Matthew KrishanuFalling Into Place

Installation Views

Artwork

Falling Into Place

Text by Tausif Noor

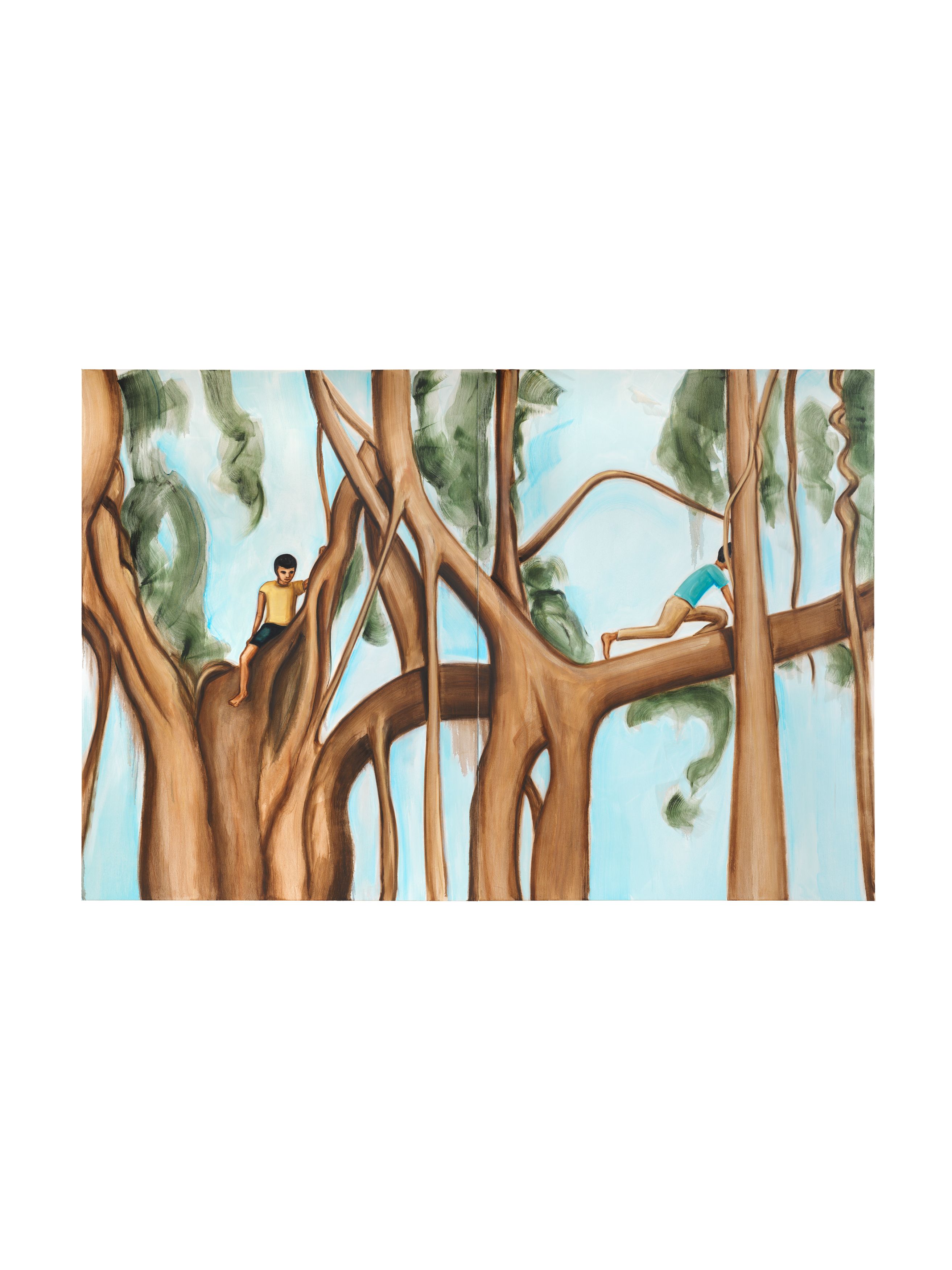

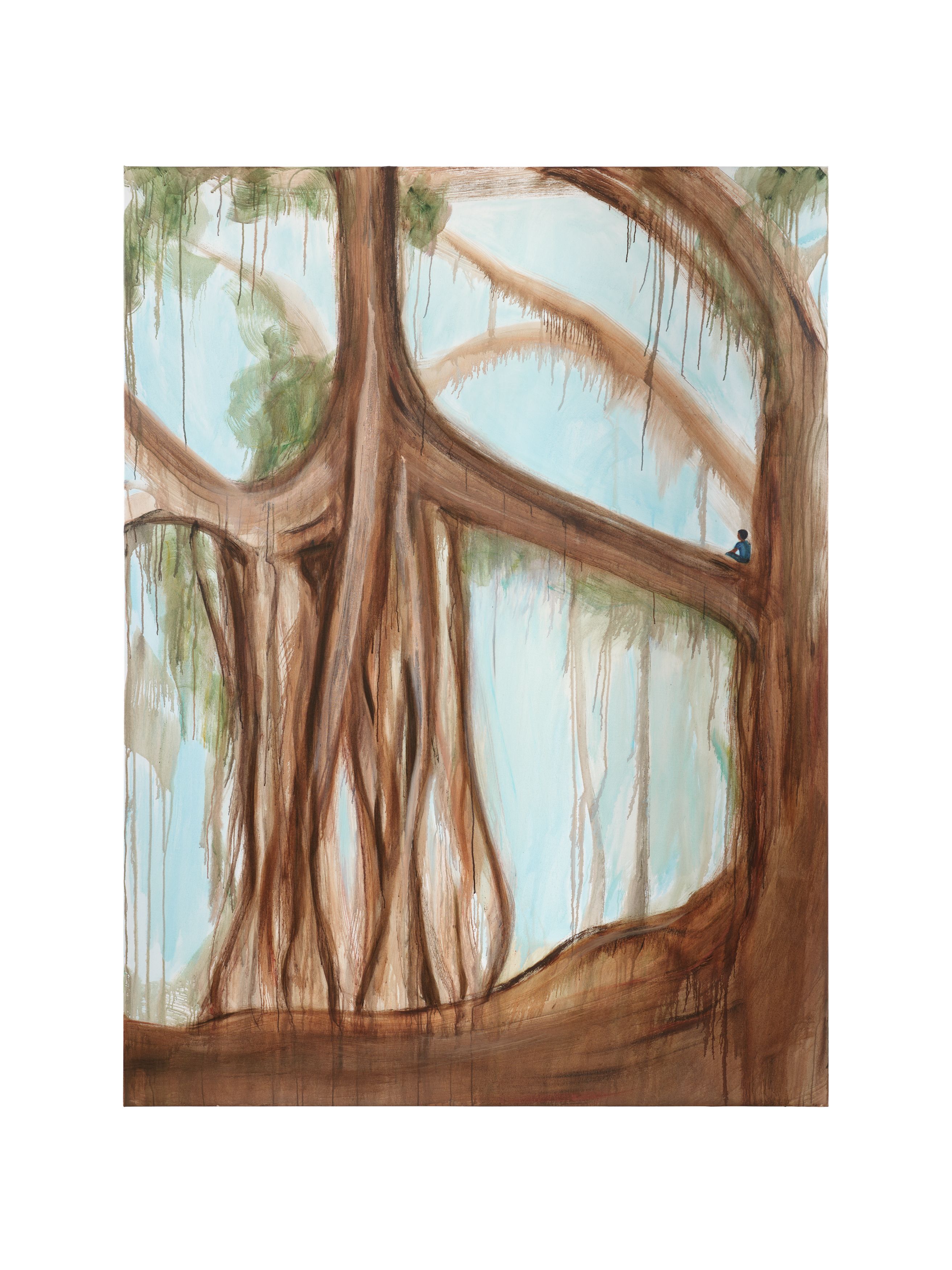

Matthew Krishanu’s depictions of childhood attest to how painterly freedom can be captured in both subject matter and form. The artist’s recent paintings feature the banyan tree, revered across cultures, and especially in South Asia, as a locus of spiritual significance and enlightenment. Beneath drooping leaves, the massive trunk sends out aerial and adventitious roots that can spread indefinitely. Rendering this ancient and mystical vegetation in large-scale paintings such as Banyan, Two Boys; Banyan (Boy, Blue); and Banyan (Woman, Red Sari), all from 2025, Krishanu remains faithful to its ethereal beauty and gargantuan size, scaling the human figures far smaller than the mahogany trunks and branches. Using acrylic and oil paint, Krishanu varies the weight of his brushstrokes, forming thick, dark outlines that frame and anchor the tree, lending it tangible weight and presence against a pale blue sky.

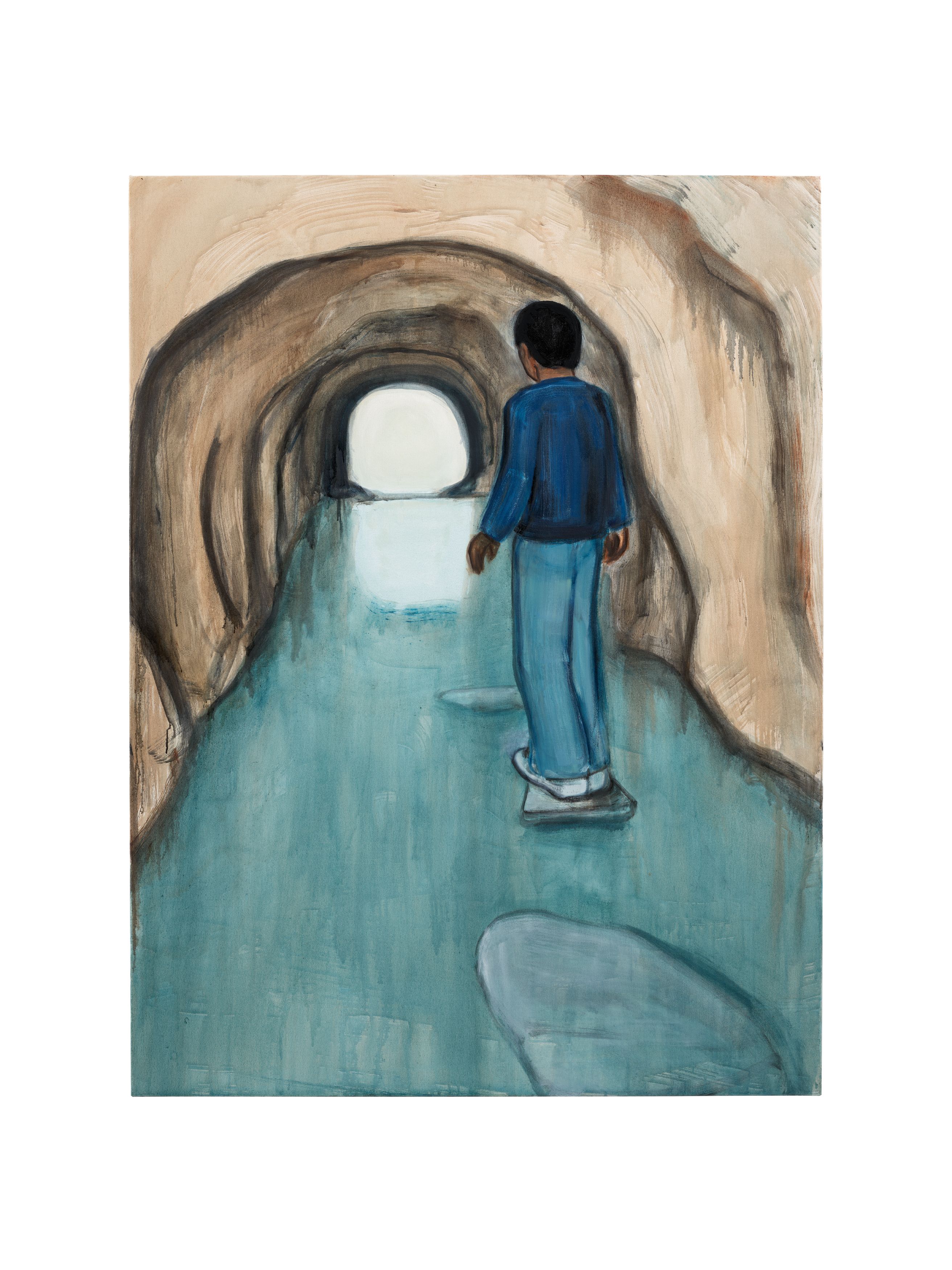

In Two Boys, Foliage, the banyan is densely packed, its dark green leaves painted in expressionistic brushstrokes that cascade in a zigzag across the canvas, mirroring the dizzying perspective of the boy perched at the very top as he looks down toward his companion. By contrast, in Lattice, Krishanu relegates leaves to a more minor position, with the branches here acting as a literal support for the boy seated deep in thought, recalling the playground structures of Krishanu’s earlier paintings. He exists, as all figures do in Krishanu’s paintings, in a world apart—one constructed through strokes and washes, layered with intent and experimentation. These are places that exist, drawn from the well of life, yet they do not share its plane.

All of this is possible, in Krishanu’s deft hands, through painting: its long history, its laborious processes, and, above all, its ability to convey sensation and assert presence in real, material terms. Bold in their palettes and stripped of extraneous detail, Krishanu’s paintings distill the fundamentals of the medium from a sizable repertoire of artistic referents—from ancient Buddhist frescoes in the Ajanta Caves, to the moody backgrounds of El Greco, the populist modernism of Amrita Sher-Gill, and the character studies of Alice Neel—all articulated in a voice distinctively his own.

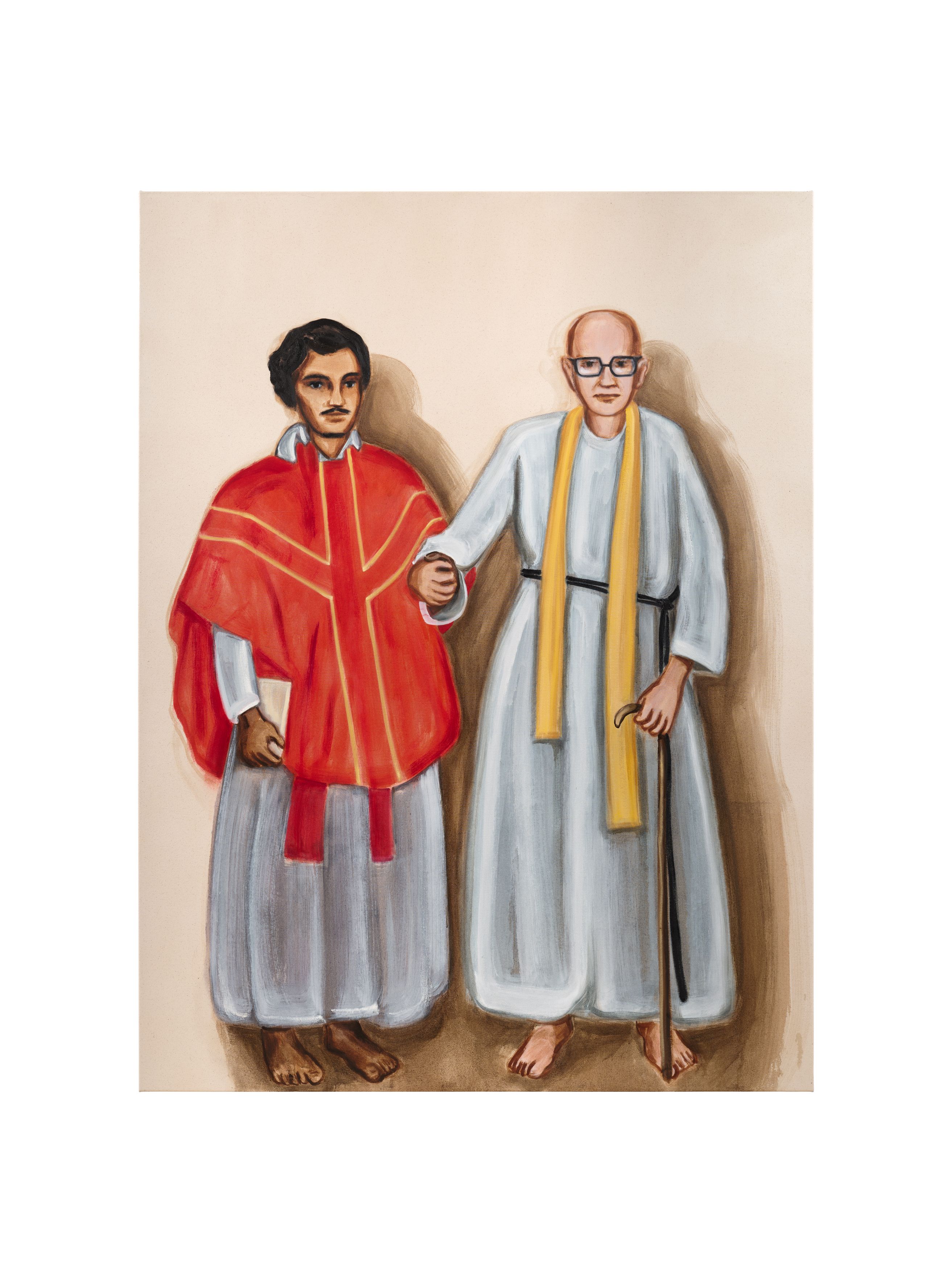

Born in England to a White Christian missionary father and an Indian-born theologian mother, Krishanu moved as an infant with his parents and older brother to Dhaka in 1981, where his father served as a priest in the Church of Bangladesh, established in 1974 in the wake of the country’s independence from Pakistan in 1971. Krishanu’s encounters with flesh-and-blood people, his childhood memories, and the surfeit of emotions tied to places—the Bangladesh of his youth, punctuated by trips to India and back to the UK—undergird and resurface in his paintings, often developed in series that continue for years. The ongoing series Another Country, begun in 2012, follows two young boys in various settings across India and Bangladesh, drawing inspiration from, without being beholden to, photographs of Krishanu and his brother. The rituals and institutions of Christianity are a recurring subject. The Mission series, also begun in 2012, depicts figures—some recalling the artist’s parents—within the processes of blessing, ordination, and preaching, while Holy Family focuses on portraits of brown-skinned bishops, nuns, and priests, deliberately countering the dominant depictions of White clergy and laity that pervade the Euro-American painting canon. There are traces of real people, real lives, yet these are mediated by canvas and brush—suspensions of oil and pigment, surfaces and supports.

The paintings that comprise the Mission and Holy Family series take religion as their subject, but they are not religious in the sense of being devotional or illustrative in any instrumental way. And despite the immediacy and directness of their pared-down compositions, they are not didactic works. Rather, these paintings are imbued with firsthand experiences of religion in a postcolonial context—experiences displaced at a critical remove, through painting. In this way, Krishanu resists the documentarian impulse that crowds so much of Western engagement with the subcontinent, a history marked by colonial imposition and assumptions of cultural superiority. His paintings forgo the mimetic replication of encounter for something more difficult to place, and all the more enthralling: a sense of being both within and without, a grasping toward feelings that words alone cannot articulate. Krishanu knows, however, that painting can achieve this through its ability to condense and set in motion the sensation of being transformed.

In Blessing (2024), Krishanu materializes tacit ambivalence within the context of Christian rites. The titular act is staged within a simple church interior, suggested by a set of pale orange columns. At center, a Brown bishop presides over the blessing of a man with black hair, his back turned to the viewer and a slash of red fabric draped across his white garments. Standing slightly above him are two White priests in profile, who lay their hands in solemn ceremony, pale against the black of his head. As in many of Krishanu’s Mission paintings, the focus of the scene is on the Brown members of the clergy and congregation—boys and women huddled together in the foreground. At the painting’s far left, three young robed men flanking the ceremony are shown in full view: two observe the ritual, while the central figure faces the viewer yet looks off into the distance. Within each canvas, Krishanu balances restraint and freedom, availing himself of the vast repertoire of painterly techniques, toggling between the generic and the particular, and probing the internal psychological struggles of individuals and the social structures that shape them.

None of these fonts of inspiration alone—not art history, nor group psychology, and certainly not religion—offers a full account of why painting remains so captivating, and why Krishanu’s paintings feel so exciting today. One might briefly point to his painting of a purple-walled chapel, Open Door (Chapel), 2024, its red roof bright against a blue sky, its cerulean doors open to reveal—though not unveil—a pitch black interior. And one might note that this work rhymes wonderfully with the 2022 painting Shrine (Candles and Christ), in which the open mouth of a cave is framed by a row of tapers in red, yellow, white, and green—the same colors of a tiny portrait of Christ at the top edge of the canvas. If it can feel superfluous to describe the formal intricacies of Krishanu’s paintings, it is because they are knowable from an unmistakable rush of sensation, like the most transformative acts of faith. Their immediacy, however, does not diminish the careful labor and control of Krishanu’s hand, which works deftly and with consideration for the audiences who encounter his work.

Press

ARTnews