Walton Ave & Friends

The exhibition traces Ahearn's and Torres' life cast sculptures of The South Bronx Hall of Fame (1979) and the Walton Avenue wall mural, Back to School (1985)

Installation Views

Artwork

Juanito, Walton Ave 1984 (c. 1991). Sculpture by John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres. Rappers: Anthony Buie and Kevin Green. Video produced by Charlie Ahearn and George Breidenbach. Sitter: Juanito

Juanito, Walton Ave 1984 (c. 1991)

(Produced by Charlie Ahearn and George Breidenbach, Sculpture by John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres, Rappers: Anthony Buie and Kevin Green, Sitter: Juanito)

Walton Ave & Friends

Walton Ave & Friends brings together sculpted portraits from across the oeuvres of John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres, beginning with The South Bronx Hall of Fame (1979), a suite of 21 singular busts produced at the alternative art space Fashion Moda, the site of the artists’ initial encounter. As founding director Joe Lewis wrote, “[Fashion Moda] was an outlet for the disenfranchised, a Salon des Refusés that cut across the uptown/downtown dichotomy, across the black/white/Hispanic isolation.” Their storefront castings quickly attracted a curious crowd of everyday Bronx residents: mothers and fathers running errands, children returning home from school, and patients from a nearby methadone clinic—ordinary people, unlike the war heroes, royalty, or the divine typically glorified in the pages of art history. The artists uplift their mostly Black and Latinx subjects by depicting them, through experimentation with form and an expansive range of skin tones, with nuance and contradiction. Unlike contemporaneous sculptors whose realism manifests as allegorical subjects like Liberty or Justice, or whose figures underscore ideas of power or beauty, the works of Ahearn and Torres undeniably express the distinctive identity and spirit of the subjects from which they are cast. Their deeply humanistic approach to portraiture is based in trust (the casting process is unpleasant and vulnerable) and is also reciprocal (each subject receives a painted sitter’s proof to keep). These proofs are a point of pride for those who choose to live with them and reaffirm the idea that all lives are worthy of representation. Indeed, receiving the cast portrait is often profoundly affective and satisfies the very real human yearning to see oneself reflected in the art of one’s time. The portraits of The South Bronx Hall of Fame are positioned high above the heads of visitors, beckoning all to behold them from below similarly to the original Fashion Moda installation, though set now within the magnificent limestone walls of an Upper East Side ballroom.

Ahearn and Torres brought the life casting process directly into the community: setting up on the sidewalk beyond the walls of Fashion Moda, they worked even deeper into the community of the Bronx along Walton Avenue. Their block-party-style happenings dissolved any idea of the genius studio artist working in isolation and were instead fixtures of the community they portrayed. In 1985, the artists installed their monumental Back to School as an immersive mise-en-scène overlooking Walton Avenue at 170th Street. The high relief sculptures, presented individually and in pairs, convey the rush of excitement of a child’s first day of school after summer break. The daughter-mother pair Maggie and Connie (the former a consistent subject of Ahearn’s over the years), depicts the prepubescent Maggie toting her baby doll—an idealized image of childrearing—at the same time that her real-life caretaker, herself pregnant, lugs heavy bags of groceries needed to feed her family. Underneath them, Ralph and Kido are spotted in warm embrace; brawny Ralph, the school building’s superintendent, joyfully welcomes Kido back to the classroom, a site of self-determination. The commotion doesn’t seem to affect Jay with Bike, who straddles his bicycle, lost in thought. The scene is closely watched by Titi in Window, cast from a neighborhood woman who, although she had no children of her own, carefully ensures the safe travels of the children in her community—a catcher in the rye. The frieze installation recalls a centuries-old tradition in Western art of picturing scenes of great battles and mythologies across horizontal bands crowning temples, palaces, and monuments. Ahearn and Torres similarly monumentalize their subjects, elevating the lives and labors of familiar people to a status of great significance and splendor.

For more information about John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres, please contact Nicolas Ochart.

When Worlds Collide by Joe Lewis

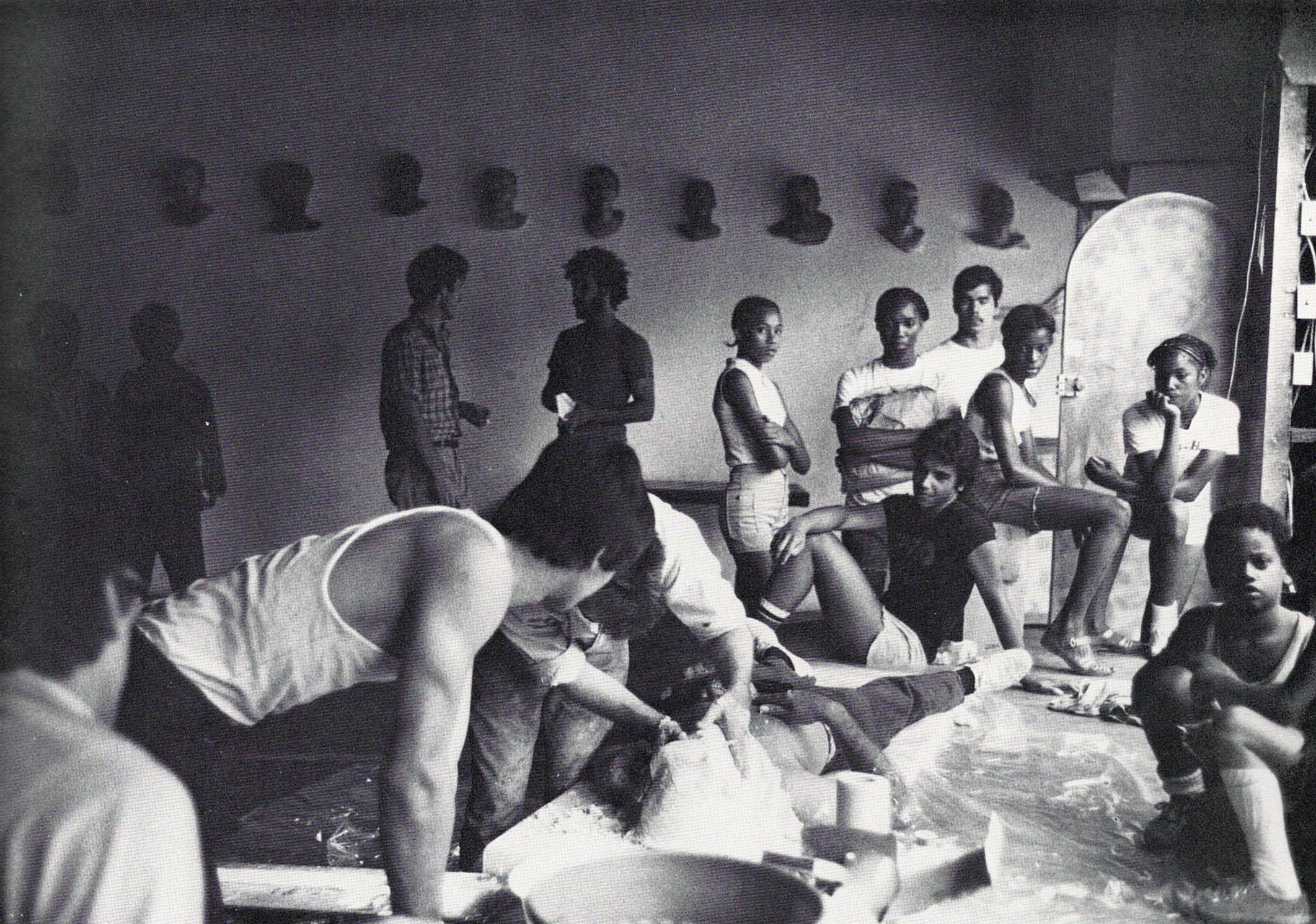

Torres [Left, in white undershirt] and Ahearn [center] during casting of Carlos, with Fashion Moads co-directors, Stefan Eins and Joe Lewis [standing background, left to right], Fashion Moda, July 1979

South Bronx Hall of Fame (1979)

John's journey into casting began when he stumbled upon a book on makeup for television and film in art maven Patti Astor's East Village apartment. Initially interested in creating horror movies, John made his first casts of artists in the downtown scene, including Bill Rice, Robin Winters, and his brother, Charlie Ahearn. However, John found the downtown community to be insular. At his brother's suggestion, he went to cast at Fashion Moda. In 1979, his seminal exhibition, The South Bronx Hall of Fame, included multiple life-cast portraits of local people. They were installed well above average height, with some looking off into the distance, some contemplative, and others directly engaging the viewer in the storefront's dimly lit, mismatched white walls. The exhibition was an enormous community hit, with people flooding the gallery to see their casts and show them to friends and family.

Ironically, John cast David Ortiz, Rigoberto's cousin, before meeting Rigoberto. While driving past the storefront, David and Rigoberto’s other cousin, Wally Ortiz, discovered Fashion Moda. They knew of Rigoberto's mold-making and casting experience working at his uncle's factory manufacturing religious figures. David urged him to meet John and check out the exhibition. John and Rigoberto quickly became friends.

John vividly remembers David as "high-octane," animated, exuberant, and friendly, always commanding attention. Their interaction led to an impromptu collaboration that pushed John in a new artistic direction. The result was the first wide-open mouth cast—a vibrantly colored and dynamic portrait with David's head confidently cocked to the side, exuding a sense of swagger and poise, his bright eyes focused upward and mouth ajar. Adorned in a stylish turned-up collared shirt, symbolizing hipness, slickness, and coolness, he was magnetic, drawing all the energy in the room.

John Ahearn, David Ortiz (Laughing), 1979

Other notable pieces attributed to John from The South Bronx Hall of Fame include Big City; his moniker was well-deserved. A gentle giant, he was one of the many visitors from the local methadone clinic who frequented the gallery. John captured the effects of Big City's drug addiction through translucent grey shadows overlaying the subject's milk-chocolate complexion. Pregnant Girl showcases a relaxed, trusting facial expression; her ghostlike pallor and straightforward gaze are captivating and reveal the inner glow of gestation. Shirley, attributed to Rigoberto, foreshadows his quest for an unblemished representation of nature. The works’ cool, calm, collected skin tones are like a whole rest in a symphonic concert.

John's approach to casting was unpretentious. He took Polaroids of potential sitters, using them as inspiration to paint the pieces, cast them, took them home, and brought them back to the gallery. Much later on, using the same process, John cast me. He laid me down on my back, placed two short straws in my nose so I could breathe, and then poured some gunk over my face and shoulders. It was the same stuff dentists use to take impressions of your teeth. He covered that with the same plaster-soaked cloth used for broken bones to create a shell. The experience was jarring and humbling, and required much trust.

A critic of commodification, John made a second cast for most sitters, making friends with them; some have lasted until today. John lacked formal training and his artistic process contrasted with the neo-expressionist movement of the 1970s and 80s. Rather than simply painting, he poured his emotions and responses into creating a direct connection between the viewer and the artwork. This approach represented a bold departure from the conventions of realism, inviting the audience to engage with art on a deeper and more personal level.

Conversely, Rigoberto's artistic path, shaped by realism, diverged from contemporary art’s mainstream and was influenced by his employment at his Uncle Raul's religious artifact factory. Devotional items, with their divine purpose, demand accuracy, detail, and flawlessness. Rigoberto's rejection of idealization and embrace of direct observation exemplifies his process, and the dynamism of contemporary art also influenced it.

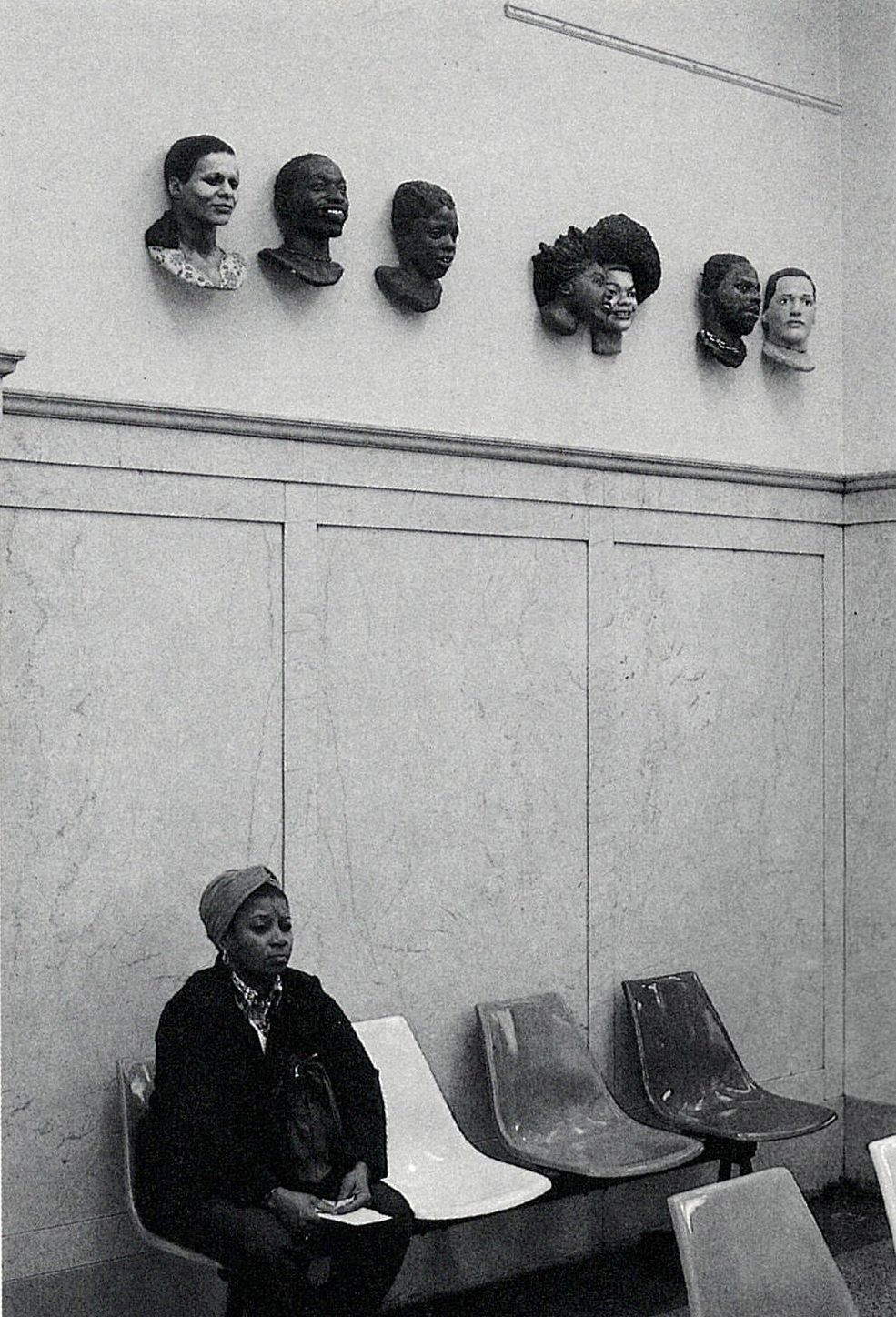

Installation of Fashion Moda heads at Con Edison waiting room, Bronx, November 1979.

Shortly after The South Bronx Hall of Fame closed, several works were displayed at the local Con Edison payment office and then at the Times Square Show, which The Village Voice called "The First Radical Art Show of the '80s." The exhibition responded to the formalist New York art scene that needed more space for young artists, new ideas, women, and people of color. Colab, a politically engaged group of artists with an open membership of which John was a founding member, organized the show. Subsequently, The South Bronx Hall of Fame’s 1991–92 international tour began at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston, TX, and ended at the Contemporary Museum in Honolulu, HI. It was revived twenty years later in 2012 at Frieze Projects in New York, curated by Cecilia Alemani.

Walton Avenue (1985)

Walton Avenue block party inaugration of Back to School mural, 1985.

The artists' fourth significant public Bronx mural, Back to School (1985), was located on Walton Avenue at 170th Street, across from P.S. 64. This work differed in many ways from the artists' other wall works in size and storytelling. John described it as a labor of love without financial backing or insurance. The cast fiberglass figures on the building's facade told a complex story about the first day of school. The ever-watchful Titi sat in the window, representing the all-seeing, all-knowing observer in every neighborhood. The wall was parallel to the 170th Street IRT Jerome Avenue Line, and zoning conditions restricted the height of commercial buildings next to above-grade train stations to one story, making the mural visually accessible from many angles. Unfortunately, a fire damaged the piece. Still, Titi survived and was repaired, and appears in this exhibition with later versions of several other mural figures.

This work is powerful for its relatable normalcy, depicting familiar scenes across the nation, in big and small cities, urban or rural areas, among the wealthy and the less privileged: a mother returning home with her daughter after shopping, a smiling child carrying books, and a kid contemplating the future from their bike. This work challenges fictional narratives and myths about underserved communities and celebrates humanity using a visual language that contests established Western ideals of beauty, class, and race. One could replace any of the figures with a different group of people and still convey the same message: we are not so different from each other; we all have the same desires, needs, and dreams.

The Walton Avenue interventions, The South Bronx Hall of Fame, the murals, and the individual portraits are faithful and pathbreaking. Their projects developed organically, without the imposition of early social practices that follow the dictate "I know what's good for you." Their inclusive approach brought communities closer, creating new histories, inspiring self-worth, and reshaping the civic landscape.

Joe Lewis is an artist, writer, professor of art at the University of California, Irvine, and founding director of the South Bronx art space Fashion Moda.

Press

Animal

Artforum

The New York Times