Ahmed MorsiArt Basel OVR:20c

Emblematic Morsi paintings made between 1971 and 1996—showcasing his unique figurative style, characterized by their dream-like narratives and unconscious, fragmentary invocations of his Egyptian homeland.

Artwork

It has been said that Ahmed Morsi (born 1930) "paints his poetry and writes his paintings." With a seven-decade oeuvre that spans paintings and poetry composed in his birth city of Alexandria, Egypt in the late 1940s and 1950s to more recent works from his New York studio where he has resided since 1974, Ahmed Morsi is the most prominent living Egyptian artist of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. His work has been celebrated and collected throughout the Arab world by public institutions and preeminent private collectors.

Salon 94 presents emblematic Morsi paintings made between 1971 and 1996, showcasing his unique figurative style, characterized by their dream-like narratives and unconscious, fragmentary invocations of his Egyptian homeland.

While never part of an established artistic school, Morsi's work can be considered under the larger umbrella of global Surrealism—a revisionist category that looks beyond the narrow, Parisian-centric definition of surreal practices policed by avant-garde purists such as Andre Breton. Coming of age in the late colonial period in Alexandria where French, Italian, Greek, Armenian, and Syrian cultures thrived alongside the local inhabitants, Morsi had firsthand exposure to European avant-garde art that was regularly exhibited in the city's thriving cultural milieu. Morsi's early work was influenced by modernist masters such as Picasso, Brancusi, de Chirico, and Giacometti—and this early exposure to first generation Surrealism also transpired in his work as a translator and art critic. Morsi authored the first Arabic monograph of Picasso in 1969 and translated the surrealist writings of Paul Éluard and Louis Aragon into Arabic.

After leaving Alexandria for Baghdad and later Cairo, Morsi left the Middle East to immigrate to New York in 1974. While Morsi did show his paintings and continue to write poetry in America, his work was never fully recognized in his new homeland. Morsi's status as an exile was an important part of his identity, and even served as a muse for his painting and writing; as such, even when he exhibited in SoHo at the height of the 1980s art boom, the enthusiastic reception of his paintings quickly evaporated when Morsi refused to renounce his Egyptianness for a more assimilated identity. As the American art world was practically monocultural in the 80s, there was no space for an artist who constructed a practice in relationship to a faraway homeland; as such, Morsi remained hidden in plain sight in the center of Manhattan, working prolifically in his midtown studio under the cover of his exile status. Until now, with much of the art historical canon under revision, it has been challenging to appreciate this complex expatriated artist who uniquely synthesized Surrealism with his Middle Eastern visual and literary heritage. As Morsi has said of his decades in New York, a well-kept secret of his own making, "My work has always been here. I have always been here. Busy working."

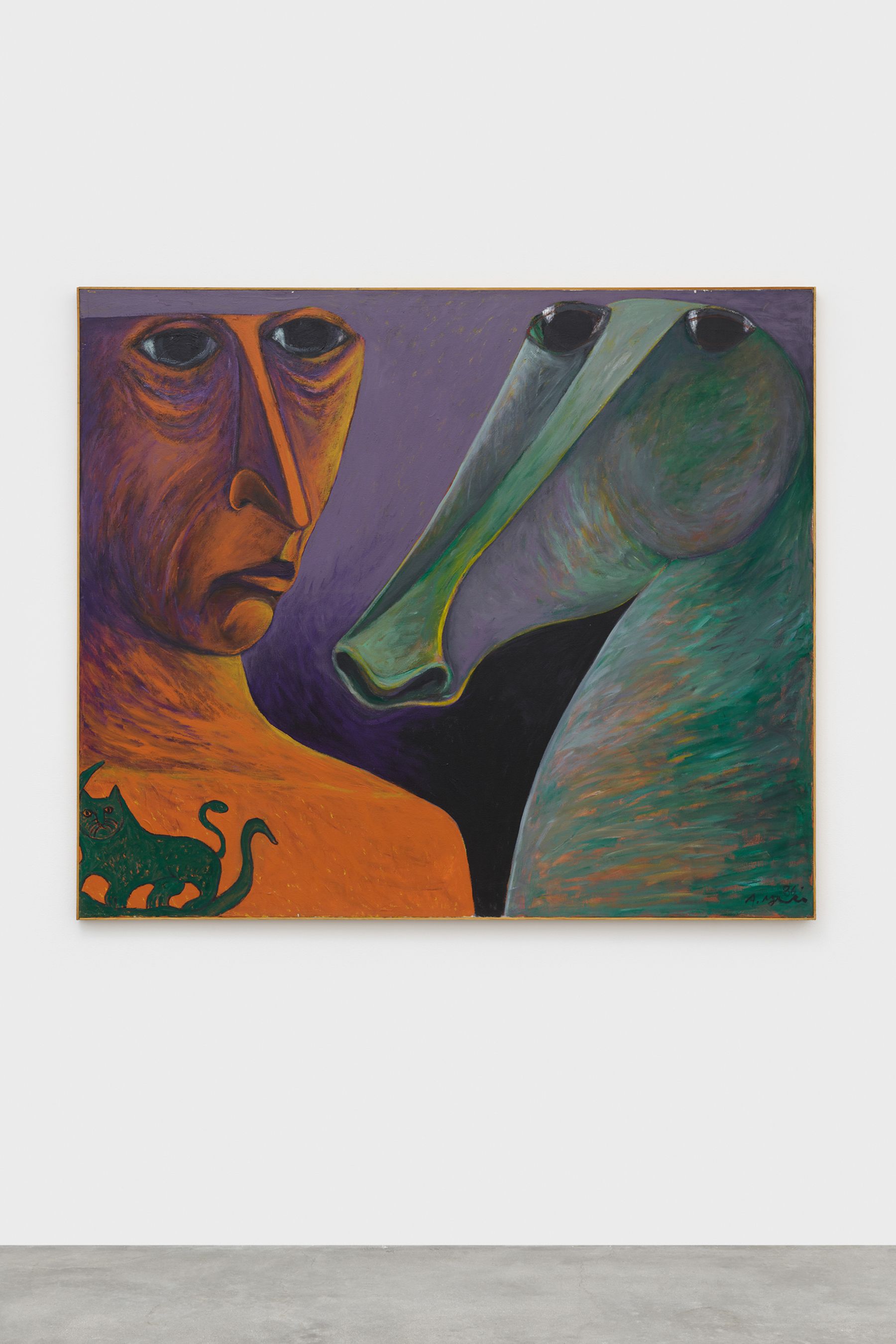

Morsi's unique language metabolism of Surrealism can be seen in works such as Walking the Bird (1971)—whose sister painting is part of the collection of the Museum of Egyptian Modern Art in Cairo—which is emblematic of Morsi's style and narrative preoccupations. Typifying Morsi's concerns are the theatrical architectural space and work's sun-drenched palette that evoke timeless, atmospheric memories of Alexandria. Figures in Morsi's work often appear to be androgynous and somewhat mythical creatures, oftentimes blending animal and human features such as in the untitled close-up, double portrait of a man and a horse. These empathetic human-animal depictions are heightened through Morsi's signature rendering of the figures' enlarged eyes as their most dominant feature. These mysterious eyes not only conjure the Egyptian mythological Eye of Horus—an ancient symbol of sacrifice, healing, and protection—but also evoke the primacy of visuality as the motor of his work as both a poet and painter. As Morsi has said, "images stored in the visual memory" are the well-source of his dual practice.

This presentation at Art Basel OVR prefigures Salon 94's forthcoming exhibition of Ahmed Morsi's work in Fall 2021.