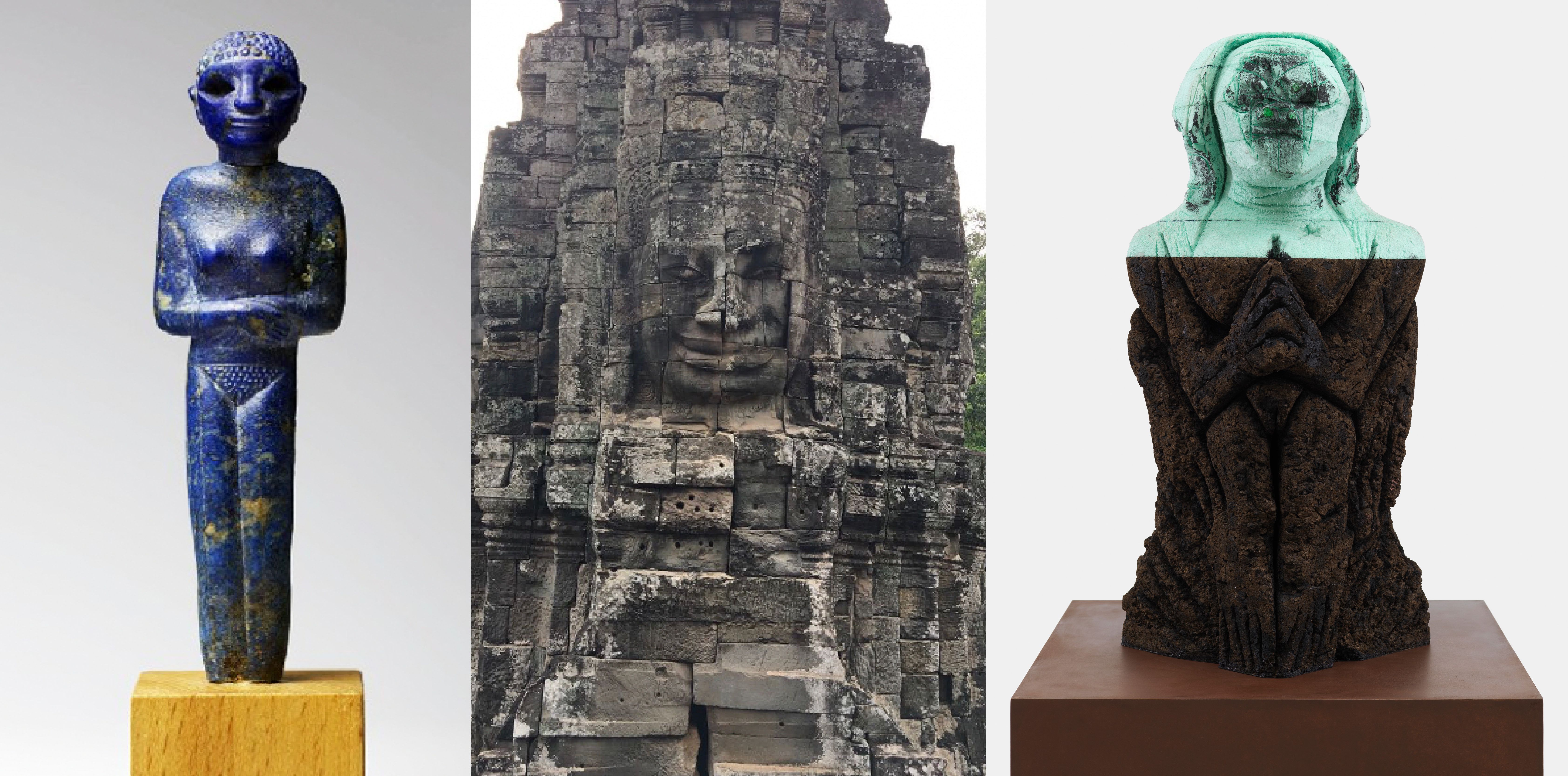

Left: Statuette of a female idol (ca. 3300–3000 BCE, Hierakonpolis, Egypt). Image: Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford.

Center: Facetowers at Bayon Temple in Angkor Thom (12th century AD, Siem Reap, Cambodia). Photo by the author.

Right: Huma Bhabha, Amy (2021). Cork, Styrofoam, acrylic, oil stick.

Take Amy (2021) as an example: a compact female figure with a defaced Sphinx head chiseled from a thick column of stacked dark cork on the bottom and light green Styrofoam blocks on the top, standing upright on a pedestal at a modest height of 31 inches. The symmetrical statue seems to be molting behind its slough that cracks open on the back and emerges forward. The body is entirely unclothed; the feet are close together; one pair of arms bends forward at the elbows with the hands clasped across the chest in a gesture of offering prayers; the other arms are perfectly morphed into the sides of the body. The pose alludes to that of votive female idols from Egypt’s Predynastic and Archaic periods, exemplified by the exquisitely carved small lapis lazuli idol in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology at the University of Oxford. Bhabha animates Amy by loosely incising and painting on the sculpture’s coarse surfaces to delineate streamlined anatomical features. The head, adorned with an Egyptian royal nemes headdress, appears either decomposed or vandalized and riddled with scars, evoking violent narratives and the passage of time. The ancient Egyptians ascribed important powers to the image of the human form, in which a deceased ruler’s soul inhabited and attained deity. However, a great number of monumental statues later became subject to iconoclastic campaigns of facial disfigurement, which damaged representations of the almighty for the purpose of deactivating their images’ supernatural powers. Ironically, thousands of years later, the disgraced idols are sanctified once again, worshipped in museums—the temples of culture.

It is also worth noting that Bhabha treats the solid form of Amy with an architectural sensibility for structural arrangement, calling to mind ancient stone monuments such as the Bayon Temple in Angkor Thom (12th century AD, Siem Reap, Cambodia). This awe-inspiring ruin of anthropoid towers was built entirely from dark sandstone blocks with enormous faces carved on the exteriors to portray the Jayavarman VII—the powerful Khmer king—as the divine god bodhisattva, who postponed entering Nirvana, the eternal existence of the soul, in order to remain on earth helping others towards salvation.

Also simultaneously sculptural and architectural is Bhabha’s elongated pillar-like Prime Traveler (2021), an 88-inch-tall bronze female figure with Princess Leia–style hair buns and an exaggerated visage engraving atop, reminiscent of the Hathor columns in the massive Dendera Temple (built beginning ca. 1995 BCE, Qena, Egypt), whose capitals are elaborately carved to depict the cosmic goddess Hathor’s head. This concept of anthropomorphic support was later developed into shafts with Osiris statues attached in the front at the mortuary temples of Ramses II (1279–1213 BCE) in Egypt, and further transformed into the celebrated caryatids, sculpted female figures serving as tectonic supports of entablatures on their heads, at the Erechtheum (built between 421 and 406 BCE) on the Acropolis of Athens. Another example of half-architectural and half-sculptural form in Bhabha’s repertoire of sculptural typologies is I Know (2021), a seven-foot-tall narrow rectangular wood slab with a mysterious body—in a similar votive pose to that of Amy—carved out of a flat panel of dark cork in medium relief attached to the front. The stela stands directly on the floor leaning against the wall in a niche in the Stone Room on Salon 94’s second floor. A bright pink rubber mold, discarded from the artist’s foundry, is placed on the top to suggest a head. The placement of the stela vividly evokes the statue of the sun god Re-Horakhty in the niche above the entrance of the Great Temple of Abu Simbel temples built by Ramesses II in ancient Nubia. The niche constitutes a doorframe of the passage for the sun god to journey to another world, carrying prayers and blessings of the living with the souls of the dead. Confronting the anthropoid stela vis-à-vis is the eight-foot-tall bronze figure Receiver (2019), a phantasmal giant, characterized by the frontal and symmetrical rendering with the left foot slightly forward and the mouth curved upwards to form the Archaic smile. It receives the divine messages from the sun god with the gesture of attentiveness: two hands clasped at the chest. An additional pair of arms is tightly connected to the sides of the body.

Prime Traveler and I Know, like much of Bhabha's work, can be read as the artist’s homage to anonymous masters in history; on the other hand, the formal association is also the device for her to articulate the notions of sanctity and monumentality—“the spiritual quality inherent in a structure [large or small] which conveys the feeling of its eternity.” [1]

Left: Huma Bhabha, Rosebud, 2021. Bronze, 41 x 15 x 15 inches.

A few other bronze statues in the exhibition are modeled from clay, found objects, and raw materials—such as the enigmatic Rosebud (2021), a 41-inch-tall bronze shaped like a flower bud erected on a pair of bare feet. A small phallus is attached to the pedicel. The title is derived from the dying man’s last word in the iconic film Citizen Kane (1941) by Orson Welles. This swan song is often interpreted as the marker of the moment at the very end of life when one experiences an illusory flashback to the lost innocence of childhood. British film critic Peter Bradshaw remarked, “We all have around two or three radioactive Rosebud fragments of childhood memory in our minds, which will return on our deathbeds to mock the insubstantial dream of our lives.” [2] The surface of Rosebud is agitated, knobby, and blotched, betraying the spontaneous modeling process, similar to that of Picasso’s Man with a Lamb (1943), in which the clay was patched, pulled, pushed, sliced, pinched off, and stuck back on. Bhabha is clearly interested in the rawness and immediacy of the material manifestations through her probing working method: exploring and contemplating, adding and subtracting, making and unmaking. Although there are layers of patina, her fingerprints are vividly pronounced on the surface, and the narrow fissures created by knifing through the wet clay to depict toes are visceral. The materials in play give a nod to her early forays, beginning in 2001, into the human form. Works such as International Monument (2003) and Man of No Importance (2006) are constructed from clay, Styrofoam, chicken wire, and a variety of found objects—materials perceived by others as mundane, underlining Bhabha’s deep respect for their past lives and her deep desire to renew their existence.

Among the found objects incorporated in Bhabha’s sculptures are animal skulls and bone fragments. In Pathfinder (2021), a miniature statue carved from cork and elevated on a pedestal, the frontal body is expressively incised, giving the sculpture painterly lineate details. The back of the body is chiseled in sunken relief—a technique largely restricted in ancient Egypt—creating the illusion of depth and spatial recession by forging strong tonal contrast to bring to the foreground, the trapezius, buttocks, and limbs on the flat surface in contrast with the dark sunken shadows that form the contours. The torso is crowned with the exoskeleton of a horseshoe crab, adding the weight of mortality and denoting the passing of time. By juxtaposing factory-produced material with ephemera found on the seashore, the artist puts the ravages of time between nature and culture on display—reminiscent of the Surrealist practice of transforming found objects through unexpected juxtapositions. For Bhabha, assemblage is, as it was for Eileen Agar, “a form of inspired correction, a displacement of the banal by the fertile intervention of chance or coincidence.” [3] Moreover, through this process, Bhabha refutes monuments that romanticize power, grandiosity, nostalgia and, most importantly, immortality, while erasing the memory of violence, resistance, and oppression. Memory is a labile thing. As time passes, conditions shift, narratives are altered, and memory is caught in limbo and fraught with dubiety. If memory is such a fleeting construct, then monuments of the powerful and canonical—haunting ghosts from the past—almost always risk falling into disgrace shortly after, evident in today’s rise of fallism. In contrast, the relic of a humble displaced bottom-dwelling scavenger will continue to exist in a renewed life, holding its past and carrying it into the future.

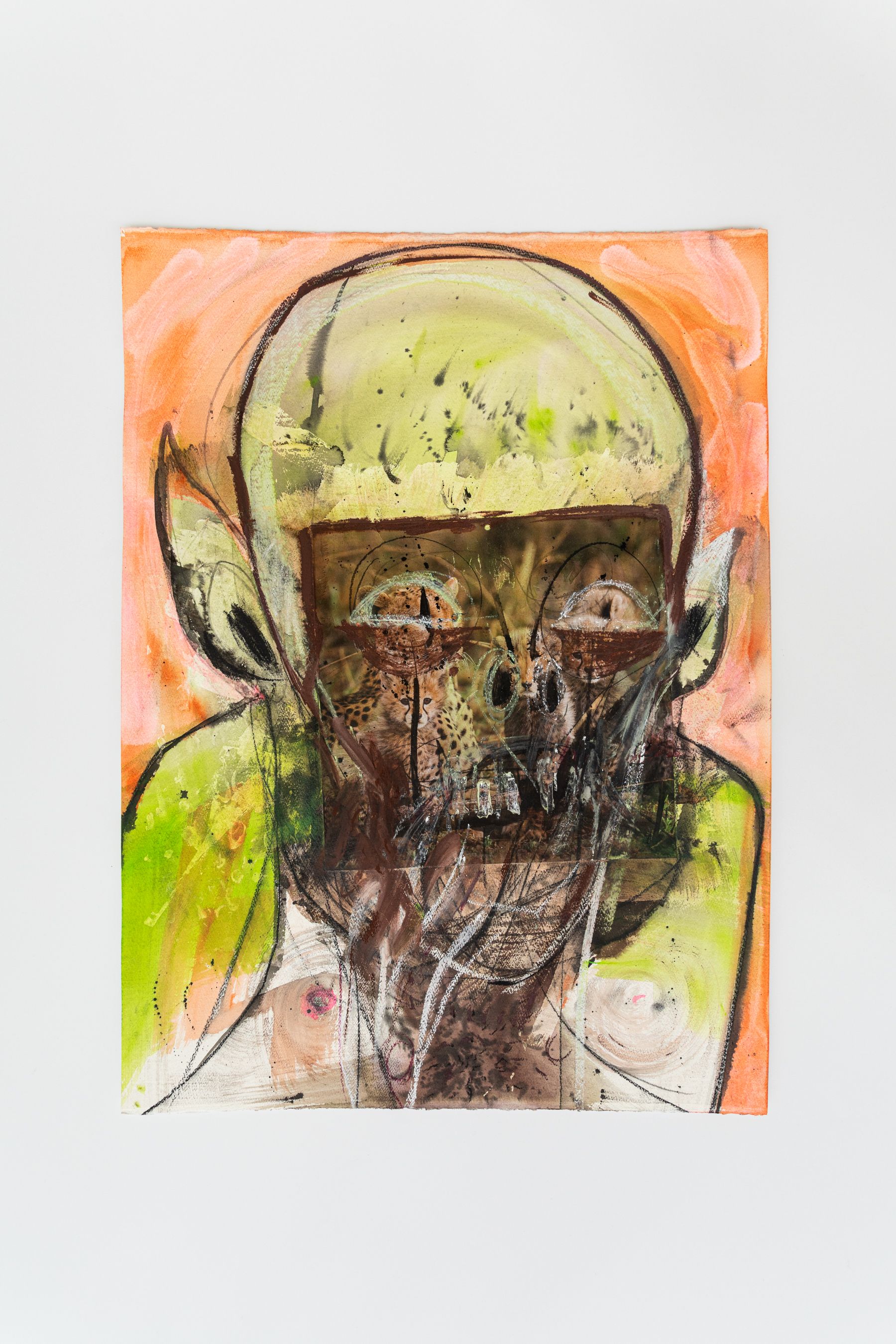

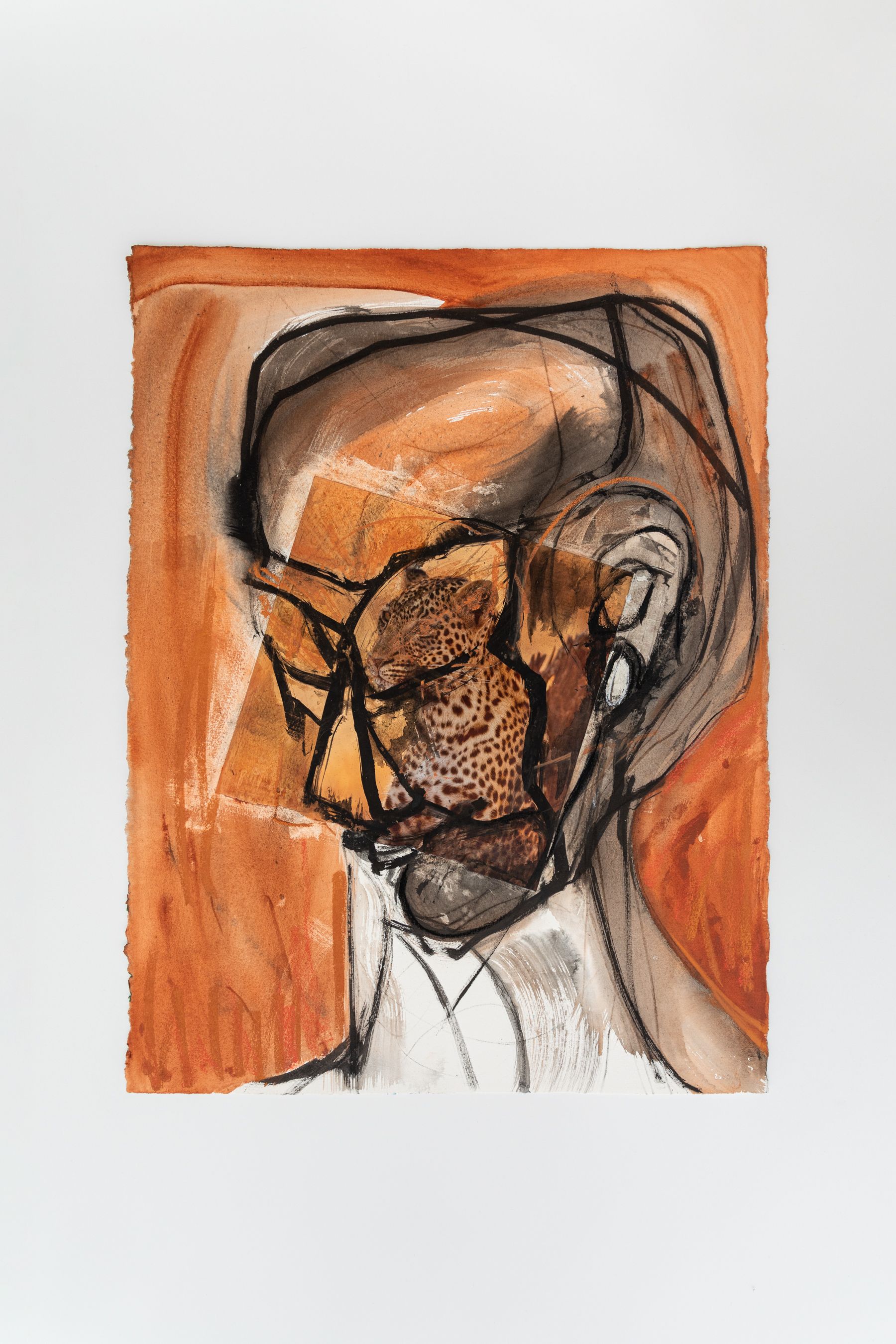

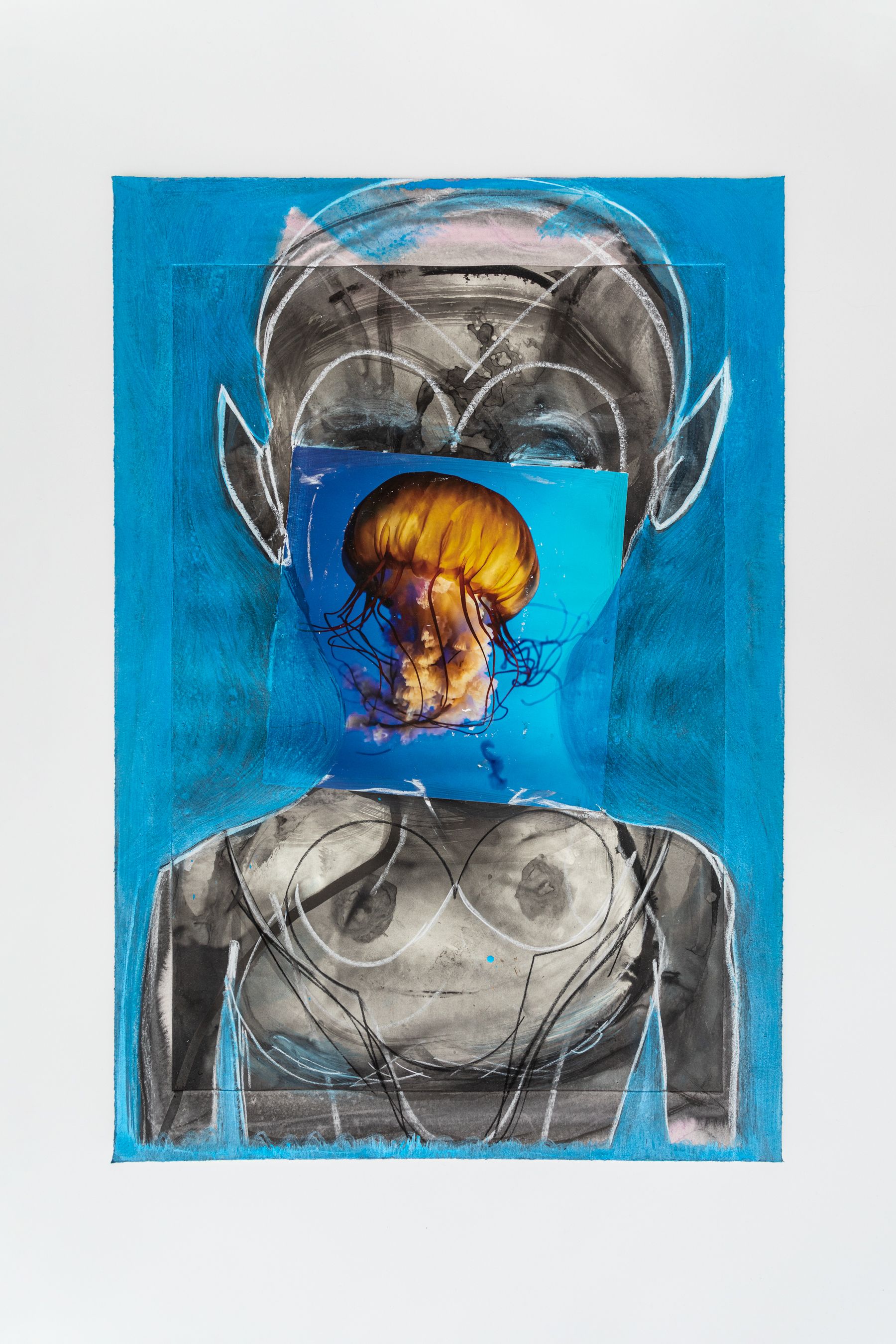

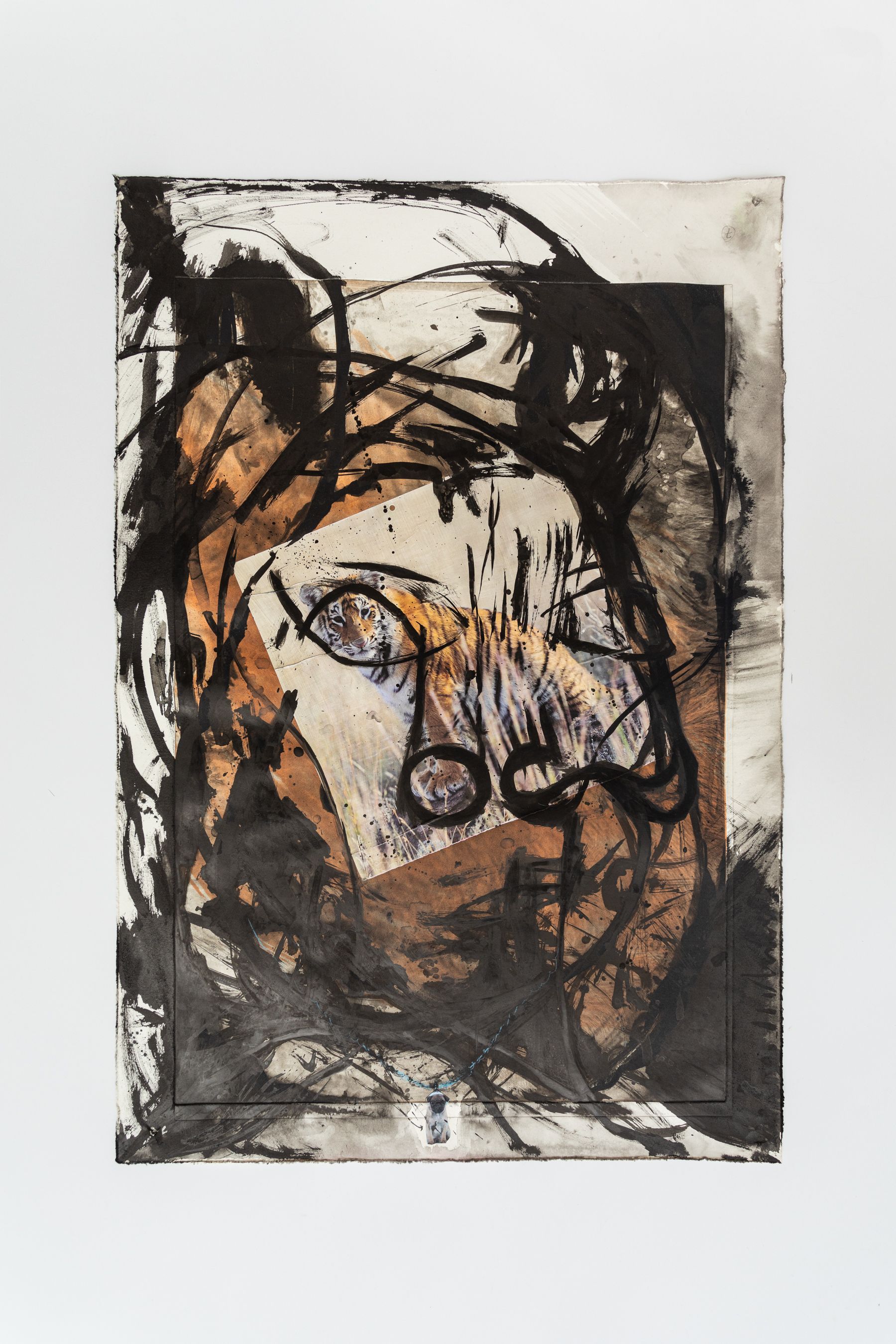

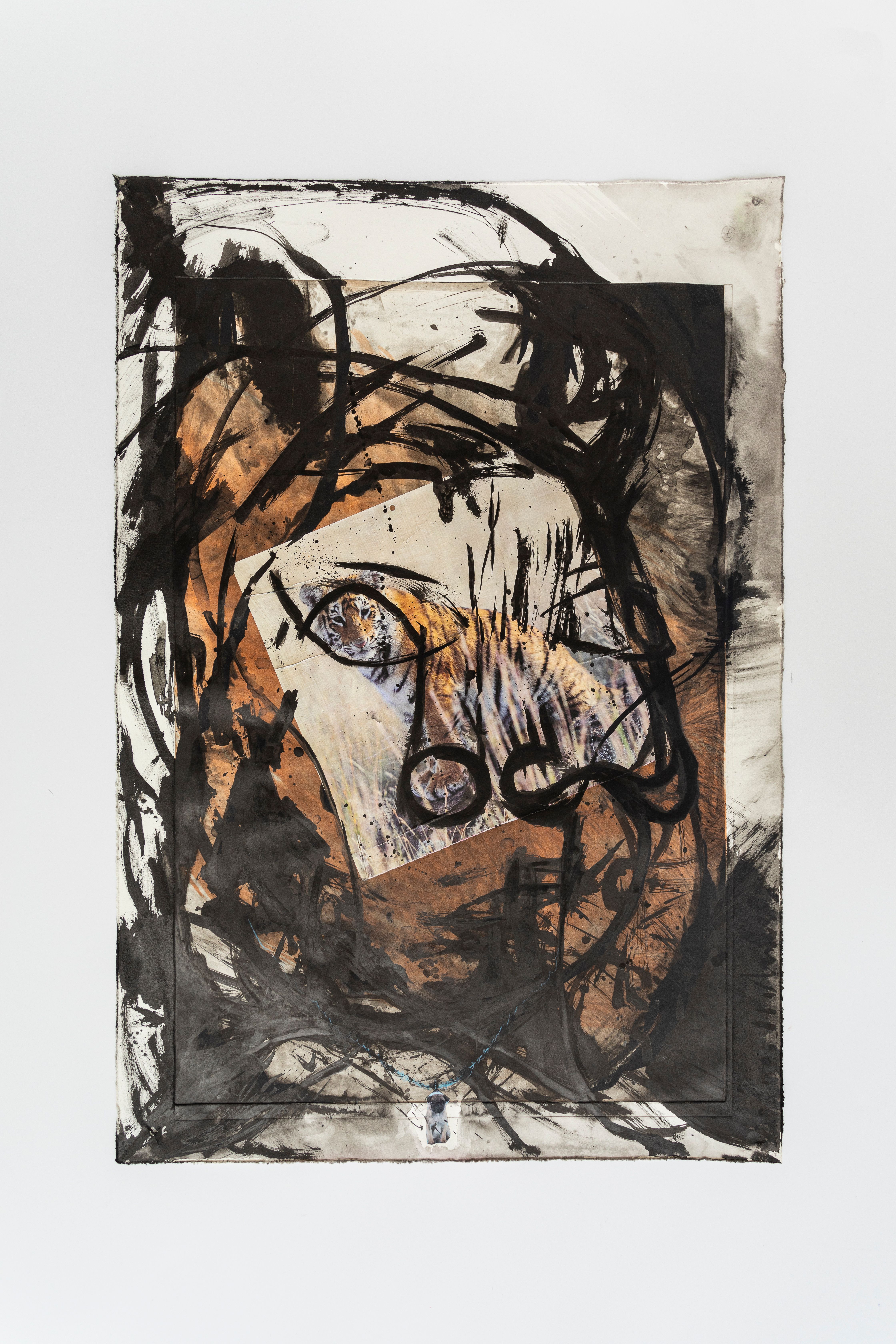

Huma Bhabha, Untitled, 2020. Ink, acrylic, pastel, and collage on paper, 34 3/4 x 23 1/2 inches.

Anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss suggests that animals have historically empowered us with metaphors to discuss how we are born, live, and die—and perhaps what happens to us afterwards. An environmentally conscious person and animal lover, Bhabha often integrates small clippings of wildlife and domesticated dogs from old calendars into her allegorical over-painting—a practice of delineating deconstructed anatomical portraits on substrata of photographs and prints. For the artist, animals are agents of sacred power. In one new work on paper, a young tiger occupies the pictorial center, gazing tenderly at the viewer through the hollow socket of the right eye of a loosely depicted skull. The vigorous ink strokes that form the skull call to mind action painting or Chinese wild cursive calligraphy in its unconstrained lines, wet texture, and indexing of the artist’s movement. The blot, right stroke, down stroke, broad edge, hook, lift, press down, turn, center tip, side tip and so on—to borrow from terms of Chinese calligraphy—work together in a flowing manner to trace the artist’s unbroken energy, making evident her response to the aesthetic potential of brush and ink. Brush and ink, though instruments of gesture rather than sound, can nevertheless demonstrate the harmony of music imbued with spiritual resonance. Similar to Anselm Kiefer’s arresting painted-over photographs, Bhabha’s work on paper compels the viewer to undertake a critical investigation of the pictorial surface to reconstitute the mnemonic value in the photograph. The realistic picture of an adolescent tiger in the background and the deconstructed skull in the foreground rely on each other for existence: their sharp contrast heightens the senses of vulnerability, displacement, refugeedom, and annihilation. Like Joseph Beuys’s coyote, Bhabha’s tiger calls the viewer’s attention to the reciprocity of humans with the natural world at large. The tiger gazes at us from the painting with an inverted magnetism, pursuing our eyes, reminding us of the fragility of the material world, pleading us to reconnect with our spirituality and to heal environmental traumas before it is too late.

Bhabha’s work is incomplete without the viewer’s actions of looking and exploring. Only after attentive inspection of her open-ended oeuvre can one fully comprehend the performative force of giving shapes to the figures and discover the artist’s preoccupations with histories of the forgotten and narratives of survival. Walking through the exhibition is like stepping into the diorama of a fantastically reimagined archeological site, with excavated features, artifacts, and relics waiting to be surveyed. The exhibition’s range of materials, visual forms, and media enables the viewer to time-travel and navigate history as it has been constructed by both the powerful and the powerless. Facing Giants’ mise-en-scéne relies on the viewer’s critical reading to scrutinize the aestheticization of the past and interrogate the relationship between memory and representation, the promise of transcendence, and nature of mortality. Robert Hughes's description of Cézanne's attitude toward painting could equally be applied to Bhabha’s practice: “A vast curiosity about the relativeness of seeing, coupled with an equally vast doubt that he or anybody else could approximate it in paint.” [4]

In light of the iconoclasm of our current age, as people around the world reject the established cultural patrimonies by destroying public memorials, it is perhaps more accurate to consider Bhabha’s phantasmal monuments as counter-monuments, as what James E. Young, a renowned scholar in memory studies, described: “a process of remembrance that occurs in the space between the memorial and the viewer, between the viewer and his or her own memory… in the viewer’s mind, heart, and conscience.” [5] In Huma Bhabha’s work, the eternal and the ephemeral coexist, and dystopia and dreamland collapse into one to bridge to the bygone eras, in which the myth of mankind’s destiny is born.

[1] Louis I. Kahn, Louis Kahn: Essential Texts, ed. Robert Twombly (New York: W. W. Norton, 2003), 21.

[2] Peter Bradshaw, “Citizen Kane and the meaning of Rosebud,” The Guardian, April 25, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/apr/25/citizen-kane-rosebud.

[3] Eileen Agar, A Look at My Life (London: Methuen, 1988), 148.

[4] Robert Hughes, The Spectacle of Skill: Selected Writings of Robert Hughes (London and New York: Vintage Books, 2016), 15.

[5] James E. Young, At Memory’s Edge: After-Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002), 118–119.

For information about the exhibition, please contact alissa@salon94.com.

For press inquiries, please contact Sophie Wise at sophie@companyagenda.com

Press

The Brooklyn Rail